Wernig Laboratory

October 9, 2024: Welcome new postdoc Kirill to the lab!

Sep 17, 2024: Jinzhao's paper accepted in principle!

Jul 11, 2024: Gernot's paper published in Nature Communications!

March 21, 2024: Marius Mader's paper comes out in Nature Neuroscience!

Oct 10, 2023: Yongjin receives the Sammy Kuo Award from the Neuroscience Institute - CONGRATULATIONS!

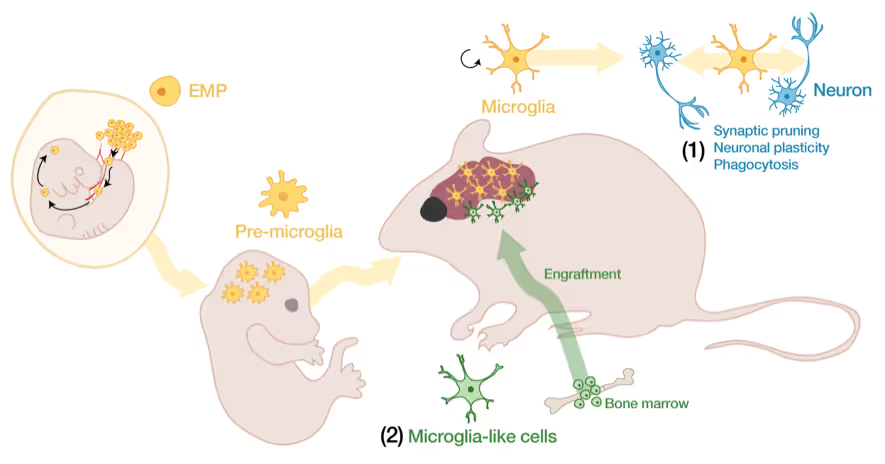

Yongjin's paper on cell therapy in a mouse AD model is published in Cell Stem Cells

Our lab is generally interested in the molecular mechanisms that determine cell fates

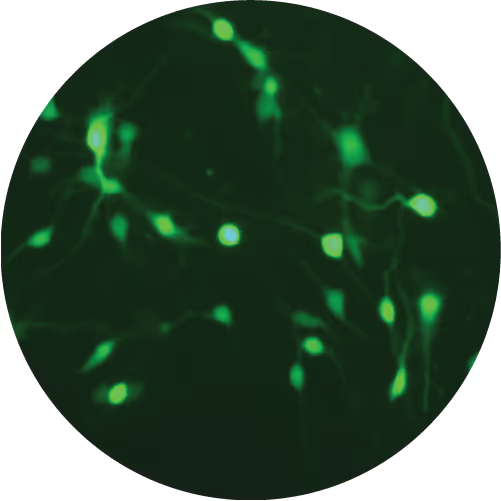

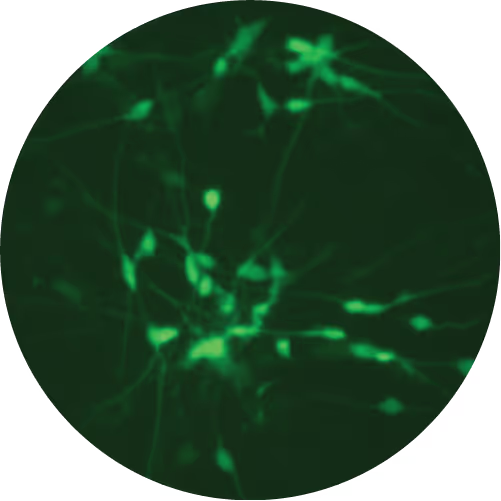

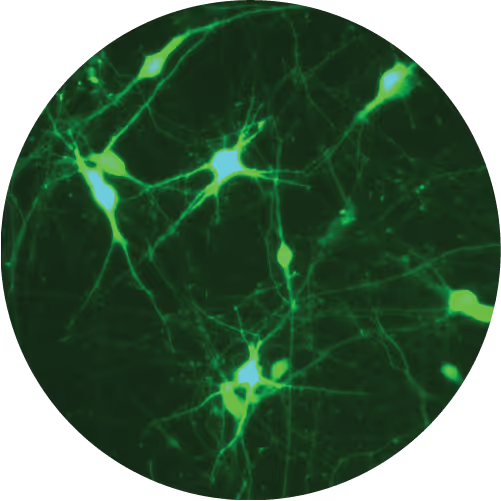

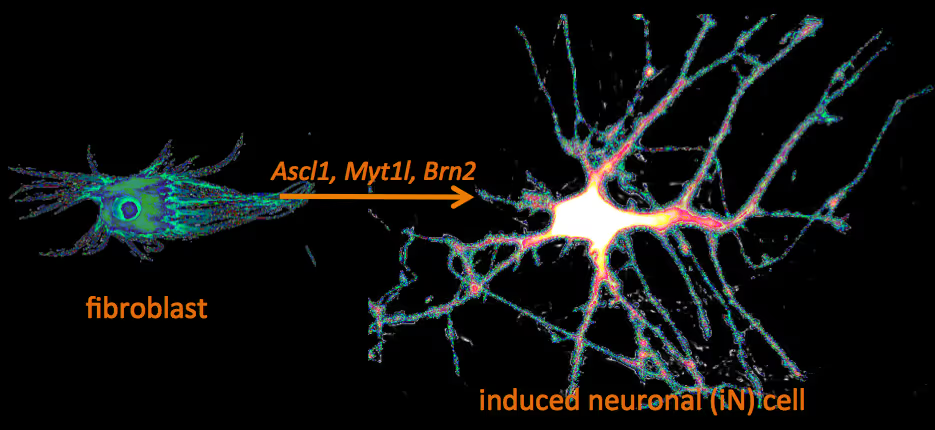

Recently, we have identified a pool of transcription factors that are sufficient to convert skin fibroblasts directly into functional neuronal cells that we termed induced neuronal (iN) cells. This was a surprising finding and indicated that direct lineage reprogramming may be applicable to many somatic cell types and many different directions. Indeed, following our work others have identified transcription factors that could induce cardiomyocytes, blood progenitors, and hepatocytes from fibroblasts.

We are now focussing on two major aspects of iN and iPS cell reprogramming:

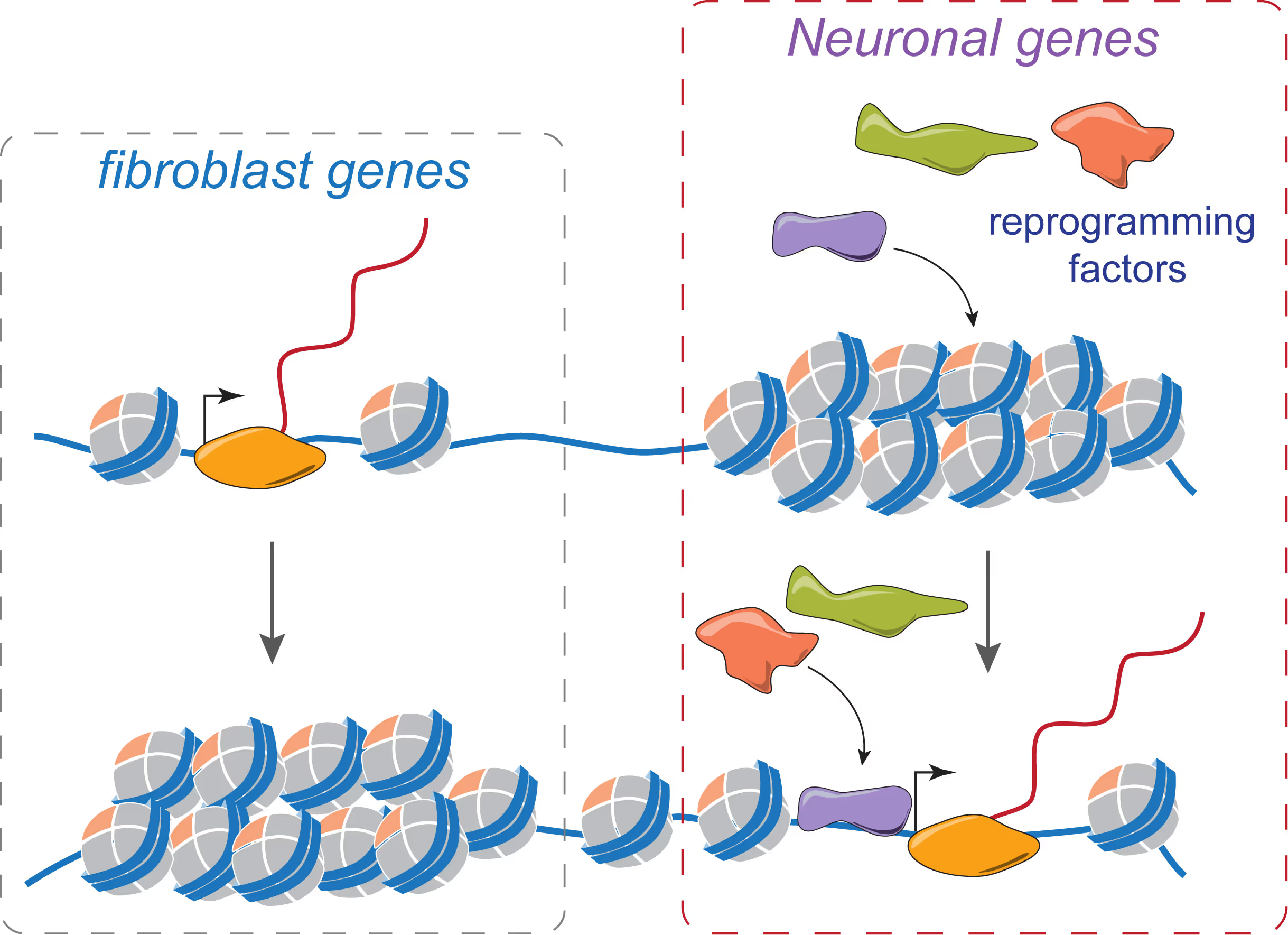

(i) we are fascinated by the puzzle how a hand full of transcription factors can so efficiently reprogram the entire epigenome of a cell so that it changes identity. To that end we are applying genome-wide expression analysis, chromatin immunoprecipitation, protein biochemistry, proteomics and functional screens.

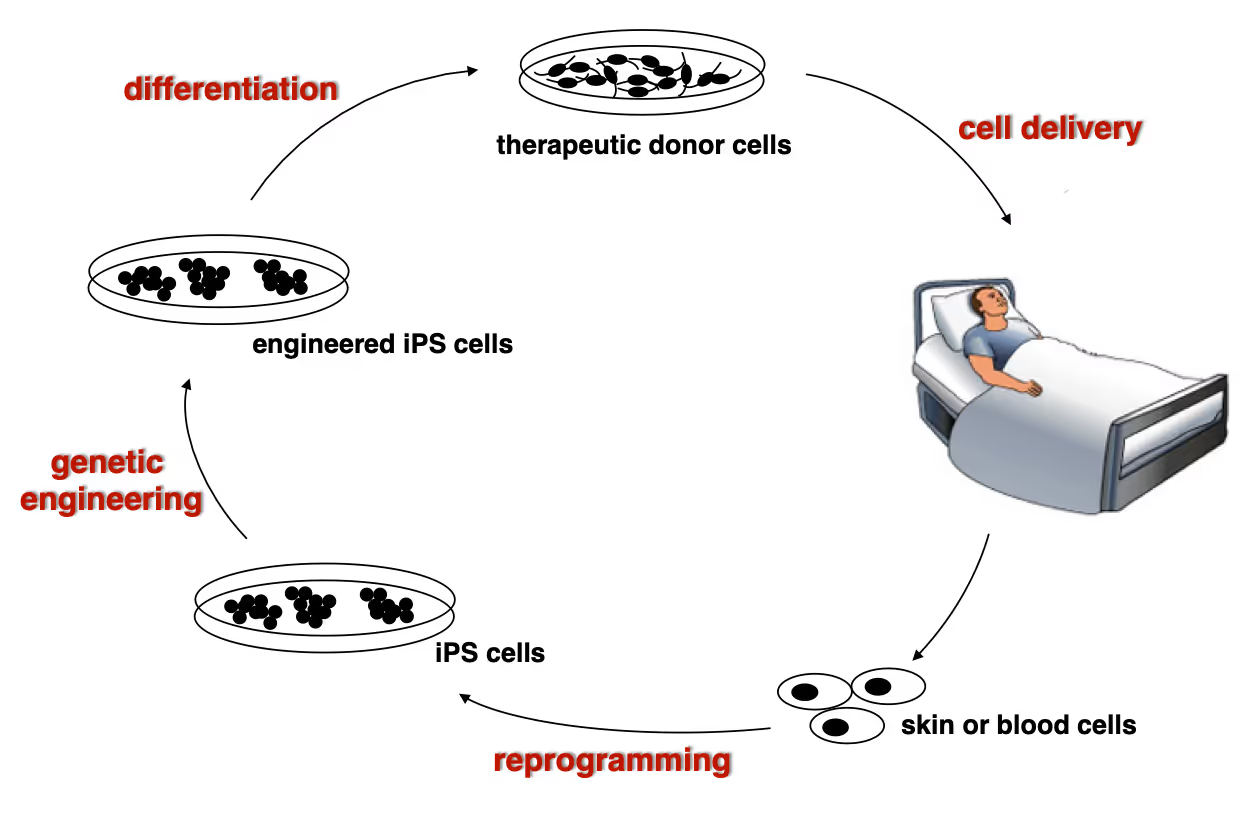

(ii) it is equally exciting to now use reprogramming methods as tools to study or treat certain diseases. iPS cells have the great advantage that they can easily be genetically manipulated rendering them ideal for treating monogenetic disorders when combined with cell transplantation-based therapies. In particular we are working on Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa in collaboration with Stanford's Dermatology Department. An exciting application of iN cell technology will be to try modeling neurological diseases in vitro. We perform both mouse and human experiments hoping to identify quantifiable phenotypes correlated with genotype and in a second step evaluate whether this assay could be used to discover novel drugs improve the disease progression.

Wernig Lab Research

Overview

Our lab is interested in the molecular mechanisms that define neural lineage identity focusing on transcription factors and chromatin biology. We use cellular reprogramming to understand how neurons are induced, how they mature and maintain their identity. Reprogramming also allows us to generate a novel tool box to study human neuronal and glial cell biology which become powerful human disease models in combination with genetic engineering. We further seek to develop reprogramming & genetic engineering approaches towards stem cell-based therapies. Finally, we study microglia-neuron interactions with the ultimate goal to understand the brain's immune system in health and disease and to exploit microglia for therapeutic and regenerative purposes.

Human neuronal cell disease modeling

Neurosychiatric diseases like autism and schizophrenia are highly complex brain disorders difficult to model in mice in part due to complex genetic etiology and sometimes affecting human-specific genes. We develop novel human cell models to investigate disease-relevant cell biological phenomena.

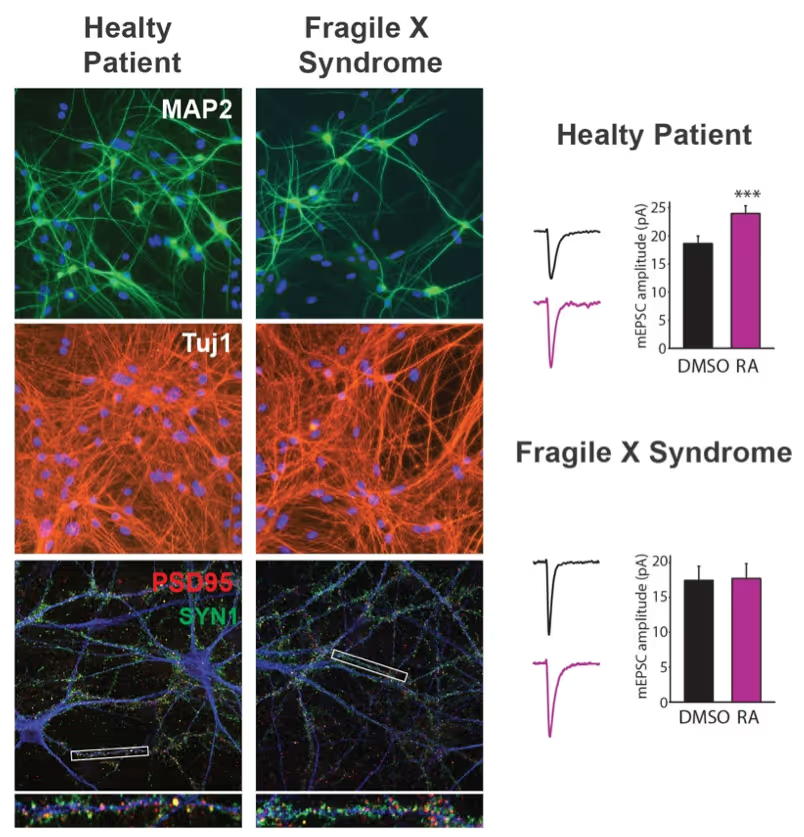

Generation of defined human neuronal cell types to study neuronal cell biology

We have and continue to develop protocols to generate specific types of neurons such as pure glutamatergic and pure GABAergic neurons from human pluripotent stem cells using transcription factors. In combination with genetic engineering or deriving iPS cells from patients, we then interrogate the cell biology of human neurons that carry disease-causing mutations. A particular focus is on synaptic function as shown in the figure on the right on Fragile X Syndrome neurons in collaboration with Lu Chen and Tom Südhof's laboratories.

Making neurons from blood

The ability to generate functional induced neuronal cells from distantly related somatic cell types is fascinating but also offers the opportunity to obtain neurons from a larger cohort of human subjects. In particular blood is readily available and we showed can be efficiently converted into functional neurons from young and aged donors.

Developing next generation cell therapies

The combination of reprogramming and gene editing is truly powerful as it provides exciting new possibilities to generate cells that can be transplanted and have disease modifying activity. We currently apply this approach to restore mono-genetic diseases, but our vision goes beyond simple regenerative medicine. We will be able to genetically engineer designer cells that functionally integrate into diseased tissue equipped with sensing and intelligent disease-response mechanisms.

Towards a Phase 1 clinical trial for the fatal skin disease Epidermolysis Bullosa

Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa is a severe, blistering monogenetic skin disease caused by mutations in the gene coding for type VII collagen. We have developed a 1-step gene editing/iPS cell reprogramming method to rapidly generate patient iPS cells corrected for their disease-causing mutations in the Collagen7a1 gene. In collaboration with dermatologist Tony Oro we are developing a cell manufacturing process compatible with Good Manufacturing Procedures (GMP) to obtain FDA-approval for a first in man Phase I clinical trial with with a genetically engineered iPS cell product.

Exploiting glia cell transplantation to treat neurodegenerative disease

Both oligodendrocyte precursor cells as well as microglia can efficiently repopulate the brain. We are interested in exploiting the properties of these cells to develop novel cell therapies for the brain either to use the transplanted cells to restore function such as myelination, to alter the function of transplanted cells for therepeutic benefit, to use the cells as vehicles for therapeutic molecules, or ultimately to develop designer cells that are engineered with genetic synthetic biology circuits to sense and interfere with disease processes of the brain.

Mechanisms of neural cell lineage identity

We are interested in the molecular mechanisms that define neuronal and glial cell identity. We found sets of transcription factors that can convert fibroblasts or lymphocytes into neurons and oligodendrocytes. These factors are also operational during normal development and are largely responsible to induce terminal lineages from progenitor cells.

"On target" pioneer factors and chromatin remodeling during neuronal induction

We found that Ascl1, one of our reprogramming factors, has a unique ability to access its physiological targets even in fibroblasts where these sites are in a closed chromatin configuration. We are fascinated by this "on target" pioneering property and are investigating how Ascl1 can access its target sites in an unfavorable chromatin environment and how it then remodels the chromatin at these sites to activate the neuronal transcriptional program.

Maintenance of neuronal identity

Once neurons are made, there ought to be also mechanisms that maintain neuronal identity. We stumbled upon a novel repressive mechanism: The neuronal-specific transcription factor Myt1l continuosly represses many non-neuronal programs in neurons leaving the neuronal program open to activate by other factors and thereby ensuring stable neuronal gene expression. Myt1l was also recently found to be mutated in autism and schizophrenia.

Microglia-neuron interactions in the healthy and diseased brain

Microglia, the brain's resident immune cells, are fascinating cells. They are derived from yolk sac progenitor cells early during development, are long-lived, and are not exchanged from bone marrow progenitor cells under physiological conditions. Microglia have been implicated in synaptic pruning, adult neurogenesis, and various brain diseases including Alzheimer's disease and Schizophrenia.

Developing an efficient microglia replacement system

We have developed a method to efficiently replace endogenous microglia from circulating cells without genetic manipulation. This does not happen physiologically but under certain conditions peripheral blood cells cross the blood-brain-barrier, migrate into the brain parenchyma and replace endogenous cells. We are investigating the cellular and molecular signals that enable circulating cells to invade the brain in order to further improve microglia replacement strategies.

The role of microglia in the normal and the diseased brain

Our ability to replace microglia provides us with a powerful tool to functionally perturb microglia function in normal and disease states. E.g. the microglial gene TREM2 is a strong Alzheimer's disease risk gene, but major questions about the neuro-immune interplay in the context of neurodegeneration and aging remain unsolved. Microglia replacement also provides an exciting prospect to develop novel cell therapies for a variety of brain diseases including enzyme deficiency syndromes, neurodegeneration, and brain tumors.

Lab Gene Expression Data

Publications

BAI1, BAI2, and BAI3 (for 'Brain-specific Angiogenesis Inhibitor-1, -2, and -3') are adhesion-GPCRs implicated in neuronal development. The precise roles of individual BAIs remain unclear. BAIs interact with two sets of ligands, secreted C1ql proteins and membrane-bound RTN4R proteins (a.k.a. NoGo receptors), but which of these ligands regulate specific functions of BAIs is incompletely understood. To address these key questions, we here systematically examine the functions of the three BAIs in neuronal development using hippocampal neuron-glia cultures, genetic knockouts, and rescue experiments. In a direct comparison, we demonstrate that deletions of BAI1 or BAI3, but not of BAI2, increase axonal and dendritic arborizations but decrease excitatory synapse formation, while inhibitory synapse formation remains unaffected. Since biochemical and cellular assays reveal that only BAI3 binds to both RTN4Rs and C1qls, we analyzed the role of these two ligands in controlling BAI3 functions using rescue experiments. We find that RTN4R-binding to BAI3 is essential for restricting axonal and dendritic arborizations and for enabling excitatory synapse formation, whereas C1ql-binding to BAI3 is only required for synapse organization as monitored in hippocampal neuron-glia cultures. Thus, BAI1 and BAI3 perform diverse functions that shape multiple facets of neuronal development and that require their interaction with RTN4Rs.

BAI1, BAI2, and BAI3 (for 'Brain-specific Angiogenesis Inhibitor-1, -2, and -3') are adhesion-GPCRs implicated in neuronal development. The precise roles of individual BAIs remain unclear. BAIs interact with two sets of ligands, secreted C1ql proteins and membrane-bound RTN4R proteins (a.k.a. NoGo receptors), but which of these ligands regulate specific functions of BAIs is incompletely understood. To address these key questions, we here systematically examine the functions of the three BAIs in neuronal development using hippocampal neuron-glia cultures, genetic knockouts, and rescue experiments. In a direct comparison, we demonstrate that deletions of BAI1 or BAI3, but not of BAI2, increase axonal and dendritic arborizations but decrease excitatory synapse formation, while inhibitory synapse formation remains unaffected. Since biochemical and cellular assays reveal that only BAI3 binds to both RTN4Rs and C1qls, we analyzed the role of these two ligands in controlling BAI3 functions using rescue experiments. We find that RTN4R-binding to BAI3 is essential for restricting axonal and dendritic arborizations and for enabling excitatory synapse formation, whereas C1ql-binding to BAI3 is only required for synapse organization as monitored in hippocampal neuron-glia cultures. Thus, BAI1 and BAI3 perform diverse functions that shape multiple facets of neuronal development and that require their interaction with RTN4Rs.

Marius Marc-Daniel Mader, Alexa Scavetti, Yongjin Yoo, Aaron Tianyue Chai, Takeshi Uenaka, Marius Wernig

Migration of transplanted allogeneic myeloid cells into the brain following systemic haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell transplantation (HCT) holds great promise as a therapeutic modality to correct genetic deficiencies in the brain such as lysosomal storage diseases1-3. However, the toxic myeloablation required for allogeneic HCT can cause serious, life-threatening side effects, limiting its applicability. Moreover, transplanted allogeneic myeloid cells are highly vulnerable to rejection even in an immune-privileged organ like the brain. Here we report a brain-restricted, high-efficiency microglia replacement approach without myeloablative preconditioning. Contrary to previous assumptions, we found that haematopoietic stem cells are not required to repopulate the myeloid compartment of the brain environment, and Sca1- committed progenitor cells were highly efficient in replacing microglia following intracerebral injection. This finding enabled the development of brain-restricted preconditioning and avoided long-term peripheral engraftment, thus eliminating complications such as graft-versus-host disease. Evaluating its therapeutic potential, we found that our allogeneic microglia replacement method rescued the mouse model of Sandhoff disease, a lysosomal storage disease caused by hexosaminidase B deficiency. In support of the translational relevance of this approach, we discovered that human embryonic stem cell-derived myeloid progenitor cells display a similar engraftment potential following brain-restricted conditioning. Our results overcome current limitations of conventional HCT and may pave the way for the development of allogeneic microglial cell therapies for the brain.

Migration of transplanted allogeneic myeloid cells into the brain following systemic haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell transplantation (HCT) holds great promise as a therapeutic modality to correct genetic deficiencies in the brain such as lysosomal storage diseases1-3. However, the toxic myeloablation required for allogeneic HCT can cause serious, life-threatening side effects, limiting its applicability. Moreover, transplanted allogeneic myeloid cells are highly vulnerable to rejection even in an immune-privileged organ like the brain. Here we report a brain-restricted, high-efficiency microglia replacement approach without myeloablative preconditioning. Contrary to previous assumptions, we found that haematopoietic stem cells are not required to repopulate the myeloid compartment of the brain environment, and Sca1- committed progenitor cells were highly efficient in replacing microglia following intracerebral injection. This finding enabled the development of brain-restricted preconditioning and avoided long-term peripheral engraftment, thus eliminating complications such as graft-versus-host disease. Evaluating its therapeutic potential, we found that our allogeneic microglia replacement method rescued the mouse model of Sandhoff disease, a lysosomal storage disease caused by hexosaminidase B deficiency. In support of the translational relevance of this approach, we discovered that human embryonic stem cell-derived myeloid progenitor cells display a similar engraftment potential following brain-restricted conditioning. Our results overcome current limitations of conventional HCT and may pave the way for the development of allogeneic microglial cell therapies for the brain.

Yi Miao, Haoqing Wang, Kevin M Jude, Jie Wang, Jinzhao Wang, Marius Wernig, Thomas C Südhof

The adhesion-GPCR Brain-specific Angiogenesis Inhibitor-3 (BAI3) plays a crucial role in organizing synapses in the brain. However, how BAI3 engages one of its ligands, the C1q-like proteins (C1qls), remains largely unexplored. Here, we present the single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the C1ql3-BAI3 complex at 2.8 Å resolution. The structure reveals a hexameric configuration, where C1ql3 forms a central homotrimer that effectively captures three BAI3 molecules. These BAI3 molecules fit snugly into the grooves between the trimeric C1q domains of the C1qls, employing calcium ion (Ca2+)-mediated interactions that differ from previously characterized structures of C1q-like domain-mediated complexes. Furthermore, we conducted mutant analysis and cell surface staining, which confirmed the essential contact residues involved in this interaction. This unique binding mechanism not only enhances our understanding of the C1ql-BAI3-mediated synaptic organization but also sheds light on the functional dynamics of BAI3 in the brain.

The adhesion-GPCR Brain-specific Angiogenesis Inhibitor-3 (BAI3) plays a crucial role in organizing synapses in the brain. However, how BAI3 engages one of its ligands, the C1q-like proteins (C1qls), remains largely unexplored. Here, we present the single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the C1ql3-BAI3 complex at 2.8 Å resolution. The structure reveals a hexameric configuration, where C1ql3 forms a central homotrimer that effectively captures three BAI3 molecules. These BAI3 molecules fit snugly into the grooves between the trimeric C1q domains of the C1qls, employing calcium ion (Ca2+)-mediated interactions that differ from previously characterized structures of C1q-like domain-mediated complexes. Furthermore, we conducted mutant analysis and cell surface staining, which confirmed the essential contact residues involved in this interaction. This unique binding mechanism not only enhances our understanding of the C1ql-BAI3-mediated synaptic organization but also sheds light on the functional dynamics of BAI3 in the brain.

Ching-Chieh Chou, Ryan Vest, Miguel A Prado, Joshua Wilson-Grady, Joao A Paulo, Yohei Shibuya, Patricia Moran-Losada, Ting-Ting Lee, Jian Luo, Steven P Gygi, Jeffery W Kelly, Daniel Finley, Marius Wernig, Tony Wyss-Coray, Judith Frydman

Ageing is the most prominent risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (AD). However, the cellular mechanisms linking neuronal proteostasis decline to the characteristic aberrant protein deposits in the brains of patients with AD remain elusive. Here we develop transdifferentiated neurons (tNeurons) from human dermal fibroblasts as a neuronal model that retains ageing hallmarks and exhibits AD-linked vulnerabilities. Remarkably, AD tNeurons accumulate proteotoxic deposits, including phospho-tau and amyloid β, resembling those in APP mouse brains and the brains of patients with AD. Quantitative tNeuron proteomics identify ageing- and AD-linked deficits in proteostasis and organelle homeostasis, most notably in endosome-lysosomal components. Lysosomal deficits in aged tNeurons, including constitutive lysosomal damage and ESCRT-mediated lysosomal repair defects, are exacerbated in AD tNeurons and linked to inflammatory cytokine secretion and cell death. Providing support for the centrality of lysosomal deficits in AD, compounds ameliorating lysosomal function reduce amyloid β deposits and cytokine secretion. Thus, the tNeuron model system reveals impaired lysosomal homeostasis as an early event of ageing and AD.

Ageing is the most prominent risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (AD). However, the cellular mechanisms linking neuronal proteostasis decline to the characteristic aberrant protein deposits in the brains of patients with AD remain elusive. Here we develop transdifferentiated neurons (tNeurons) from human dermal fibroblasts as a neuronal model that retains ageing hallmarks and exhibits AD-linked vulnerabilities. Remarkably, AD tNeurons accumulate proteotoxic deposits, including phospho-tau and amyloid β, resembling those in APP mouse brains and the brains of patients with AD. Quantitative tNeuron proteomics identify ageing- and AD-linked deficits in proteostasis and organelle homeostasis, most notably in endosome-lysosomal components. Lysosomal deficits in aged tNeurons, including constitutive lysosomal damage and ESCRT-mediated lysosomal repair defects, are exacerbated in AD tNeurons and linked to inflammatory cytokine secretion and cell death. Providing support for the centrality of lysosomal deficits in AD, compounds ameliorating lysosomal function reduce amyloid β deposits and cytokine secretion. Thus, the tNeuron model system reveals impaired lysosomal homeostasis as an early event of ageing and AD.

Jinzhao Wang, Thomas Sudhof, Marius Wernig

Neuroligins are postsynaptic cell-adhesion molecules that regulate synaptic function with a remarkable isoform specificity. Although Nlgn1 and Nlgn2 are highly homologous and biochemically interact with the same extra- and intracellular proteins, Nlgn1 selectively functions in excitatory synapses whereas Nlgn2 functions in inhibitory synapses. How this excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) specificity arises is unknown. Using a comprehensive structure-function analysis, we here expressed wild-type and mutant neuroligins in functional rescue experiments in cultured hippocampal neurons lacking all endogenous neuroligins. Electrophysiology confirmed that Nlgn1 and Nlgn2 selectively restored excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission, respectively, in neuroligin-deficient neurons, aligned with their synaptic localizations. Chimeric Nlgn1-Nlgn2 constructs reveal that the extracellular neuroligin domains confer synapse specificity, whereas their intracellular sequences are exchangeable. However, the cytoplasmic sequences of Nlgn2, including its Gephyrin-binding motif that is identically present in the Nlgn1, is essential for its synaptic function whereas they are dispensable for Nlgn1. These results demonstrate that although the excitatory vs. inhibitory synapse specificity of Nlgn1 and Nlgn2 are both determined by their extracellular sequences, these neuroligins enable normal synaptic connections via distinct intracellular mechanisms.

Neuroligins are postsynaptic cell-adhesion molecules that regulate synaptic function with a remarkable isoform specificity. Although Nlgn1 and Nlgn2 are highly homologous and biochemically interact with the same extra- and intracellular proteins, Nlgn1 selectively functions in excitatory synapses whereas Nlgn2 functions in inhibitory synapses. How this excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) specificity arises is unknown. Using a comprehensive structure-function analysis, we here expressed wild-type and mutant neuroligins in functional rescue experiments in cultured hippocampal neurons lacking all endogenous neuroligins. Electrophysiology confirmed that Nlgn1 and Nlgn2 selectively restored excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission, respectively, in neuroligin-deficient neurons, aligned with their synaptic localizations. Chimeric Nlgn1-Nlgn2 constructs reveal that the extracellular neuroligin domains confer synapse specificity, whereas their intracellular sequences are exchangeable. However, the cytoplasmic sequences of Nlgn2, including its Gephyrin-binding motif that is identically present in the Nlgn1, is essential for its synaptic function whereas they are dispensable for Nlgn1. These results demonstrate that although the excitatory vs. inhibitory synapse specificity of Nlgn1 and Nlgn2 are both determined by their extracellular sequences, these neuroligins enable normal synaptic connections via distinct intracellular mechanisms.

Takeshi Uenaka, Sascha Jung, Ishan Kumar, Kit Vodehnal, Mohit Rastogi, Yongjin Yoo, Mark Koontz, Christian Thome, Wanhua Li, Tamara Chan, Erin M Green, Kirill Chesnov, Zijun Sun, Shuyuan Zhang, Jinzhao Wang, Anthony Venida, Anne-Laure Mahul Mellier, Micaiah Atkins, Meredith Jackrel, Jan M Skotheim, Tony Wyss-Coray, Monther Abu-Remaileh, Hilal A Lashuel, Michael C Bassik, Thomas C Südhof, Antonio Del Sol, Erik Ullian, Marius Wernig

Microglia are the immune cells of the central nervous system and are thought to be key players in both physiological and disease conditions. Several microglial features are poorly conserved between mice and human, such as the function of the neurodegeneration-associated immune receptor Trem2. Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived microglia offer a powerful opportunity to generate and study human microglia. However, human iPSC-derived microglia often exhibit activated phenotypes in vitro, and assessing their impact on other brain cell types remains challenging due to limitations in current co-culture systems. Here, we developed fully defined brain microtissues, composed of human iPSC-derived neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, co-cultured in 2D or 3D formats. Our microtissues are stable and self-sufficient over time, requiring no exogenous cytokines or growth factors. All three cell types exhibit morphologies characteristic of their in vivo environment and show functional properties. Co-cultured microglia develop more homeostatic phenotypes compared to microglia exposed to exogenous cytokines. Hence, these tri-cultures provide a unique approach to investigate cell-cell interactions between brain cell types. We found that astrocytes and not neurons are sufficient for microglial survival and maturation, and that astrocyte-derived M-CSF is essential for microglial survival. Single-cell and single-nucleus RNA sequencing analyses nominated a network of reciprocal communication between cell types. Brain microtissues faithfully recapitulated pathogenic α-synuclein seeding and aggregation, suggesting their usefulness as human cell models to study not only normal but also pathological cell biological processes.

Microglia are the immune cells of the central nervous system and are thought to be key players in both physiological and disease conditions. Several microglial features are poorly conserved between mice and human, such as the function of the neurodegeneration-associated immune receptor Trem2. Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived microglia offer a powerful opportunity to generate and study human microglia. However, human iPSC-derived microglia often exhibit activated phenotypes in vitro, and assessing their impact on other brain cell types remains challenging due to limitations in current co-culture systems. Here, we developed fully defined brain microtissues, composed of human iPSC-derived neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, co-cultured in 2D or 3D formats. Our microtissues are stable and self-sufficient over time, requiring no exogenous cytokines or growth factors. All three cell types exhibit morphologies characteristic of their in vivo environment and show functional properties. Co-cultured microglia develop more homeostatic phenotypes compared to microglia exposed to exogenous cytokines. Hence, these tri-cultures provide a unique approach to investigate cell-cell interactions between brain cell types. We found that astrocytes and not neurons are sufficient for microglial survival and maturation, and that astrocyte-derived M-CSF is essential for microglial survival. Single-cell and single-nucleus RNA sequencing analyses nominated a network of reciprocal communication between cell types. Brain microtissues faithfully recapitulated pathogenic α-synuclein seeding and aggregation, suggesting their usefulness as human cell models to study not only normal but also pathological cell biological processes.

Markus Wöhr, Wendy M Fong, Justyna A Janas, Moritz Mall, Christian Thome, Madhuri Vangipuram, Lingjun Meng, Thomas C Südhof, Marius Wernig

No abstract

Kelsie Eichel, Takeshi Uenaka, Vivek Belapurkar, Rui Lu, Shouqiang Cheng, Joseph S Pak, Caitlin A Taylor, Thomas C Südhof, Robert Malenka, Marius Wernig, Engin Özkan, David Perrais, Kang Shen

No abstract

Tamara C Chan, Mohit Rastogi, Micah X Williams, Samuel Zhang, Sophia M Shi, Steven R Shuken, Teresa Bartling, Katleen Wild, Micaiah Atkins, Oliver Hahn, Joao A Paulo, Saša Jereb, S Andrew Shuster, Yongjin Yoo, Alan Napole, Victoria G Hernandez, Liqun Luo, Marion S Buckwalter, Beth Stevens, Benjamin E Deverman, Deborah Kronenberg-Versteeg, Steven P Gygi, Tony Wyss-Coray, Marius Wernig

Microglial tiling-the phenomenon of consistent cell-to-cell distances and non-overlapping processes-is regarded as a qualitative indicator of homeostasis, but mechanisms of microglial tiling are unknown. We used cell-surface proximity labeling and mass spectrometry to profile the microglial cell-surface proteome in an in vitro model of homeostatic glial physiology and used single-cell RNA sequencing and public databases to identify candidate cell-surface proteins that might modulate tiling. We designed an image-based functional assay which measures six morphological/spatial readouts to screen these proteins for modulation of tiling. CD72, a coreceptor to the B cell receptor that is expressed by microglia, disrupted tiling; we validated its effects in vitro and in situ in organotypic hippocampal brain slices. Phosphoproteomic studies revealed that CD72 modulates pathways associated with cell adhesion, repulsive receptors, microglial activation, and cytoskeletal organization. These results lay the groundwork for further investigation of the functional roles of tiling in homeostasis and disease.

Microglial tiling-the phenomenon of consistent cell-to-cell distances and non-overlapping processes-is regarded as a qualitative indicator of homeostasis, but mechanisms of microglial tiling are unknown. We used cell-surface proximity labeling and mass spectrometry to profile the microglial cell-surface proteome in an in vitro model of homeostatic glial physiology and used single-cell RNA sequencing and public databases to identify candidate cell-surface proteins that might modulate tiling. We designed an image-based functional assay which measures six morphological/spatial readouts to screen these proteins for modulation of tiling. CD72, a coreceptor to the B cell receptor that is expressed by microglia, disrupted tiling; we validated its effects in vitro and in situ in organotypic hippocampal brain slices. Phosphoproteomic studies revealed that CD72 modulates pathways associated with cell adhesion, repulsive receptors, microglial activation, and cytoskeletal organization. These results lay the groundwork for further investigation of the functional roles of tiling in homeostasis and disease.

Gernot Neumayer, Jessica L Torkelson, Shengdi Li, Kelly McCarthy, Hanson H Zhen, Madhuri Vangipuram, Marius M Mader, Gulilat Gebeyehu, Taysir M Jaouni, Joanna Jacków-Malinowska, Avina Rami, Corey Hansen, Zongyou Guo, Sadhana Gaddam, Keri M Tate, Alberto Pappalardo, Lingjie Li, Grace M Chow, Kevin R Roy, Thuylinh Michelle Nguyen, Koji Tanabe, Patrick S McGrath, Amber Cramer, Anna Bruckner, Ganna Bilousova, Dennis Roop, Jean Y Tang, Angela Christiano, Lars M Steinmetz, Marius Wernig, Anthony E Oro

We present Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Cell Therapy (DEBCT), a scalable platform producing autologous organotypic iPS cell-derived induced skin composite (iSC) grafts for definitive treatment. Clinical-grade manufacturing integrates CRISPR-mediated genetic correction with reprogramming into one step, accelerating derivation of COL7A1-edited iPS cells from patients. Differentiation into epidermal, dermal and melanocyte progenitors is followed by CD49f-enrichment, minimizing maturation heterogeneity. Mouse xenografting of iSCs from four patients with different mutations demonstrates disease modifying activity at 1 month. Next-generation sequencing, biodistribution and tumorigenicity assays establish a favorable safety profile at 1-9 months. Single cell transcriptomics reveals that iSCs are composed of the major skin cell lineages and include prominent holoclone stem cell-like signatures of keratinocytes, and the recently described Gibbin-dependent signature of fibroblasts. The latter correlates with enhanced graftability of iSCs. In conclusion, DEBCT overcomes manufacturing and safety roadblocks and establishes a reproducible, safe, and cGMP-compatible therapeutic approach to heal lesions of DEB patients.

We present Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Cell Therapy (DEBCT), a scalable platform producing autologous organotypic iPS cell-derived induced skin composite (iSC) grafts for definitive treatment. Clinical-grade manufacturing integrates CRISPR-mediated genetic correction with reprogramming into one step, accelerating derivation of COL7A1-edited iPS cells from patients. Differentiation into epidermal, dermal and melanocyte progenitors is followed by CD49f-enrichment, minimizing maturation heterogeneity. Mouse xenografting of iSCs from four patients with different mutations demonstrates disease modifying activity at 1 month. Next-generation sequencing, biodistribution and tumorigenicity assays establish a favorable safety profile at 1-9 months. Single cell transcriptomics reveals that iSCs are composed of the major skin cell lineages and include prominent holoclone stem cell-like signatures of keratinocytes, and the recently described Gibbin-dependent signature of fibroblasts. The latter correlates with enhanced graftability of iSCs. In conclusion, DEBCT overcomes manufacturing and safety roadblocks and establishes a reproducible, safe, and cGMP-compatible therapeutic approach to heal lesions of DEB patients.

Paras S Minhas, Jeffrey R Jones, Amira Latif-Hernandez, Yuki Sugiura, Aarooran S Durairaj, Qian Wang, Siddhita D Mhatre, Takeshi Uenaka, Joshua Crapser, Travis Conley, Hannah Ennerfelt, Yoo Jin Jung, Ling Liu, Praveena Prasad, Brenita C Jenkins, Yeonglong Albert Ay, Matthew Matrongolo, Ryan Goodman, Traci Newmeyer, Kelly Heard, Austin Kang, Edward N Wilson, Tao Yang, Erik M Ullian, Geidy E Serrano, Thomas G Beach, Marius Wernig, Joshua D Rabinowitz, Makoto Suematsu, Frank M Longo, Melanie R McReynolds, Fred H Gage, Katrin I Andreasson

Impaired cerebral glucose metabolism is a pathologic feature of Alzheimer's disease (AD), with recent proteomic studies highlighting disrupted glial metabolism in AD. We report that inhibition of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1), which metabolizes tryptophan to kynurenine (KYN), rescues hippocampal memory function in mouse preclinical models of AD by restoring astrocyte metabolism. Activation of astrocytic IDO1 by amyloid β and tau oligomers increases KYN and suppresses glycolysis in an aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent manner. In amyloid and tau models, IDO1 inhibition improves hippocampal glucose metabolism and rescues hippocampal long-term potentiation in a monocarboxylate transporter-dependent manner. In astrocytic and neuronal cocultures from AD subjects, IDO1 inhibition improved astrocytic production of lactate and uptake by neurons. Thus, IDO1 inhibitors presently developed for cancer might be repurposed for treatment of AD.

Impaired cerebral glucose metabolism is a pathologic feature of Alzheimer's disease (AD), with recent proteomic studies highlighting disrupted glial metabolism in AD. We report that inhibition of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1), which metabolizes tryptophan to kynurenine (KYN), rescues hippocampal memory function in mouse preclinical models of AD by restoring astrocyte metabolism. Activation of astrocytic IDO1 by amyloid β and tau oligomers increases KYN and suppresses glycolysis in an aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent manner. In amyloid and tau models, IDO1 inhibition improves hippocampal glucose metabolism and rescues hippocampal long-term potentiation in a monocarboxylate transporter-dependent manner. In astrocytic and neuronal cocultures from AD subjects, IDO1 inhibition improved astrocytic production of lactate and uptake by neurons. Thus, IDO1 inhibitors presently developed for cancer might be repurposed for treatment of AD.

Teodorus Theo Susanto, Victoria Hung, Andrew G Levine, Yuxiang Chen, Craig H Kerr, Yongjin Yoo, Juan A Oses-Prieto, Lisa Fromm, Zijian Zhang, Travis C Lantz, Kotaro Fujii, Marius Wernig, Alma L Burlingame, Davide Ruggero, Maria Barna

Ribosomes are emerging as direct regulators of gene expression, with ribosome-associated proteins (RAPs) allowing ribosomes to modulate translation. Nevertheless, a lack of technologies to enrich RAPs across sample types has prevented systematic analysis of RAP identities, dynamics, and functions. We have developed a label-free methodology called RAPIDASH to enrich ribosomes and RAPs from any sample. We applied RAPIDASH to mouse embryonic tissues and identified hundreds of potential RAPs, including Dhx30 and Llph, two forebrain RAPs important for neurodevelopment. We identified a critical role of LLPH in neural development linked to the translation of genes with long coding sequences. In addition, we showed that RAPIDASH can identify ribosome changes in cancer cells. Finally, we characterized ribosome composition remodeling during immune cell activation and observed extensive changes post-stimulation. RAPIDASH has therefore enabled the discovery of RAPs in multiple cell types, tissues, and stimuli and is adaptable to characterize ribosome remodeling in several contexts.

Ribosomes are emerging as direct regulators of gene expression, with ribosome-associated proteins (RAPs) allowing ribosomes to modulate translation. Nevertheless, a lack of technologies to enrich RAPs across sample types has prevented systematic analysis of RAP identities, dynamics, and functions. We have developed a label-free methodology called RAPIDASH to enrich ribosomes and RAPs from any sample. We applied RAPIDASH to mouse embryonic tissues and identified hundreds of potential RAPs, including Dhx30 and Llph, two forebrain RAPs important for neurodevelopment. We identified a critical role of LLPH in neural development linked to the translation of genes with long coding sequences. In addition, we showed that RAPIDASH can identify ribosome changes in cancer cells. Finally, we characterized ribosome composition remodeling during immune cell activation and observed extensive changes post-stimulation. RAPIDASH has therefore enabled the discovery of RAPs in multiple cell types, tissues, and stimuli and is adaptable to characterize ribosome remodeling in several contexts.

Ching-Chieh Chou, Ryan Vest, Miguel A Prado, Joshua Wilson-Grady, Joao A Paulo, Yohei Shibuya, Patricia Moran-Losada, Ting-Ting Lee, Jian Luo, Steven P Gygi, Jeffery W Kelly, Daniel Finley, Marius Wernig, Tony Wyss-Coray, Judith Frydman

Aging is a prominent risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (AD), but the cellular mechanisms underlying neuronal phenotypes remain elusive. Both accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain1 and age-linked organelle deficits2-7 are proposed as causes of AD phenotypes but the relationship between these events is unclear. Here, we address this question using a transdifferentiated neuron (tNeuron) model directly from human dermal fibroblasts. Patient-derived tNeurons retain aging hallmarks and exhibit AD-linked deficits. Quantitative tNeuron proteomic analyses identify aging and AD-linked deficits in proteostasis and organelle homeostasis, particularly affecting endosome-lysosomal components. The proteostasis and lysosomal homeostasis deficits in aged tNeurons are exacerbated in sporadic and familial AD tNeurons, promoting constitutive lysosomal damage and defects in ESCRT-mediated repair. We find deficits in neuronal lysosomal homeostasis lead to inflammatory cytokine secretion, cell death and spontaneous development of Aß and phospho-Tau deposits. These proteotoxic inclusions co-localize with lysosomes and damage markers and resemble inclusions in brain tissue from AD patients and APP-transgenic mice. Supporting the centrality of lysosomal deficits driving AD phenotypes, lysosome-function enhancing compounds reduce AD-associated cytokine secretion and Aβ deposits. We conclude that proteostasis and organelle deficits are upstream initiating factors leading to neuronal aging and AD phenotypes.

Aging is a prominent risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (AD), but the cellular mechanisms underlying neuronal phenotypes remain elusive. Both accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain1 and age-linked organelle deficits2-7 are proposed as causes of AD phenotypes but the relationship between these events is unclear. Here, we address this question using a transdifferentiated neuron (tNeuron) model directly from human dermal fibroblasts. Patient-derived tNeurons retain aging hallmarks and exhibit AD-linked deficits. Quantitative tNeuron proteomic analyses identify aging and AD-linked deficits in proteostasis and organelle homeostasis, particularly affecting endosome-lysosomal components. The proteostasis and lysosomal homeostasis deficits in aged tNeurons are exacerbated in sporadic and familial AD tNeurons, promoting constitutive lysosomal damage and defects in ESCRT-mediated repair. We find deficits in neuronal lysosomal homeostasis lead to inflammatory cytokine secretion, cell death and spontaneous development of Aß and phospho-Tau deposits. These proteotoxic inclusions co-localize with lysosomes and damage markers and resemble inclusions in brain tissue from AD patients and APP-transgenic mice. Supporting the centrality of lysosomal deficits driving AD phenotypes, lysosome-function enhancing compounds reduce AD-associated cytokine secretion and Aβ deposits. We conclude that proteostasis and organelle deficits are upstream initiating factors leading to neuronal aging and AD phenotypes.

Yukun A Hao, Sungmoo Lee, Richard H Roth, Silvia Natale, Laura Gomez, Jiannis Taxidis, Philipp S O'Neill, Vincent Villette, Jonathan Bradley, Zeguan Wang, Dongyun Jiang, Guofeng Zhang, Mengjun Sheng, Di Lu, Edward Boyden, Igor Delvendahl, Peyman Golshani, Marius Wernig, Daniel E Feldman, Na Ji, Jun Ding, Thomas C Südhof, Thomas R Clandinin, Michael Z Lin

A remaining challenge for genetically encoded voltage indicators (GEVIs) is the reliable detection of excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs). Here, we developed ASAP5 as a GEVI with enhanced activation kinetics and responsivity near resting membrane potentials for improved detection of both spiking and subthreshold activity. ASAP5 reported action potentials (APs) in vivo with higher signal-to-noise ratios than previous GEVIs and successfully detected graded and subthreshold responses to sensory stimuli in single two-photon trials. In cultured rat or human neurons, somatic ASAP5 reported synaptic events propagating centripetally and could detect ∼1-mV EPSPs. By imaging spontaneous EPSPs throughout dendrites, we found that EPSP amplitudes decay exponentially during propagation and that amplitude at the initiation site generally increases with distance from the soma. These results extend the applications of voltage imaging to the quantal response domain, including in human neurons, opening up the possibility of high-throughput, high-content characterization of neuronal dysfunction in disease.

A remaining challenge for genetically encoded voltage indicators (GEVIs) is the reliable detection of excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs). Here, we developed ASAP5 as a GEVI with enhanced activation kinetics and responsivity near resting membrane potentials for improved detection of both spiking and subthreshold activity. ASAP5 reported action potentials (APs) in vivo with higher signal-to-noise ratios than previous GEVIs and successfully detected graded and subthreshold responses to sensory stimuli in single two-photon trials. In cultured rat or human neurons, somatic ASAP5 reported synaptic events propagating centripetally and could detect ∼1-mV EPSPs. By imaging spontaneous EPSPs throughout dendrites, we found that EPSP amplitudes decay exponentially during propagation and that amplitude at the initiation site generally increases with distance from the soma. These results extend the applications of voltage imaging to the quantal response domain, including in human neurons, opening up the possibility of high-throughput, high-content characterization of neuronal dysfunction in disease.

Marius Marc-Daniel Mader, Alan Napole, Danwei Wu, Micaiah Atkins, Alexa Scavetti, Yohei Shibuya, Aulden Foltz, Oliver Hahn, Yongjin Yoo, Ron Danziger, Christina Tan, Tony Wyss-Coray, Lawrence Steinman, Marius Wernig

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease characterized by demyelination of the central nervous system (CNS). Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) shows promising benefits for relapsing-remitting MS in open-label clinical studies, but the cellular mechanisms underlying its therapeutic effects remain unclear. Using single-nucleus RNA sequencing, we identify a reactive myeloid cell state in chronic experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) associated with neuroprotection and immune suppression. HCT in EAE mice results in an increase of the neuroprotective myeloid state, improvement of neurological deficits, reduced number of demyelinated lesions, decreased number of effector T cells and amelioration of reactive astrogliosis. Enhancing myeloid cell incorporation after a modified HCT further improved these neuroprotective effects. These data suggest that myeloid cell manipulation or replacement may be an effective therapeutic strategy for chronic inflammatory conditions of the CNS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease characterized by demyelination of the central nervous system (CNS). Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) shows promising benefits for relapsing-remitting MS in open-label clinical studies, but the cellular mechanisms underlying its therapeutic effects remain unclear. Using single-nucleus RNA sequencing, we identify a reactive myeloid cell state in chronic experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) associated with neuroprotection and immune suppression. HCT in EAE mice results in an increase of the neuroprotective myeloid state, improvement of neurological deficits, reduced number of demyelinated lesions, decreased number of effector T cells and amelioration of reactive astrogliosis. Enhancing myeloid cell incorporation after a modified HCT further improved these neuroprotective effects. These data suggest that myeloid cell manipulation or replacement may be an effective therapeutic strategy for chronic inflammatory conditions of the CNS.

Cheen Euong Ang, Victor Hipolito Olmos, Kayla Vodehnal, Bo Zhou, Qian Yi Lee, Rahul Sinha, Aadit Narayanaswamy, Moritz Mall, Kirill Chesnov, Caia S Dominicus, Thomas Südhof, Marius Wernig

Generation of defined neuronal subtypes from human pluripotent stem cells remains a challenge. The proneural factor NGN2 has been shown to overcome experimental variability observed by morphogen-guided differentiation and directly converts pluripotent stem cells into neurons, but their cellular heterogeneity has not been investigated yet. Here, we found that NGN2 reproducibly produces three different kinds of excitatory neurons characterized by partial coactivation of other neurotransmitter programs. We explored two principle approaches to achieve more precise specification: prepatterning the chromatin landscape that NGN2 is exposed to and combining NGN2 with region-specific transcription factors. Unexpectedly, the chromatin context of regionalized neural progenitors only mildly altered genomic NGN2 binding and its transcriptional response and did not affect neurotransmitter specification. In contrast, coexpression of region-specific homeobox factors such as EMX1 resulted in drastic redistribution of NGN2 including recruitment to homeobox targets and resulted in glutamatergic neurons with silenced nonglutamatergic programs. These results provide the molecular basis for a blueprint for improved strategies for generating a plethora of defined neuronal subpopulations from pluripotent stem cells for therapeutic or disease-modeling purposes.

Generation of defined neuronal subtypes from human pluripotent stem cells remains a challenge. The proneural factor NGN2 has been shown to overcome experimental variability observed by morphogen-guided differentiation and directly converts pluripotent stem cells into neurons, but their cellular heterogeneity has not been investigated yet. Here, we found that NGN2 reproducibly produces three different kinds of excitatory neurons characterized by partial coactivation of other neurotransmitter programs. We explored two principle approaches to achieve more precise specification: prepatterning the chromatin landscape that NGN2 is exposed to and combining NGN2 with region-specific transcription factors. Unexpectedly, the chromatin context of regionalized neural progenitors only mildly altered genomic NGN2 binding and its transcriptional response and did not affect neurotransmitter specification. In contrast, coexpression of region-specific homeobox factors such as EMX1 resulted in drastic redistribution of NGN2 including recruitment to homeobox targets and resulted in glutamatergic neurons with silenced nonglutamatergic programs. These results provide the molecular basis for a blueprint for improved strategies for generating a plethora of defined neuronal subpopulations from pluripotent stem cells for therapeutic or disease-modeling purposes.

Yang Song, Jennifer Soto, Sze Yue Wong, Yifan Wu, Tyler Hoffman, Navied Akhtar, Sam Norris, Julia Chu, Hyungju Park, Douglas O Kelkhoff, Cheen Euong Ang, Marius Wernig, Andrea Kasko, Timothy L Downing, Mu-Ming Poo, Song Li

We investigate how matrix stiffness regulates chromatin reorganization and cell reprogramming and find that matrix stiffness acts as a biphasic regulator of epigenetic state and fibroblast-to-neuron conversion efficiency, maximized at an intermediate stiffness of 20 kPa. ATAC sequencing analysis shows the same trend of chromatin accessibility to neuronal genes at these stiffness levels. Concurrently, we observe peak levels of histone acetylation and histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity in the nucleus on 20 kPa matrices, and inhibiting HAT activity abolishes matrix stiffness effects. G-actin and cofilin, the cotransporters shuttling HAT into the nucleus, rises with decreasing matrix stiffness; however, reduced importin-9 on soft matrices limits nuclear transport. These two factors result in a biphasic regulation of HAT transport into nucleus, which is directly demonstrated on matrices with dynamically tunable stiffness. Our findings unravel a mechanism of the mechano-epigenetic regulation that is valuable for cell engineering in disease modeling and regenerative medicine applications.

We investigate how matrix stiffness regulates chromatin reorganization and cell reprogramming and find that matrix stiffness acts as a biphasic regulator of epigenetic state and fibroblast-to-neuron conversion efficiency, maximized at an intermediate stiffness of 20 kPa. ATAC sequencing analysis shows the same trend of chromatin accessibility to neuronal genes at these stiffness levels. Concurrently, we observe peak levels of histone acetylation and histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity in the nucleus on 20 kPa matrices, and inhibiting HAT activity abolishes matrix stiffness effects. G-actin and cofilin, the cotransporters shuttling HAT into the nucleus, rises with decreasing matrix stiffness; however, reduced importin-9 on soft matrices limits nuclear transport. These two factors result in a biphasic regulation of HAT transport into nucleus, which is directly demonstrated on matrices with dynamically tunable stiffness. Our findings unravel a mechanism of the mechano-epigenetic regulation that is valuable for cell engineering in disease modeling and regenerative medicine applications.

Diane L Haakonsen, Michael Heider, Andrew J Ingersoll, Kayla Vodehnal, Samuel R Witus, Takeshi Uenaka, Marius Wernig, Michael Rapé

Stress response pathways detect and alleviate adverse conditions to safeguard cell and tissue homeostasis, yet their prolonged activation induces apoptosis and disrupts organismal health1-3 . How stress responses are turned off at the right time and place remains poorly understood. Here we report a ubiquitin-dependent mechanism that silences the cellular response to mitochondrial protein import stress. Crucial to this process is the silencing factor of the integrated stress response (SIFI), a large E3 ligase complex mutated in ataxia and in early-onset dementia that degrades both unimported mitochondrial precursors and stress response components. By recognizing bifunctional substrate motifs that equally encode protein localization and stability, the SIFI complex turns off a general stress response after a specific stress event has been resolved. Pharmacological stress response silencing sustains cell survival even if stress resolution failed, which underscores the importance of signal termination and provides a roadmap for treating neurodegenerative diseases caused by mitochondrial import defects.

Stress response pathways detect and alleviate adverse conditions to safeguard cell and tissue homeostasis, yet their prolonged activation induces apoptosis and disrupts organismal health1-3 . How stress responses are turned off at the right time and place remains poorly understood. Here we report a ubiquitin-dependent mechanism that silences the cellular response to mitochondrial protein import stress. Crucial to this process is the silencing factor of the integrated stress response (SIFI), a large E3 ligase complex mutated in ataxia and in early-onset dementia that degrades both unimported mitochondrial precursors and stress response components. By recognizing bifunctional substrate motifs that equally encode protein localization and stability, the SIFI complex turns off a general stress response after a specific stress event has been resolved. Pharmacological stress response silencing sustains cell survival even if stress resolution failed, which underscores the importance of signal termination and provides a roadmap for treating neurodegenerative diseases caused by mitochondrial import defects.

Teodorus Theo Susanto, Victoria Hung, Andrew G Levine, Craig H Kerr, Yongjin Yoo, Yuxiang Chen, Juan A Oses-Prieto, Lisa Fromm, Kotaro Fujii, Marius Wernig, Alma Burlingame, Davide Ruggero, Maria Barna

Ribosomes are emerging as direct regulators of gene expression, with ribosome-associated proteins (RAPs) allowing ribosomes to modulate translational control. However, a lack of technologies to enrich RAPs across many sample types has prevented systematic analysis of RAP number, dynamics, and functions. Here, we have developed a label-free methodology called RAPIDASH to enrich ribosomes and RAPs from any sample. We applied RAPIDASH to mouse embryonic tissues and identified hundreds of potential RAPs, including DHX30 and LLPH, two forebrain RAPs important for neurodevelopment. We identified a critical role of LLPH in neural development that is linked to the translation of genes with long coding sequences. Finally, we characterized ribosome composition remodeling during immune activation and observed extensive changes post-stimulation. RAPIDASH has therefore enabled the discovery of RAPs ranging from those with neuroregulatory functions to those activated by immune stimuli, thereby providing critical insights into how ribosomes are remodeled.

Ribosomes are emerging as direct regulators of gene expression, with ribosome-associated proteins (RAPs) allowing ribosomes to modulate translational control. However, a lack of technologies to enrich RAPs across many sample types has prevented systematic analysis of RAP number, dynamics, and functions. Here, we have developed a label-free methodology called RAPIDASH to enrich ribosomes and RAPs from any sample. We applied RAPIDASH to mouse embryonic tissues and identified hundreds of potential RAPs, including DHX30 and LLPH, two forebrain RAPs important for neurodevelopment. We identified a critical role of LLPH in neural development that is linked to the translation of genes with long coding sequences. Finally, we characterized ribosome composition remodeling during immune activation and observed extensive changes post-stimulation. RAPIDASH has therefore enabled the discovery of RAPs ranging from those with neuroregulatory functions to those activated by immune stimuli, thereby providing critical insights into how ribosomes are remodeled.

Katie Schaukowitch, Justyna A Janas, Marius Wernig

Direct neuronal reprogramming converts somatic cells of a defined lineage into induced neuronal cells without going through a pluripotent intermediate. This approach not only provides access to the otherwise largely inaccessible cells of the brain for neuronal disease modeling, but also holds great promise for ultimately enabling neuronal cell replacement without the use of transplantation. To improve efficiency and specificity of direct neuronal reprogramming, much of the current efforts aim to understand the mechanisms that safeguard cell identities and how the reprogramming cells overcome the barriers resisting fate changes. Here, we review recent discoveries into the mechanisms by which the donor cell program is silenced, and new cell identities are established. We also discuss advancements that have been made toward fine-tuning the output of these reprogramming systems to generate specific types of neuronal cells. Finally, we highlight the benefit of using direct neuronal reprogramming to study age-related disorders and the potential of in vivo direct reprogramming in regenerative medicine.

Direct neuronal reprogramming converts somatic cells of a defined lineage into induced neuronal cells without going through a pluripotent intermediate. This approach not only provides access to the otherwise largely inaccessible cells of the brain for neuronal disease modeling, but also holds great promise for ultimately enabling neuronal cell replacement without the use of transplantation. To improve efficiency and specificity of direct neuronal reprogramming, much of the current efforts aim to understand the mechanisms that safeguard cell identities and how the reprogramming cells overcome the barriers resisting fate changes. Here, we review recent discoveries into the mechanisms by which the donor cell program is silenced, and new cell identities are established. We also discuss advancements that have been made toward fine-tuning the output of these reprogramming systems to generate specific types of neuronal cells. Finally, we highlight the benefit of using direct neuronal reprogramming to study age-related disorders and the potential of in vivo direct reprogramming in regenerative medicine.

Margaret G Guo, David L Reynolds, Cheen E Ang, Yingfei Liu, Yang Zhao, Laura K H Donohue, Zurab Siprashvili, Xue Yang, Yongjin Yoo, Smarajit Mondal, Audrey Hong, Jessica Kain, Lindsey Meservey, Tania Fabo, Ibtihal Elfaki, Laura N Kellman, Nathan S Abell, Yash Pershad, Vafa Bayat, Payam Etminani, Mark Holodniy, Daniel H Geschwind, Stephen B Montgomery, Laramie E Duncan, Alexander E Urban, Russ B Altman, Marius Wernig, Paul A Khavari

Noncoding variants of presumed regulatory function contribute to the heritability of neuropsychiatric disease. A total of 2,221 noncoding variants connected to risk for ten neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia, were studied in developing human neural cells. Integrating epigenomic and transcriptomic data with massively parallel reporter assays identified differentially-active single-nucleotide variants (daSNVs) in specific neural cell types. Expression-gene mapping, network analyses and chromatin looping nominated candidate disease-relevant target genes modulated by these daSNVs. Follow-up integration of daSNV gene editing with clinical cohort analyses suggested that magnesium transport dysfunction may increase neuropsychiatric disease risk and indicated that common genetic pathomechanisms may mediate specific symptoms that are shared across multiple neuropsychiatric diseases.

Noncoding variants of presumed regulatory function contribute to the heritability of neuropsychiatric disease. A total of 2,221 noncoding variants connected to risk for ten neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia, were studied in developing human neural cells. Integrating epigenomic and transcriptomic data with massively parallel reporter assays identified differentially-active single-nucleotide variants (daSNVs) in specific neural cell types. Expression-gene mapping, network analyses and chromatin looping nominated candidate disease-relevant target genes modulated by these daSNVs. Follow-up integration of daSNV gene editing with clinical cohort analyses suggested that magnesium transport dysfunction may increase neuropsychiatric disease risk and indicated that common genetic pathomechanisms may mediate specific symptoms that are shared across multiple neuropsychiatric diseases.

Yongjin Yoo, Gernot Neumayer, Yohei Shibuya, Marius Marc-Daniel Mader, Marius Wernig

Marius Wernig

wernig@stanford.edu

Dr. Marius Wernig is a Professor of Pathology and a Co-Director of the Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine at Stanford University. He graduated with an M.D. Ph.D. from the Technical University of Munich where he trained in developmental genetics in the lab of Rudi Balling. After completing his residency in Neuropathology and General Pathology at the University of Bonn, he then became a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Dr. Rudolf Jaenisch at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research/ MIT in Cambridge, MA. In 2008, Dr. Wernig joined the faculty of the Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine at Stanford University where he has been ever since.

He received an NIH Pathway to Independence Award, the Cozzarelli Prize for Outstanding Scientific Excellence from the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A., the Outstanding Investigator Award from the International Society for Stem Cell Research, the New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Stem Cell Prize, the Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize delivered by the Gladstone Institute and more recently has been named a Faculty Scholar by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Dr. Wernig’s lab is interested in pluripotent stem cell biology and the molecular determinants of neural cell fate decisions. His laboratory was the first to generate functional neuronal cells reprogrammed directly from skin fibroblasts, which he termed induced neuronal (iN) cells. The lab is now working on identifying the molecular mechanisms underlying induced lineage fate changes, the phenotypic consequences of disease-causing mutations in human neurons and other neural lineages as well as the development of novel therapeutic gene targeting and cell transplantation-based strategies for a variety of monogenetic diseases.

Academic appointments

Associate Professor Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine

Member:

Bio-X

Cardiovascular Institute

Child Health Research Institute

Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine

Stanford Cancer Institute

Stanford Neurosciences Institute

Administrative appointments

Faculty Senate, Department of Pathology (2017 - Present)

Assistant Professor, Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine (2008 - 2014)

Honors & Awards

HHMI Faculty Scholar Award, Howard Hughes Medical Institute (2016)

New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Stem Cell Prize, New York Stem Cell Foundation (2014)

The Outstanding Young Investigator Award, International Society for Stem Cell Research (2013)

Ascina Award, Republic of Austria (2010)

Cozzarelli Prize for Outstanding Scientific Excellence, National Academy of Sciences USA (2009)

New Scholar in Aging, Ellison Medical Foundation (2010)

Robertson Investigator Award, New York Stem Cell Foundation (2010)

Donald E. and Delia B. Baxter Faculty Scholarship, Stanford University (2009)

Margaret and Herman Sokol Award, Biomedical Research (2007)

Longterm fellowship Human Frontiers Science Program Organisation, HFSP (2004-2006)

Boards, Advisory Committees

Professional Organizations Member, Society for Neuroscience (2003 - Present)

Member, International Society for Stem Cell Research (2004 - Present)

Editorial Board Member, Cell Stem Cell (2012 - Present)

Editorial Board Member, Stem Cell Reports (2013 - Present)

Member, Program Committee, Society for Neuroscience (2016 - Present)

Chair, Program Committee, International Society for Stem Cell Research (2017 - Present)

Professional Education

M.D., Technical University of Munich, Medicine (2000)

Team

I joined the Wernig lab as an LSRP in the summer of 2022 after graduating from UCLA. I’m interested in the regenerative capabilities of the human body and the molecular mechanisms underlying these regenerative systems, as well as the ways in which we can utilize these mechanisms to treat disease via tools such as cell and gene therapy. My research interests further include immunological topics such as cancer biology and the coevolution of pathogenic species and the immune response. In the Wernig lab, I am investigating methods of replacing dysfunctional microglia in the CNS in the context of neurodegenerative diseases, as well as the translational potential of gene editing and the role that genetically manipulated cells can play in treating such diseases. Outside the lab, I enjoy spending time at the beach, watching sports, and going on road trips with my friends.

Danwei Wu is a Stanford neurology resident in the Neuroscience Scholar Track and aspiring neuroimmunologist. Prior to starting residency, she completed an HHMI Medical Research Fellowship with Dr. Vann Bennett at Duke University studying neuron-specific membrane domains and their interaction with cytoskeletal structures. Her current research interest includes cell-based therapies for multiple sclerosis, molecular pathways of neuro-repair, and pathogenesis of autoimmunity. She is interested in developing new therapies for neurologic diseases. Outside of the lab, she enjoys hiking and reading science fiction.

I am a PhD student in the Neurosciences Interdepartmental Program and joined the lab in summer 2022. I am interested in developing methods to reprogram stem cells directly into oligodendrocytes. I then hope to use these cells to study the role of oligodendrocytes in aging and neurodegeneration. In my free time I like to read, ski, and play tennis.

I am a passionate cellular and molecular biologistwith expertise in research related to cancer, genomic/chromosomal instability, DNA damage response, epigenetics, proteomics and cellular identity. The latter topic attracted me to the Wernig lab where I aim to decipher the mechanisms that allow us to specifically switch the identity of a cell, converting differentiated somatic cells into induced neurons. I also work on a project that aims to integrate CRISPR/CAS9-mediated gene correction with iPS cell generation in order to establish a therapy for the devastating skin disease epidermolysis bullosa. In my free time I play underwater rugby, surf, spearfish and ski!

I am an undergraduate studying neurobiology and computer science. In the Wernig Lab, I am studying how the interactions between reprogramming factors and chromatin modifiers allow for fully developed fibrojacklynl@stanford.edublasts to reprogram into induced neuronal cells (iN).

I studied small GTPase signaling and how its perturbation can contribute to cancer and neurological disorders during my PhD training at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Since then, I have become increasingly fascinated by the epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation, and how changes in epigenome influence cell function and fate decisions. In the Wernig lab, I am currently investigating the interactions between the reprogramming factors and chromatin modifiers. More specifically, I am interested in finding out how such interactions enable a terminally differentiated cell—for example, a fibroblast—to acquire new transcriptional program that allows its reprogramming into induced neuron (iN).

I am a Bachelor of Science candidate in Bioengineering at Stanford University. My research in the Wernig Lag involves investigating the relationship between microglia and the IKBKAP gene, specifically its role in mechanisms such as microglia regeneration and the transdifferentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells into microglia-like cells.

Kayla is a PhD student in the Neurosciences Interdepartmental Program and joined the lab in summer 2022. She is interested in leveraging the lab's cell reprogramming techniques to study the roles of individual cell types in proteinopathies. She aims to faithfully recapitulate disease states and uncover the underlying molecular mechanisms that lead to neurodegeneration. In her free time, Kayla can be found birding, hiking, or performing with the Stanford Symphony Orchestra.

I received my BA in molecular and cell biology (Neurobiology focus) and computer science from UC Berkeley. I went on to do my PhD at Duke University, where I worked on engineering electrical synapses for precise neuromodulation in Kafui Dzirasa’s lab. Now, as a postdoc in Marius Wernig lab, I am interested in delving deeper into cellular engineering to better understand neuronal induction, synapse formation, and deliver treatment across the blood brain barrier using engineered microglia. In my free time, I enjoy cooking and coding/electrical engineering projects.

As a neurosurgical resident, my research interests include translational topics such as cell therapy and neuroregenerative mechanisms. In the Wernig lab, I study the cellular reprogramming potential of microglia. Moreover, I’m interested in the functional integration of induced neurons into neural systems.

I am an undergraduate student studying Human Biology. At Wernig Lab, I am helping to research how microglial cells organize and communicate with each other. I am interested in understanding the relationship between changes in the organization of microglia and other neural cells and the progression of neuronal diseases.

I received my Ph.D. in Neuroscience and Brain Technologies in 2021 from the University of Genoa and the Italian Institute of Technology, Italy. I joined the Wernig lab in December 2022. Here, I am interested in understanding how the microglia-derived factors end up in the neuronal lysosomes. Furthermore, I am interested in understanding how the accumulation and breakdown of these factors lead to neurodegenerative disorders using human induced pluripotent stem cell culture. I read non-fiction novels, sketch, and go for hikes in my free time.

Rida Rehman received her doctorate in Natural Sciences (Dr. Rer. Nat.), specializing in brain trauma and rehabilitation at Universtät Ulm, Germany in 2023. She also holds an M.S. in Biomedical Sciences and a B.S. in Applied Biosciences from NUST, Pakistan. Rida’s research has primarily focused on understanding the critical role of microglia in neurotrauma, degeneration, reprogramming and repair. Rida joined Wernig lab in 2023 and is primarily working on microglia to neuron reprogramming.

I worked as a neurologist for 10 years in Japan. During clinical practice, I saw a lot of patients who could not be treated by the current medicine. As a result, I became strongly attracted to basic research of neuroscience. I received my PhD in Dr. Tatsushi Toda’s lab at Kobe University, where I studied disease-modifying drug for Parkinson’s disease. As a post doc fellow in the Wernig lab, I’m interested in investigating the ubiquitylation enzymes that are associated with the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease in order to cure patients with neurodegenerative diseases in the future. In my free time, I play with my children, go cycling, and read comics.

I am a PhD student in the Department of Neurosciences and I joined the Wernig lab in the summer of 2020. I hope to study the fundamental cell biology of microglia giving rise to stable tiling in the brain. Furthermore, I am interested in how these mechanisms contribute to brain homeostasis and change with neuronal disease.

During my PhD in Yongjuan Zhao and Honcheung Lee’s lab, I focused on studying the enzymatic activity and function of ADP-ribosyl cyclase, particularly the activity of SARM1 and its role in axon degeneration. This work sparked my interest in neuroscience and neuropathology. Microglia, the resident immune cells in the brain, play critical roles in neuronal function and can be either beneficial or detrimental in the context of neurodegenerative diseases.In Wernig’s lab, I am interested in investigating the function of microglia in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. My current research focuses on understanding the effects of clonal hematopoietic mutations on microglia and their role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

I'm excited about diving into the mysteries of cell fate changes at both the cellular and molecular biology levels, using both experimental and computational tools. In the Wernig lab, I'm on a fascinating journey exploring methods to reprogramm cells into specific neuronal fates. Plus, I'm eager to unravel the basic transcriptional regulation codes in these processes.

Alumni

.gif)

Alan Napole was an LSRP working on elucidating the mechanisms of transgene silencing following iN differentiation from pluripotent stem cells. Concurrently, Alan is also working on understanding the role of microglia in multiple sclerosis via EAE mice models. Previously, he was a CIRM scholar working closely with microglia replacement strategies to develop a human mouse microglia chimera for investigation of neuroimmunological diseases. Alan is currently applying to medical school with interests in neuroscience and surgery. Outside of the lab, he enjoys attending music festivals, playing soccer, and cooking. He moved on to grad school in his home town LA. We wish him all the best for his future endeavors!

Angel earned his B.S. in Biology at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. As an undergraduate he studied the effects of nicotine on diabetic individuals. As a CIRM fellow at Stanford University, he is interested in using microglia cell replacement and stem cell technology as a potential therapeutic for neurological disorders. Unfortunately, COVID19 cut some of the last of his time he was planning to stay with us. We are proud of Angel that he got into the PhD program at UC Irvine where he moved during these challenging times of natural disasters of the year 2020. Good luck Angel!

Bahareh's research interests were focused on epigenetic regulation of cognition at the level of synapses, using iN system. In my free time she likes to do sports and outdoor activities, cook healthy food, make mixed drinks, play music, and collect vinyl records. After graduating from our Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine PhD program she moved on as postdoctoral fellow to Boston.

Cheen Euong Ang was a bioengineering PhD student in the Wernig lab. He spent his undergraduate career at McGill University, graduating with a B.Sc. in Chemistry with a focus in biological chemistry. Since coming to Stanford, Cheen Euong has been working on investigating the mechanisms of iN reprogramming and applying the iN platform in disease modeling and aging. Other than doing research in the lab, Cheen Euong has participated several scientific outreach programs such as the Stanford Biomedical Engineering Society undergraduate academic mentoring program and Stanford Institute of Medical Summer High School Student Research Program. Cheen moved on to do his postdoc in Xiaowei Zhuang at Harvard University in Cambridge, MA.

Christian's project focused on the function of synaptic proteins in the context of human neurons. Brain research has made tremendous advances in the last decades using animal models. However, most neuropathological conditions, such as autism or schizophrenia, are unique to human physiology. Thus, I study the effect of genetic alterations of synaptic proteins in induced human neurons using immunohistochemistry, analysis of gene and protein expression, as well as electrophysiology. Christian moved on to a senior lecturer position at the newly formed university of Linz, Austria. Good luck there!

Graduating from UC Berkeley majoring in Biology with an honors in Neuroscience, and having worked as an MD at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, I have developed a particular interest in translational neuroscience. In the lab, I am investigating the efficacy of cell therapies for neurological disorders. I am currently working on microglia based therapies for major neurological diseases, including multiple sclerosis.

I am a molecular biologist with a focus on neuro- and cancer biology. I am interested in using human iPSCs to develop new in vitro disease models, particularly for neuropsychiatric disorders and neurooncology. This led me to the Wernig lab where I started my postdoc to explore the advantages of direct neuronal reprogramming and the intricacies of step-wise differentiation of neural cell types. I am genetically engineering iPSC lines to generate complex genomic alterations and inducible mutations. Following differentiation into the corresponding disease-relevant tissue, I am puzzling together cellular phenotypes, transcriptional regulation, protein interactions, and epigenetic changes for a better understanding of the disease biology. In my spare time, I enjoy a new definition of chaos by my 2-year-old daughter.

Hiroko received Ph.D. from UCLA Neuroscience program in Jim Waschek's lab. She's currently a postdoc studying the disease mechanism of pediatric brain disorder Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disorder, affecting oligodendrocyte development and myelination. She uses patient-derived iPS cells, gene targeting in iPS cells, and animal models.

I was an administrative associate for the Wernig Lab for a brief period in 2019. I am a native San Franciscan and I love the bay area. I received my undergrad from San Francisco State. I am fluent inSpanish so if you ever need a Spanish lesson come by desk. My husband and I have three beautiful childrenand during my time off I really enjoying spending time with my family.

I grew up in Long Island, NY. I attended college at Cornell University majoring in Biological Sciences with a concentration in Neurobiology and Behavior. After graduation in 2009, I moved to Nashville, TN to join the Medical Scientist Training Program at Vanderbilt University where I earned a combined MD/PhD. In 2016, I started my residency in Neurosurgery at Stanford. In the Wernig lab, I am interested in developing microglia-based regenerative therapies for neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders.