Wernig Laboratory

October 9, 2024: Welcome new postdoc Kirill to the lab!

Sep 17, 2024: Jinzhao's paper accepted in principle!

Jul 11, 2024: Gernot's paper published in Nature Communications!

March 21, 2024: Marius Mader's paper comes out in Nature Neuroscience!

Oct 10, 2023: Yongjin receives the Sammy Kuo Award from the Neuroscience Institute - CONGRATULATIONS!

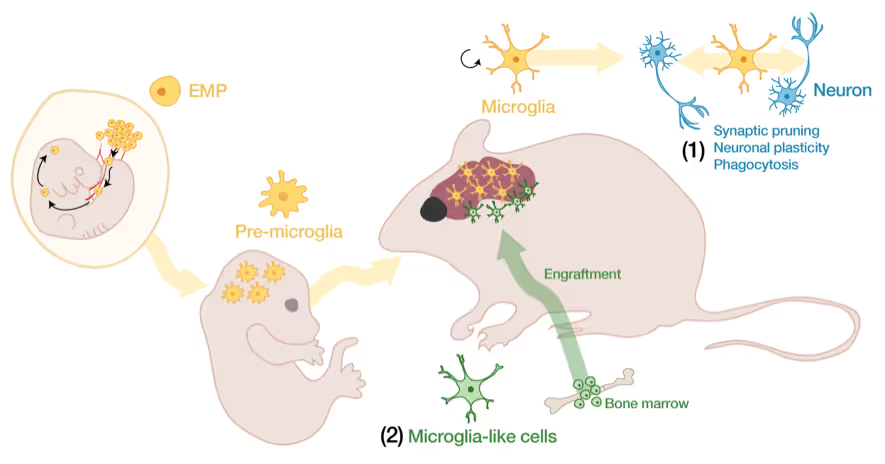

Yongjin's paper on cell therapy in a mouse AD model is published in Cell Stem Cells

Our lab is generally interested in the molecular mechanisms that determine cell fates

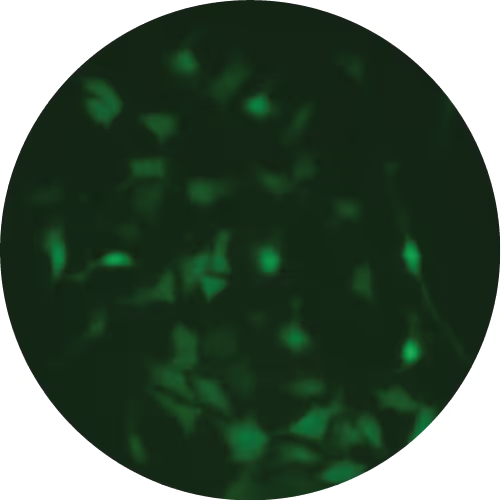

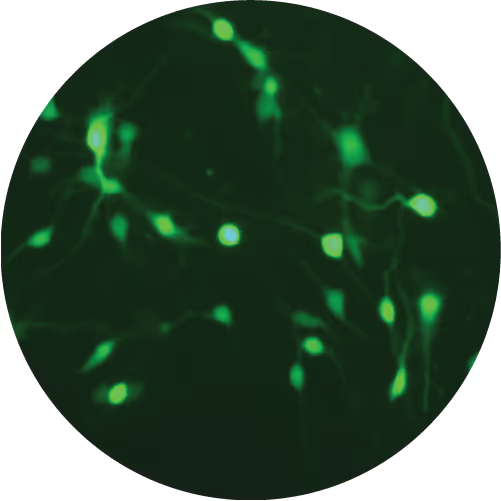

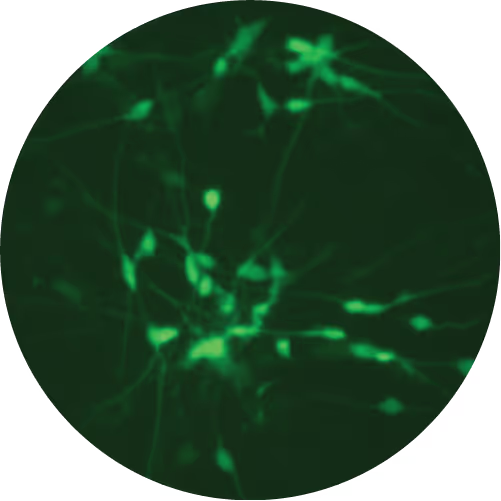

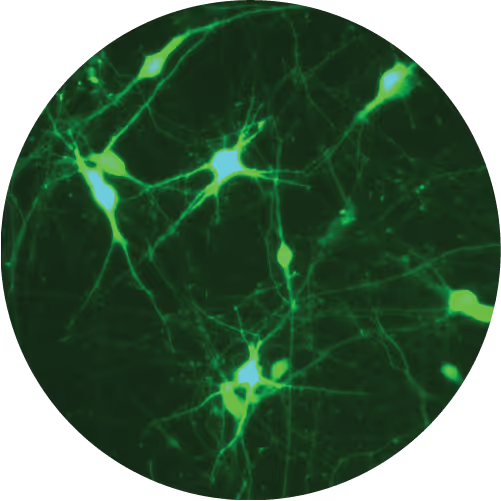

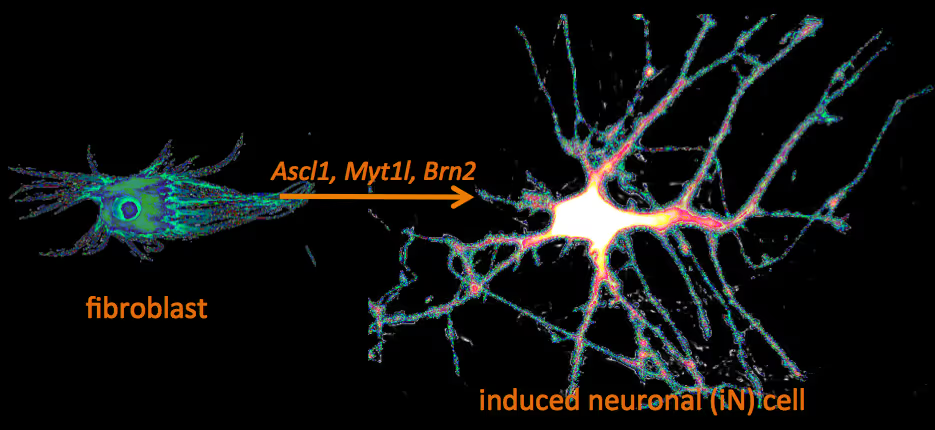

Recently, we have identified a pool of transcription factors that are sufficient to convert skin fibroblasts directly into functional neuronal cells that we termed induced neuronal (iN) cells. This was a surprising finding and indicated that direct lineage reprogramming may be applicable to many somatic cell types and many different directions. Indeed, following our work others have identified transcription factors that could induce cardiomyocytes, blood progenitors, and hepatocytes from fibroblasts.

We are now focussing on two major aspects of iN and iPS cell reprogramming:

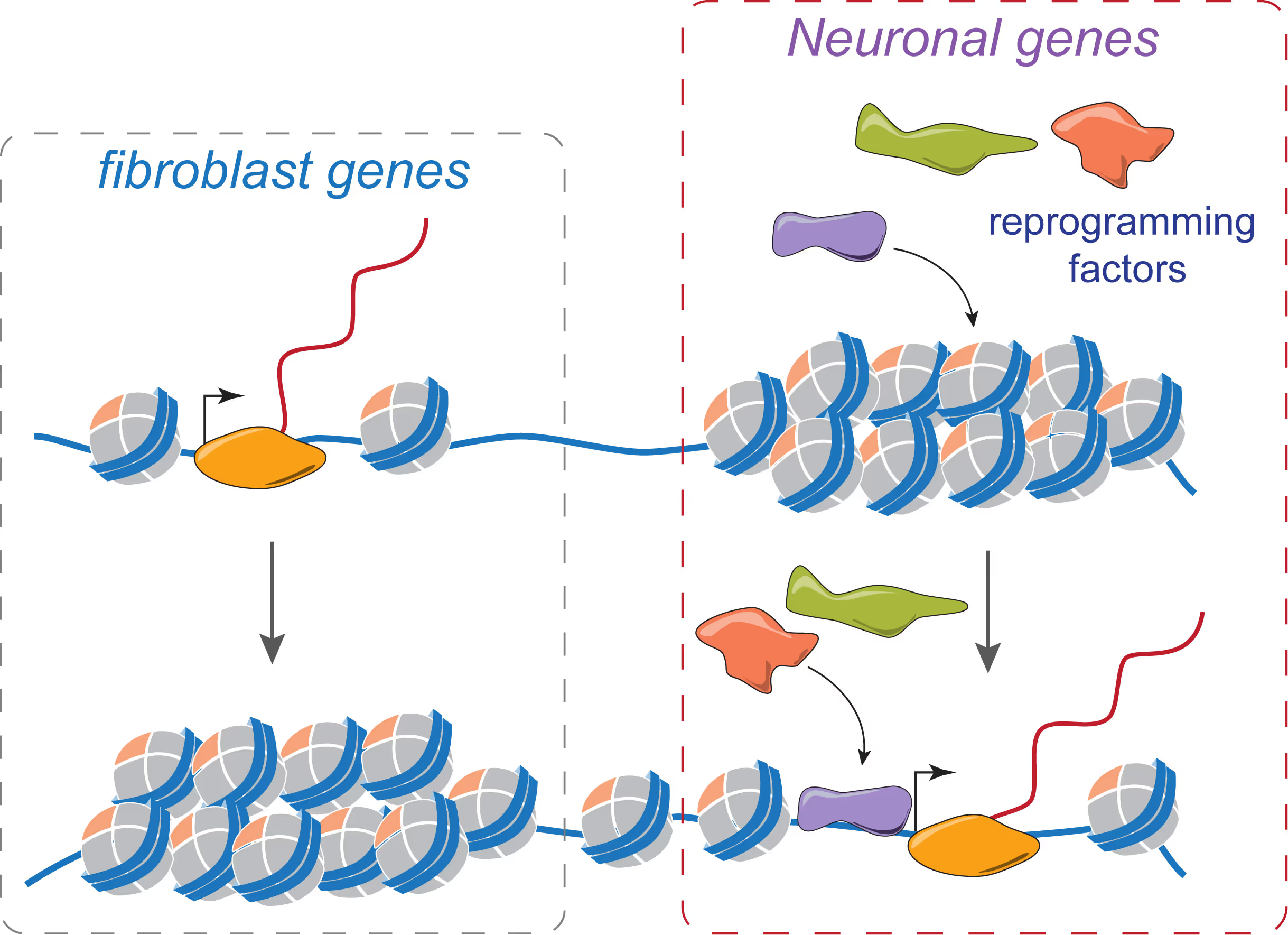

(i) we are fascinated by the puzzle how a hand full of transcription factors can so efficiently reprogram the entire epigenome of a cell so that it changes identity. To that end we are applying genome-wide expression analysis, chromatin immunoprecipitation, protein biochemistry, proteomics and functional screens.

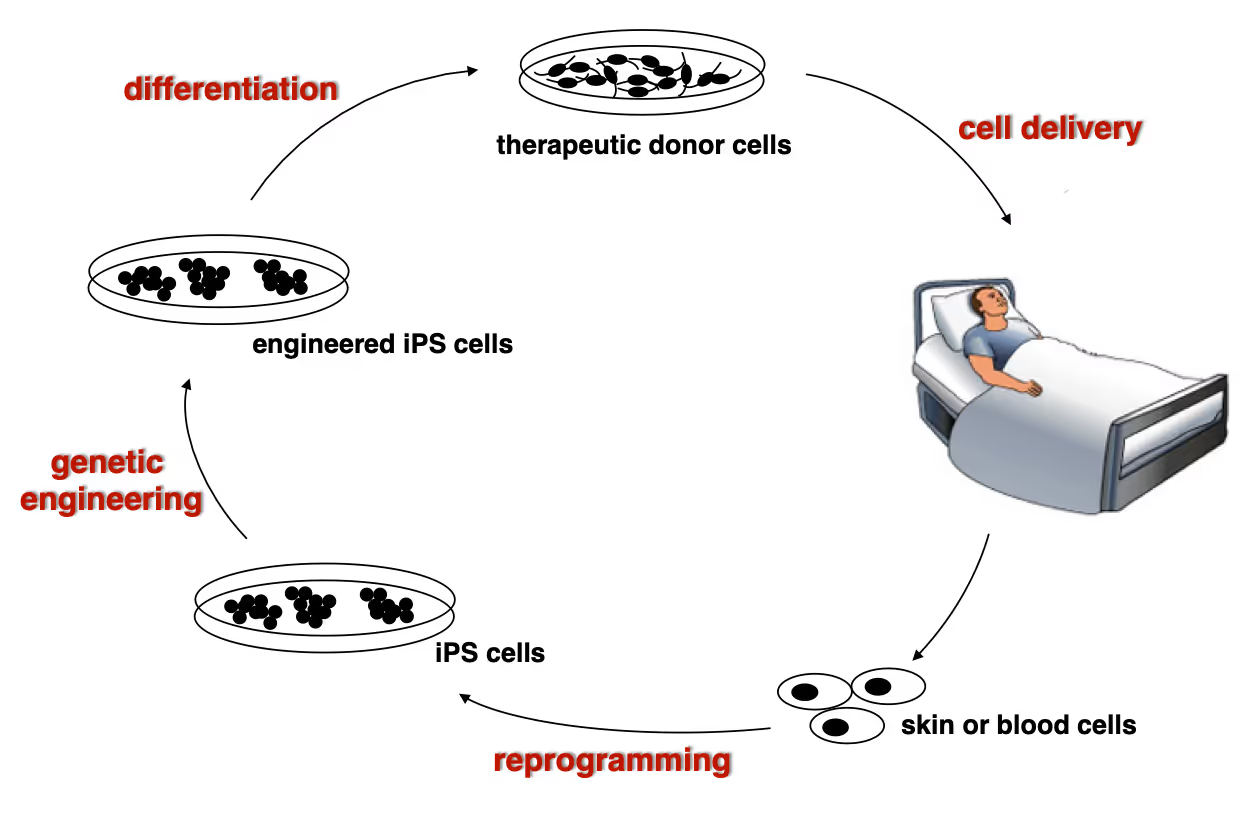

(ii) it is equally exciting to now use reprogramming methods as tools to study or treat certain diseases. iPS cells have the great advantage that they can easily be genetically manipulated rendering them ideal for treating monogenetic disorders when combined with cell transplantation-based therapies. In particular we are working on Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa in collaboration with Stanford's Dermatology Department. An exciting application of iN cell technology will be to try modeling neurological diseases in vitro. We perform both mouse and human experiments hoping to identify quantifiable phenotypes correlated with genotype and in a second step evaluate whether this assay could be used to discover novel drugs improve the disease progression.

Wernig Lab Research

Overview

Our lab is interested in the molecular mechanisms that define neural lineage identity focusing on transcription factors and chromatin biology. We use cellular reprogramming to understand how neurons are induced, how they mature and maintain their identity. Reprogramming also allows us to generate a novel tool box to study human neuronal and glial cell biology which become powerful human disease models in combination with genetic engineering. We further seek to develop reprogramming & genetic engineering approaches towards stem cell-based therapies. Finally, we study microglia-neuron interactions with the ultimate goal to understand the brain's immune system in health and disease and to exploit microglia for therapeutic and regenerative purposes.

Human neuronal cell disease modeling

Neurosychiatric diseases like autism and schizophrenia are highly complex brain disorders difficult to model in mice in part due to complex genetic etiology and sometimes affecting human-specific genes. We develop novel human cell models to investigate disease-relevant cell biological phenomena.

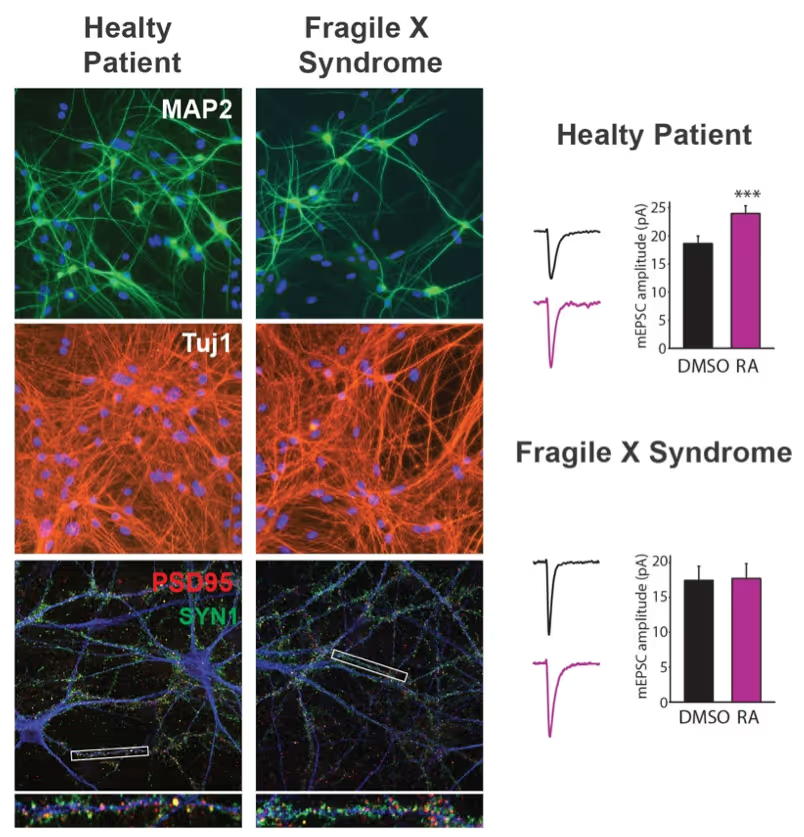

Generation of defined human neuronal cell types to study neuronal cell biology

We have and continue to develop protocols to generate specific types of neurons such as pure glutamatergic and pure GABAergic neurons from human pluripotent stem cells using transcription factors. In combination with genetic engineering or deriving iPS cells from patients, we then interrogate the cell biology of human neurons that carry disease-causing mutations. A particular focus is on synaptic function as shown in the figure on the right on Fragile X Syndrome neurons in collaboration with Lu Chen and Tom Südhof's laboratories.

Making neurons from blood

The ability to generate functional induced neuronal cells from distantly related somatic cell types is fascinating but also offers the opportunity to obtain neurons from a larger cohort of human subjects. In particular blood is readily available and we showed can be efficiently converted into functional neurons from young and aged donors.

Developing next generation cell therapies

The combination of reprogramming and gene editing is truly powerful as it provides exciting new possibilities to generate cells that can be transplanted and have disease modifying activity. We currently apply this approach to restore mono-genetic diseases, but our vision goes beyond simple regenerative medicine. We will be able to genetically engineer designer cells that functionally integrate into diseased tissue equipped with sensing and intelligent disease-response mechanisms.

Towards a Phase 1 clinical trial for the fatal skin disease Epidermolysis Bullosa

Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa is a severe, blistering monogenetic skin disease caused by mutations in the gene coding for type VII collagen. We have developed a 1-step gene editing/iPS cell reprogramming method to rapidly generate patient iPS cells corrected for their disease-causing mutations in the Collagen7a1 gene. In collaboration with dermatologist Tony Oro we are developing a cell manufacturing process compatible with Good Manufacturing Procedures (GMP) to obtain FDA-approval for a first in man Phase I clinical trial with with a genetically engineered iPS cell product.

Exploiting glia cell transplantation to treat neurodegenerative disease

Both oligodendrocyte precursor cells as well as microglia can efficiently repopulate the brain. We are interested in exploiting the properties of these cells to develop novel cell therapies for the brain either to use the transplanted cells to restore function such as myelination, to alter the function of transplanted cells for therepeutic benefit, to use the cells as vehicles for therapeutic molecules, or ultimately to develop designer cells that are engineered with genetic synthetic biology circuits to sense and interfere with disease processes of the brain.

Mechanisms of neural cell lineage identity

We are interested in the molecular mechanisms that define neuronal and glial cell identity. We found sets of transcription factors that can convert fibroblasts or lymphocytes into neurons and oligodendrocytes. These factors are also operational during normal development and are largely responsible to induce terminal lineages from progenitor cells.

"On target" pioneer factors and chromatin remodeling during neuronal induction

We found that Ascl1, one of our reprogramming factors, has a unique ability to access its physiological targets even in fibroblasts where these sites are in a closed chromatin configuration. We are fascinated by this "on target" pioneering property and are investigating how Ascl1 can access its target sites in an unfavorable chromatin environment and how it then remodels the chromatin at these sites to activate the neuronal transcriptional program.

Maintenance of neuronal identity

Once neurons are made, there ought to be also mechanisms that maintain neuronal identity. We stumbled upon a novel repressive mechanism: The neuronal-specific transcription factor Myt1l continuosly represses many non-neuronal programs in neurons leaving the neuronal program open to activate by other factors and thereby ensuring stable neuronal gene expression. Myt1l was also recently found to be mutated in autism and schizophrenia.

Microglia-neuron interactions in the healthy and diseased brain

Microglia, the brain's resident immune cells, are fascinating cells. They are derived from yolk sac progenitor cells early during development, are long-lived, and are not exchanged from bone marrow progenitor cells under physiological conditions. Microglia have been implicated in synaptic pruning, adult neurogenesis, and various brain diseases including Alzheimer's disease and Schizophrenia.

Developing an efficient microglia replacement system

We have developed a method to efficiently replace endogenous microglia from circulating cells without genetic manipulation. This does not happen physiologically but under certain conditions peripheral blood cells cross the blood-brain-barrier, migrate into the brain parenchyma and replace endogenous cells. We are investigating the cellular and molecular signals that enable circulating cells to invade the brain in order to further improve microglia replacement strategies.

The role of microglia in the normal and the diseased brain

Our ability to replace microglia provides us with a powerful tool to functionally perturb microglia function in normal and disease states. E.g. the microglial gene TREM2 is a strong Alzheimer's disease risk gene, but major questions about the neuro-immune interplay in the context of neurodegeneration and aging remain unsolved. Microglia replacement also provides an exciting prospect to develop novel cell therapies for a variety of brain diseases including enzyme deficiency syndromes, neurodegeneration, and brain tumors.

Lab Gene Expression Data

Publications

Citri A, Pang ZP, Südhof TC, Wernig M, Malenka RC

A major challenge in neuronal stem cell biology lies in characterization of lineage-specific reprogrammed human neuronal cells, a process that necessitates the use of an assay sensitive to the single-cell level. Single-cell gene profiling can provide definitive evidence regarding the conversion of one cell type into another at a high level of resolution. The protocol we describe uses Fluidigm Biomark dynamic arrays for high-throughput expression profiling from single neuronal cells, assaying up to 96 independent samples with up to 96 quantitative PCR (qPCR) probes (equivalent to 9,216 reactions) in a single experiment, which can be completed within 2-3 d. The protocol enables simple and cost-effective profiling of several hundred transcripts from a single cell, and it could have numerous utilities.

A major challenge in neuronal stem cell biology lies in characterization of lineage-specific reprogrammed human neuronal cells, a process that necessitates the use of an assay sensitive to the single-cell level. Single-cell gene profiling can provide definitive evidence regarding the conversion of one cell type into another at a high level of resolution. The protocol we describe uses Fluidigm Biomark dynamic arrays for high-throughput expression profiling from single neuronal cells, assaying up to 96 independent samples with up to 96 quantitative PCR (qPCR) probes (equivalent to 9,216 reactions) in a single experiment, which can be completed within 2-3 d. The protocol enables simple and cost-effective profiling of several hundred transcripts from a single cell, and it could have numerous utilities.

Ming GL, Brüstle O, Muotri A, Studer L, Wernig M, Christian KM

The remarkable advances in cellular reprogramming have made it possible to generate a renewable source of human neurons from fibroblasts obtained from skin samples of neonates and adults. As a result, we can now investigate the etiology of neurological diseases at the cellular level using neuronal populations derived from patients, which harbor the same genetic mutations thought to be relevant to the risk for pathology. Therapeutic implications include the ability to establish new humanized disease models for understanding mechanisms, conduct high-throughput screening for novel biogenic compounds to reverse or prevent the disease phenotype, identify and engineer genetic rescue of causal mutations, and develop patient-specific cellular replacement strategies. Although this field offers enormous potential for understanding and treating neurological disease, there are still many issues that must be addressed before we can fully exploit this technology. Here we summarize several recent studies presented at a symposium at the 2011 annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, which highlight innovative approaches to cellular reprogramming and how this revolutionary technique is being refined to model neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases, such as autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia, familial dysautonomia, and Alzheimer's disease.

The remarkable advances in cellular reprogramming have made it possible to generate a renewable source of human neurons from fibroblasts obtained from skin samples of neonates and adults. As a result, we can now investigate the etiology of neurological diseases at the cellular level using neuronal populations derived from patients, which harbor the same genetic mutations thought to be relevant to the risk for pathology. Therapeutic implications include the ability to establish new humanized disease models for understanding mechanisms, conduct high-throughput screening for novel biogenic compounds to reverse or prevent the disease phenotype, identify and engineer genetic rescue of causal mutations, and develop patient-specific cellular replacement strategies. Although this field offers enormous potential for understanding and treating neurological disease, there are still many issues that must be addressed before we can fully exploit this technology. Here we summarize several recent studies presented at a symposium at the 2011 annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, which highlight innovative approaches to cellular reprogramming and how this revolutionary technique is being refined to model neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases, such as autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia, familial dysautonomia, and Alzheimer's disease.

Elefanty AG, Blelloch R, Passegué E, Wernig M, Mummery CL

The 2010 Annual Meeting of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) was held in San Francisco in June with an exciting program covering a wealth of stem cell research from basic science to clinical research.

The 2010 Annual Meeting of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) was held in San Francisco in June with an exciting program covering a wealth of stem cell research from basic science to clinical research.

Carette JE, Pruszak J, Varadarajan M, Blomen VA, Gokhale S, Camargo FD, Wernig M, Jaenisch R, Brummelkamp TR

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can be generated from various differentiated cell types by the expression of a set of defined transcription factors. So far, iPSCs have been generated from primary cells, but it is unclear whether human cancer cell lines can be reprogrammed. Here we describe the generation and characterization of iPSCs derived from human chronic myeloid leukemia cells. We show that, despite the presence of oncogenic mutations, these cells acquired pluripotency by the expression of 4 transcription factors and underwent differentiation into cell types derived of all 3 germ layers during teratoma formation. Interestingly, although the parental cell line was strictly dependent on continuous signaling of the BCR-ABL oncogene, also termed oncogene addiction, reprogrammed cells lost this dependency and became resistant to the BCR-ABL inhibitor imatinib. This finding indicates that the therapeutic agent imatinib targets cells in a specific epigenetic differentiated cell state, and this may contribute to its inability to fully eradicate disease in chronic myeloid leukemia patients.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can be generated from various differentiated cell types by the expression of a set of defined transcription factors. So far, iPSCs have been generated from primary cells, but it is unclear whether human cancer cell lines can be reprogrammed. Here we describe the generation and characterization of iPSCs derived from human chronic myeloid leukemia cells. We show that, despite the presence of oncogenic mutations, these cells acquired pluripotency by the expression of 4 transcription factors and underwent differentiation into cell types derived of all 3 germ layers during teratoma formation. Interestingly, although the parental cell line was strictly dependent on continuous signaling of the BCR-ABL oncogene, also termed oncogene addiction, reprogrammed cells lost this dependency and became resistant to the BCR-ABL inhibitor imatinib. This finding indicates that the therapeutic agent imatinib targets cells in a specific epigenetic differentiated cell state, and this may contribute to its inability to fully eradicate disease in chronic myeloid leukemia patients.

Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Südhof TC, Wernig M

Cellular differentiation and lineage commitment are considered to be robust and irreversible processes during development. Recent work has shown that mouse and human fibroblasts can be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state with a combination of four transcription factors. This raised the question of whether transcription factors could directly induce other defined somatic cell fates, and not only an undifferentiated state. We hypothesized that combinatorial expression of neural-lineage-specific transcription factors could directly convert fibroblasts into neurons. Starting from a pool of nineteen candidate genes, we identified a combination of only three factors, Ascl1, Brn2 (also called Pou3f2) and Myt1l, that suffice to rapidly and efficiently convert mouse embryonic and postnatal fibroblasts into functional neurons in vitro. These induced neuronal (iN) cells express multiple neuron-specific proteins, generate action potentials and form functional synapses. Generation of iN cells from non-neural lineages could have important implications for studies of neural development, neurological disease modelling and regenerative medicine.

Cellular differentiation and lineage commitment are considered to be robust and irreversible processes during development. Recent work has shown that mouse and human fibroblasts can be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state with a combination of four transcription factors. This raised the question of whether transcription factors could directly induce other defined somatic cell fates, and not only an undifferentiated state. We hypothesized that combinatorial expression of neural-lineage-specific transcription factors could directly convert fibroblasts into neurons. Starting from a pool of nineteen candidate genes, we identified a combination of only three factors, Ascl1, Brn2 (also called Pou3f2) and Myt1l, that suffice to rapidly and efficiently convert mouse embryonic and postnatal fibroblasts into functional neurons in vitro. These induced neuronal (iN) cells express multiple neuron-specific proteins, generate action potentials and form functional synapses. Generation of iN cells from non-neural lineages could have important implications for studies of neural development, neurological disease modelling and regenerative medicine.

Xi J, Khalil M, Shishechian N, Hannes T, Pfannkuche K, Liang H, Fatima A, Haustein M, Suhr F, Bloch W, Reppel M, Sarić T, Wernig M, Jänisch R, Brockmeier K, Hescheler J, Pillekamp F

Cardiomyocytes generated from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells are suggested for repopulation of destroyed myocardium. Because contractile properties are crucial for functional regeneration, we compared cardiomyocytes differentiated from ES cells (ESC-CMs) and iPS cells (iPS-CMs). Native myocardium served as control. Murine ESCs or iPS cells were differentiated 11 d in vitro and cocultured 5-7 d with irreversibly injured myocardial tissue slices. Vital embryonic ventricular tissue slices of similar age served for comparison. Force-frequency relationship (FFR), effects of Ca(2+), Ni(2+), nifedipine, ryanodine, beta-adrenergic, and muscarinic modulation were studied during loaded contractions. FFR was negative for ESC-CMs and iPS-CMs. FFR was positive for embryonic tissue and turned negative after treatment with ryanodine. In all groups, force of contraction and relaxation time increased with the concentration of Ca(2+) and decreased with nifedipine. Force was reduced by Ni(2+). Isoproterenol (1 microM) increased the force most pronounced in embryonic tissue (207+/-31%, n=7; ESC-CMs: 123+/-5%, n=4; iPS-CMs: 120+/-4%, n=8). EC(50) values were similar. Contractile properties of iPS-CMs and ESC-CMs were similar, but they were significantly different from ventricular tissue of comparable age. The results indicate immaturity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum and the beta-adrenergic response of iPS-CMs and ESC-CMs.

Cardiomyocytes generated from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells are suggested for repopulation of destroyed myocardium. Because contractile properties are crucial for functional regeneration, we compared cardiomyocytes differentiated from ES cells (ESC-CMs) and iPS cells (iPS-CMs). Native myocardium served as control. Murine ESCs or iPS cells were differentiated 11 d in vitro and cocultured 5-7 d with irreversibly injured myocardial tissue slices. Vital embryonic ventricular tissue slices of similar age served for comparison. Force-frequency relationship (FFR), effects of Ca(2+), Ni(2+), nifedipine, ryanodine, beta-adrenergic, and muscarinic modulation were studied during loaded contractions. FFR was negative for ESC-CMs and iPS-CMs. FFR was positive for embryonic tissue and turned negative after treatment with ryanodine. In all groups, force of contraction and relaxation time increased with the concentration of Ca(2+) and decreased with nifedipine. Force was reduced by Ni(2+). Isoproterenol (1 microM) increased the force most pronounced in embryonic tissue (207+/-31%, n=7; ESC-CMs: 123+/-5%, n=4; iPS-CMs: 120+/-4%, n=8). EC(50) values were similar. Contractile properties of iPS-CMs and ESC-CMs were similar, but they were significantly different from ventricular tissue of comparable age. The results indicate immaturity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum and the beta-adrenergic response of iPS-CMs and ESC-CMs.

Kuzmenkin A, Liang H, Xu G, Pfannkuche K, Eichhorn H, Fatima A, Luo H, Saric T, Wernig M, Jaenisch R, Hescheler J

Several types of terminally differentiated somatic cells can be reprogrammed into a pluripotent state by ectopic expression of Klf4, Oct3/4, Sox2, and c-Myc. Such induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells have great potential to serve as an autologous source of cells for tissue repair. In the process of developing iPS-cell-based therapies, the major goal is to determine whether differentiated cells derived from iPS cells, such as cardiomyocytes (CMs), have the same functional properties as their physiological in vivo counterparts. Therefore, we differentiated murine iPS cells to CMs in vitro and characterized them by RT-PCR, immunocytochemistry, and electrophysiology. As key markers of cardiac lineages, transcripts for Nkx2.5, alphaMHC, Mlc2v, and cTnT could be identified. Immunocytochemical stainings revealed the presence of organized sarcomeric actinin but the absence of mature atrial natriuretic factor. We examined characteristics and developmental changes of action potentials, as well as functional hormonal regulation and sensitivity to channel blockers. In addition, we determined expression patterns and functionality of cardiac-specific voltage-gated Na+, Ca2+, and K+ channels at early and late differentiation stages and compared them with CMs derived from murine embryonic stem cells (ESCs) as well as with fetal CMs. We conclude that iPS cells give rise to functional CMs in vitro, with established hormonal regulation pathways and functionally expressed cardiac ion channels; CMs generated from iPS cells have a ventricular phenotype; and cardiac development of iPS cells is delayed compared with maturation of native fetal CMs and of ESC-derived CMs. This difference may reflect the incomplete reprogramming of iPS cells and should be critically considered in further studies to clarify the suitability of the iPS model for regenerative medicine of heart disorders.

Several types of terminally differentiated somatic cells can be reprogrammed into a pluripotent state by ectopic expression of Klf4, Oct3/4, Sox2, and c-Myc. Such induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells have great potential to serve as an autologous source of cells for tissue repair. In the process of developing iPS-cell-based therapies, the major goal is to determine whether differentiated cells derived from iPS cells, such as cardiomyocytes (CMs), have the same functional properties as their physiological in vivo counterparts. Therefore, we differentiated murine iPS cells to CMs in vitro and characterized them by RT-PCR, immunocytochemistry, and electrophysiology. As key markers of cardiac lineages, transcripts for Nkx2.5, alphaMHC, Mlc2v, and cTnT could be identified. Immunocytochemical stainings revealed the presence of organized sarcomeric actinin but the absence of mature atrial natriuretic factor. We examined characteristics and developmental changes of action potentials, as well as functional hormonal regulation and sensitivity to channel blockers. In addition, we determined expression patterns and functionality of cardiac-specific voltage-gated Na+, Ca2+, and K+ channels at early and late differentiation stages and compared them with CMs derived from murine embryonic stem cells (ESCs) as well as with fetal CMs. We conclude that iPS cells give rise to functional CMs in vitro, with established hormonal regulation pathways and functionally expressed cardiac ion channels; CMs generated from iPS cells have a ventricular phenotype; and cardiac development of iPS cells is delayed compared with maturation of native fetal CMs and of ESC-derived CMs. This difference may reflect the incomplete reprogramming of iPS cells and should be critically considered in further studies to clarify the suitability of the iPS model for regenerative medicine of heart disorders.

Pfannkuche K, Liang H, Hannes T, Xi J, Fatima A, Nguemo F, Matzkies M, Wernig M, Jaenisch R, Pillekamp F, Halbach M, Schunkert H, Sarić T, Hescheler J, Reppel M

AIMS: Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells have a developmental potential similar to that of blastocyst-derived embryonic stem (ES) cells and may serve as an autologous source of cells for tissue repair, in vitro disease modelling and toxicity assays. Here we aimed at generating iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes (CMs) and comparing their molecular and functional characteristics with CMs derived from native murine ES cells. METHODS AND RESULTS: Beating cardiomyocytes were generated using a mass culture system from murine N10 and O9 iPS cells as well as R1 and D3 ES cells. Transcripts of the mesoderm specification factor T-brachyury and non-atrial cardiac specific genes were expressed in differentiating iPS EBs. Using immunocytochemistry to determine the expression and intracellular organisation of cardiac specific structural proteins we demonstrate strong similarity between iPS-CMs and ES-CMs. In line with a previous study electrophysiological analyses showed that hormonal response to beta-adrenergic and muscarinic receptor stimulation was intact. Action potential (AP) recordings suggested that most iPS-CMs measured up to day 23 of differentiation are of ventricular-like type. Application of lidocaine, Cs+, SEA0400 and verapamil+ nifedipine to plated iPS-EBs during multi-electrode array (MEA) measurements of extracellular field potentials and intracellular sharp electrode recordings of APs revealed the presence of I(Na), I(f), I(NCX), and I(CaL), respectively, and suggested their involvement in cardiac pacemaking, with I(CaL) being of major importance. Furthermore, iPS-CMs developed and conferred force to avitalized ventricular tissue that was responsive to beta-adrenergic stimulation. CONCLUSIONS: Our data demonstrate that the cardiogenic potential of iPS cells is comparable to that of ES cells and that iPS-CMs possess all fundamental functional elements of a typical cardiac cell, including spontaneous beating, hormonal regulation, cardiac ion channel expression and contractility. Therefore, iPS-CMs can be regarded as a potentially valuable source of cells for in vitro studies and cellular cardiomyoplasty.

AIMS: Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells have a developmental potential similar to that of blastocyst-derived embryonic stem (ES) cells and may serve as an autologous source of cells for tissue repair, in vitro disease modelling and toxicity assays. Here we aimed at generating iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes (CMs) and comparing their molecular and functional characteristics with CMs derived from native murine ES cells. METHODS AND RESULTS: Beating cardiomyocytes were generated using a mass culture system from murine N10 and O9 iPS cells as well as R1 and D3 ES cells. Transcripts of the mesoderm specification factor T-brachyury and non-atrial cardiac specific genes were expressed in differentiating iPS EBs. Using immunocytochemistry to determine the expression and intracellular organisation of cardiac specific structural proteins we demonstrate strong similarity between iPS-CMs and ES-CMs. In line with a previous study electrophysiological analyses showed that hormonal response to beta-adrenergic and muscarinic receptor stimulation was intact. Action potential (AP) recordings suggested that most iPS-CMs measured up to day 23 of differentiation are of ventricular-like type. Application of lidocaine, Cs+, SEA0400 and verapamil+ nifedipine to plated iPS-EBs during multi-electrode array (MEA) measurements of extracellular field potentials and intracellular sharp electrode recordings of APs revealed the presence of I(Na), I(f), I(NCX), and I(CaL), respectively, and suggested their involvement in cardiac pacemaking, with I(CaL) being of major importance. Furthermore, iPS-CMs developed and conferred force to avitalized ventricular tissue that was responsive to beta-adrenergic stimulation. CONCLUSIONS: Our data demonstrate that the cardiogenic potential of iPS cells is comparable to that of ES cells and that iPS-CMs possess all fundamental functional elements of a typical cardiac cell, including spontaneous beating, hormonal regulation, cardiac ion channel expression and contractility. Therefore, iPS-CMs can be regarded as a potentially valuable source of cells for in vitro studies and cellular cardiomyoplasty.

Brambrink T, Foreman R, Welstead GG, Lengner CJ, Wernig M, Suh H, Jaenisch R

Pluripotency can be induced in differentiated murine and human cells by retroviral transduction of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc. We have devised a reprogramming strategy in which these four transcription factors are expressed from doxycycline (dox)-inducible lentiviral vectors. Using these inducible constructs, we derived induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and found that transgene silencing is a prerequisite for normal cell differentiation. We have analyzed the timing of known pluripotency marker activation during mouse iPS cell derivation and observed that alkaline phosphatase (AP) was activated first, followed by stage-specific embryonic antigen 1 (SSEA1). Expression of Nanog and the endogenous Oct4 gene, marking fully reprogrammed cells, was only observed late in the process. Importantly, the virally transduced cDNAs needed to be expressed for at least 12 days in order to generate iPS cells. Our results are a step toward understanding some of the molecular events governing epigenetic reprogramming.

Pluripotency can be induced in differentiated murine and human cells by retroviral transduction of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc. We have devised a reprogramming strategy in which these four transcription factors are expressed from doxycycline (dox)-inducible lentiviral vectors. Using these inducible constructs, we derived induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and found that transgene silencing is a prerequisite for normal cell differentiation. We have analyzed the timing of known pluripotency marker activation during mouse iPS cell derivation and observed that alkaline phosphatase (AP) was activated first, followed by stage-specific embryonic antigen 1 (SSEA1). Expression of Nanog and the endogenous Oct4 gene, marking fully reprogrammed cells, was only observed late in the process. Importantly, the virally transduced cDNAs needed to be expressed for at least 12 days in order to generate iPS cells. Our results are a step toward understanding some of the molecular events governing epigenetic reprogramming.

Wernig M, Zhao JP, Pruszak J, Hedlund E, Fu D, Soldner F, Broccoli V, Constantine-Paton M, Isacson O, Jaenisch R

The long-term goal of nuclear transfer or alternative reprogramming approaches is to create patient-specific donor cells for transplantation therapy, avoiding immunorejection, a major complication in current transplantation medicine. It was recently shown that the four transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc induce pluripotency in mouse fibroblasts. However, the therapeutic potential of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells for neural cell replacement strategies remained unexplored. Here, we show that iPS cells can be efficiently differentiated into neural precursor cells, giving rise to neuronal and glial cell types in culture. Upon transplantation into the fetal mouse brain, the cells migrate into various brain regions and differentiate into glia and neurons, including glutamatergic, GABAergic, and catecholaminergic subtypes. Electrophysiological recordings and morphological analysis demonstrated that the grafted neurons had mature neuronal activity and were functionally integrated in the host brain. Furthermore, iPS cells were induced to differentiate into dopamine neurons of midbrain character and were able to improve behavior in a rat model of Parkinson's disease upon transplantation into the adult brain. We minimized the risk of tumor formation from the grafted cells by separating contaminating pluripotent cells and committed neural cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Our results demonstrate the therapeutic potential of directly reprogrammed fibroblasts for neuronal cell replacement in the animal model.

The long-term goal of nuclear transfer or alternative reprogramming approaches is to create patient-specific donor cells for transplantation therapy, avoiding immunorejection, a major complication in current transplantation medicine. It was recently shown that the four transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc induce pluripotency in mouse fibroblasts. However, the therapeutic potential of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells for neural cell replacement strategies remained unexplored. Here, we show that iPS cells can be efficiently differentiated into neural precursor cells, giving rise to neuronal and glial cell types in culture. Upon transplantation into the fetal mouse brain, the cells migrate into various brain regions and differentiate into glia and neurons, including glutamatergic, GABAergic, and catecholaminergic subtypes. Electrophysiological recordings and morphological analysis demonstrated that the grafted neurons had mature neuronal activity and were functionally integrated in the host brain. Furthermore, iPS cells were induced to differentiate into dopamine neurons of midbrain character and were able to improve behavior in a rat model of Parkinson's disease upon transplantation into the adult brain. We minimized the risk of tumor formation from the grafted cells by separating contaminating pluripotent cells and committed neural cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Our results demonstrate the therapeutic potential of directly reprogrammed fibroblasts for neuronal cell replacement in the animal model.

Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Wernig M, Hanna J, Sivachenko A, Zhang X, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Jaffe DB, Gnirke A, Jaenisch R, Lander ES

DNA methylation is essential for normal development and has been implicated in many pathologies including cancer. Our knowledge about the genome-wide distribution of DNA methylation, how it changes during cellular differentiation and how it relates to histone methylation and other chromatin modifications in mammals remains limited. Here we report the generation and analysis of genome-scale DNA methylation profiles at nucleotide resolution in mammalian cells. Using high-throughput reduced representation bisulphite sequencing and single-molecule-based sequencing, we generated DNA methylation maps covering most CpG islands, and a representative sampling of conserved non-coding elements, transposons and other genomic features, for mouse embryonic stem cells, embryonic-stem-cell-derived and primary neural cells, and eight other primary tissues. Several key findings emerge from the data. First, DNA methylation patterns are better correlated with histone methylation patterns than with the underlying genome sequence context. Second, methylation of CpGs are dynamic epigenetic marks that undergo extensive changes during cellular differentiation, particularly in regulatory regions outside of core promoters. Third, analysis of embryonic-stem-cell-derived and primary cells reveals that 'weak' CpG islands associated with a specific set of developmentally regulated genes undergo aberrant hypermethylation during extended proliferation in vitro, in a pattern reminiscent of that reported in some primary tumours. More generally, the results establish reduced representation bisulphite sequencing as a powerful technology for epigenetic profiling of cell populations relevant to developmental biology, cancer and regenerative medicine.

DNA methylation is essential for normal development and has been implicated in many pathologies including cancer. Our knowledge about the genome-wide distribution of DNA methylation, how it changes during cellular differentiation and how it relates to histone methylation and other chromatin modifications in mammals remains limited. Here we report the generation and analysis of genome-scale DNA methylation profiles at nucleotide resolution in mammalian cells. Using high-throughput reduced representation bisulphite sequencing and single-molecule-based sequencing, we generated DNA methylation maps covering most CpG islands, and a representative sampling of conserved non-coding elements, transposons and other genomic features, for mouse embryonic stem cells, embryonic-stem-cell-derived and primary neural cells, and eight other primary tissues. Several key findings emerge from the data. First, DNA methylation patterns are better correlated with histone methylation patterns than with the underlying genome sequence context. Second, methylation of CpGs are dynamic epigenetic marks that undergo extensive changes during cellular differentiation, particularly in regulatory regions outside of core promoters. Third, analysis of embryonic-stem-cell-derived and primary cells reveals that 'weak' CpG islands associated with a specific set of developmentally regulated genes undergo aberrant hypermethylation during extended proliferation in vitro, in a pattern reminiscent of that reported in some primary tumours. More generally, the results establish reduced representation bisulphite sequencing as a powerful technology for epigenetic profiling of cell populations relevant to developmental biology, cancer and regenerative medicine.

Mikkelsen TS, Hanna J, Zhang X, Ku M, Wernig M, Schorderet P, Bernstein BE, Jaenisch R, Lander ES, Meissner A

Somatic cells can be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state through the ectopic expression of defined transcription factors. Understanding the mechanism and kinetics of this transformation may shed light on the nature of developmental potency and suggest strategies with improved efficiency or safety. Here we report an integrative genomic analysis of reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts and B lymphocytes. Lineage-committed cells show a complex response to the ectopic expression involving induction of genes downstream of individual reprogramming factors. Fully reprogrammed cells show gene expression and epigenetic states that are highly similar to embryonic stem cells. In contrast, stable partially reprogrammed cell lines show reactivation of a distinctive subset of stem-cell-related genes, incomplete repression of lineage-specifying transcription factors, and DNA hypermethylation at pluripotency-related loci. These observations suggest that some cells may become trapped in partially reprogrammed states owing to incomplete repression of transcription factors, and that DNA de-methylation is an inefficient step in the transition to pluripotency. We demonstrate that RNA inhibition of transcription factors can facilitate reprogramming, and that treatment with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors can improve the overall efficiency of the reprogramming process.

Somatic cells can be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state through the ectopic expression of defined transcription factors. Understanding the mechanism and kinetics of this transformation may shed light on the nature of developmental potency and suggest strategies with improved efficiency or safety. Here we report an integrative genomic analysis of reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts and B lymphocytes. Lineage-committed cells show a complex response to the ectopic expression involving induction of genes downstream of individual reprogramming factors. Fully reprogrammed cells show gene expression and epigenetic states that are highly similar to embryonic stem cells. In contrast, stable partially reprogrammed cell lines show reactivation of a distinctive subset of stem-cell-related genes, incomplete repression of lineage-specifying transcription factors, and DNA hypermethylation at pluripotency-related loci. These observations suggest that some cells may become trapped in partially reprogrammed states owing to incomplete repression of transcription factors, and that DNA de-methylation is an inefficient step in the transition to pluripotency. We demonstrate that RNA inhibition of transcription factors can facilitate reprogramming, and that treatment with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors can improve the overall efficiency of the reprogramming process.

Hanna J, Markoulaki S, Schorderet P, Carey BW, Beard C, Wernig M, Creyghton MP, Steine EJ, Cassady JP, Foreman R, Lengner CJ, Dausman JA, Jaenisch R

Pluripotent cells can be derived from fibroblasts by ectopic expression of defined transcription factors. A fundamental unresolved question is whether terminally differentiated cells can be reprogrammed to pluripotency. We utilized transgenic and inducible expression of four transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) to reprogram mouse B lymphocytes. These factors were sufficient to convert nonterminally differentiated B cells to a pluripotent state. However, reprogramming of mature B cells required additional interruption with the transcriptional state maintaining B cell identity by either ectopic expression of the myeloid transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding-protein-alpha (C/EBPalpha) or specific knockdown of the B cell transcription factor Pax5. Multiple iPS lines were clonally derived from both nonfully and fully differentiated B lymphocytes, which gave rise to adult chimeras with germline contribution, and to late-term embryos when injected into tetraploid blastocysts. Our study provides definite proof for the direct nuclear reprogramming of terminally differentiated adult cells to pluripotency.

Pluripotent cells can be derived from fibroblasts by ectopic expression of defined transcription factors. A fundamental unresolved question is whether terminally differentiated cells can be reprogrammed to pluripotency. We utilized transgenic and inducible expression of four transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) to reprogram mouse B lymphocytes. These factors were sufficient to convert nonterminally differentiated B cells to a pluripotent state. However, reprogramming of mature B cells required additional interruption with the transcriptional state maintaining B cell identity by either ectopic expression of the myeloid transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding-protein-alpha (C/EBPalpha) or specific knockdown of the B cell transcription factor Pax5. Multiple iPS lines were clonally derived from both nonfully and fully differentiated B lymphocytes, which gave rise to adult chimeras with germline contribution, and to late-term embryos when injected into tetraploid blastocysts. Our study provides definite proof for the direct nuclear reprogramming of terminally differentiated adult cells to pluripotency.

Marson A, Levine SS, Cole MF, Frampton GM, Brambrink T, Johnstone S, Guenther MG, Johnston WK, Wernig M, Newman J, Calabrese JM, Dennis LM, Volkert TL, Gupta S, Love J, Hannett N, Sharp PA, Bartel DP, Jaenisch R, Young RA

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are crucial for normal embryonic stem (ES) cell self-renewal and cellular differentiation, but how miRNA gene expression is controlled by the key transcriptional regulators of ES cells has not been established. We describe here the transcriptional regulatory circuitry of ES cells that incorporates protein-coding and miRNA genes based on high-resolution ChIP-seq data, systematic identification of miRNA promoters, and quantitative sequencing of short transcripts in multiple cell types. We find that the key ES cell transcription factors are associated with promoters for miRNAs that are preferentially expressed in ES cells and with promoters for a set of silent miRNA genes. This silent set of miRNA genes is co-occupied by Polycomb group proteins in ES cells and shows tissue-specific expression in differentiated cells. These data reveal how key ES cell transcription factors promote the ES cell miRNA expression program and integrate miRNAs into the regulatory circuitry controlling ES cell identity.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are crucial for normal embryonic stem (ES) cell self-renewal and cellular differentiation, but how miRNA gene expression is controlled by the key transcriptional regulators of ES cells has not been established. We describe here the transcriptional regulatory circuitry of ES cells that incorporates protein-coding and miRNA genes based on high-resolution ChIP-seq data, systematic identification of miRNA promoters, and quantitative sequencing of short transcripts in multiple cell types. We find that the key ES cell transcription factors are associated with promoters for miRNAs that are preferentially expressed in ES cells and with promoters for a set of silent miRNA genes. This silent set of miRNA genes is co-occupied by Polycomb group proteins in ES cells and shows tissue-specific expression in differentiated cells. These data reveal how key ES cell transcription factors promote the ES cell miRNA expression program and integrate miRNAs into the regulatory circuitry controlling ES cell identity.

Wernig M, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Jaenisch R

Wernig M, Lengner CJ, Hanna J, Lodato MA, Steine E, Foreman R, Staerk J, Markoulaki S, Jaenisch R

The study of induced pluripotency is complicated by the need for infection with high-titer retroviral vectors, which results in genetically heterogeneous cell populations. We generated genetically homogeneous 'secondary' somatic cells that carry the reprogramming factors as defined doxycycline (dox)-inducible transgenes. These cells were produced by infecting fibroblasts with dox-inducible lentiviruses, reprogramming by dox addition, selecting induced pluripotent stem cells and producing chimeric mice. Cells derived from these chimeras reprogram upon dox exposure without the need for viral infection with efficiencies 25- to 50-fold greater than those observed using direct infection and drug selection for pluripotency marker reactivation. We demonstrate that (i) various induction levels of the reprogramming factors can induce pluripotency, (ii) the duration of transgene activity directly correlates with reprogramming efficiency, (iii) cells from many somatic tissues can be reprogrammed and (iv) different cell types require different induction levels. This system facilitates the characterization of reprogramming and provides a tool for genetic or chemical screens to enhance reprogramming.

The study of induced pluripotency is complicated by the need for infection with high-titer retroviral vectors, which results in genetically heterogeneous cell populations. We generated genetically homogeneous 'secondary' somatic cells that carry the reprogramming factors as defined doxycycline (dox)-inducible transgenes. These cells were produced by infecting fibroblasts with dox-inducible lentiviruses, reprogramming by dox addition, selecting induced pluripotent stem cells and producing chimeric mice. Cells derived from these chimeras reprogram upon dox exposure without the need for viral infection with efficiencies 25- to 50-fold greater than those observed using direct infection and drug selection for pluripotency marker reactivation. We demonstrate that (i) various induction levels of the reprogramming factors can induce pluripotency, (ii) the duration of transgene activity directly correlates with reprogramming efficiency, (iii) cells from many somatic tissues can be reprogrammed and (iv) different cell types require different induction levels. This system facilitates the characterization of reprogramming and provides a tool for genetic or chemical screens to enhance reprogramming.

Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, Sun CW, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Beard C, Brambrink T, Wu LC, Townes TM, Jaenisch R

It has recently been demonstrated that mouse and human fibroblasts can be reprogrammed into an embryonic stem cell-like state by introducing combinations of four transcription factors. However, the therapeutic potential of such induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells remained undefined. By using a humanized sickle cell anemia mouse model, we show that mice can be rescued after transplantation with hematopoietic progenitors obtained in vitro from autologous iPS cells. This was achieved after correction of the human sickle hemoglobin allele by gene-specific targeting. Our results provide proof of principle for using transcription factor-induced reprogramming combined with gene and cell therapy for disease treatment in mice. The problems associated with using retroviruses and oncogenes for reprogramming need to be resolved before iPS cells can be considered for human therapy.

It has recently been demonstrated that mouse and human fibroblasts can be reprogrammed into an embryonic stem cell-like state by introducing combinations of four transcription factors. However, the therapeutic potential of such induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells remained undefined. By using a humanized sickle cell anemia mouse model, we show that mice can be rescued after transplantation with hematopoietic progenitors obtained in vitro from autologous iPS cells. This was achieved after correction of the human sickle hemoglobin allele by gene-specific targeting. Our results provide proof of principle for using transcription factor-induced reprogramming combined with gene and cell therapy for disease treatment in mice. The problems associated with using retroviruses and oncogenes for reprogramming need to be resolved before iPS cells can be considered for human therapy.

Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, Brambrink T, Ku M, Hochedlinger K, Bernstein BE, Jaenisch R

Nuclear transplantation can reprogramme a somatic genome back into an embryonic epigenetic state, and the reprogrammed nucleus can create a cloned animal or produce pluripotent embryonic stem cells. One potential use of the nuclear cloning approach is the derivation of 'customized' embryonic stem (ES) cells for patient-specific cell treatment, but technical and ethical considerations impede the therapeutic application of this technology. Reprogramming of fibroblasts to a pluripotent state can be induced in vitro through ectopic expression of the four transcription factors Oct4 (also called Oct3/4 or Pou5f1), Sox2, c-Myc and Klf4. Here we show that DNA methylation, gene expression and chromatin state of such induced reprogrammed stem cells are similar to those of ES cells. Notably, the cells-derived from mouse fibroblasts-can form viable chimaeras, can contribute to the germ line and can generate live late-term embryos when injected into tetraploid blastocysts. Our results show that the biological potency and epigenetic state of in-vitro-reprogrammed induced pluripotent stem cells are indistinguishable from those of ES cells.

Nuclear transplantation can reprogramme a somatic genome back into an embryonic epigenetic state, and the reprogrammed nucleus can create a cloned animal or produce pluripotent embryonic stem cells. One potential use of the nuclear cloning approach is the derivation of 'customized' embryonic stem (ES) cells for patient-specific cell treatment, but technical and ethical considerations impede the therapeutic application of this technology. Reprogramming of fibroblasts to a pluripotent state can be induced in vitro through ectopic expression of the four transcription factors Oct4 (also called Oct3/4 or Pou5f1), Sox2, c-Myc and Klf4. Here we show that DNA methylation, gene expression and chromatin state of such induced reprogrammed stem cells are similar to those of ES cells. Notably, the cells-derived from mouse fibroblasts-can form viable chimaeras, can contribute to the germ line and can generate live late-term embryos when injected into tetraploid blastocysts. Our results show that the biological potency and epigenetic state of in-vitro-reprogrammed induced pluripotent stem cells are indistinguishable from those of ES cells.

Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, Issac B, Lieberman E, Giannoukos G, Alvarez P, Brockman W, Kim TK, Koche RP, Lee W, Mendenhall E, O'Donovan A, Presser A, Russ C, Xie X, Meissner A, Wernig M, Jaenisch R, Nusbaum C, Lander ES, Bernstein BE

We report the application of single-molecule-based sequencing technology for high-throughput profiling of histone modifications in mammalian cells. By obtaining over four billion bases of sequence from chromatin immunoprecipitated DNA, we generated genome-wide chromatin-state maps of mouse embryonic stem cells, neural progenitor cells and embryonic fibroblasts. We find that lysine 4 and lysine 27 trimethylation effectively discriminates genes that are expressed, poised for expression, or stably repressed, and therefore reflect cell state and lineage potential. Lysine 36 trimethylation marks primary coding and non-coding transcripts, facilitating gene annotation. Trimethylation of lysine 9 and lysine 20 is detected at satellite, telomeric and active long-terminal repeats, and can spread into proximal unique sequences. Lysine 4 and lysine 9 trimethylation marks imprinting control regions. Finally, we show that chromatin state can be read in an allele-specific manner by using single nucleotide polymorphisms. This study provides a framework for the application of comprehensive chromatin profiling towards characterization of diverse mammalian cell populations.

We report the application of single-molecule-based sequencing technology for high-throughput profiling of histone modifications in mammalian cells. By obtaining over four billion bases of sequence from chromatin immunoprecipitated DNA, we generated genome-wide chromatin-state maps of mouse embryonic stem cells, neural progenitor cells and embryonic fibroblasts. We find that lysine 4 and lysine 27 trimethylation effectively discriminates genes that are expressed, poised for expression, or stably repressed, and therefore reflect cell state and lineage potential. Lysine 36 trimethylation marks primary coding and non-coding transcripts, facilitating gene annotation. Trimethylation of lysine 9 and lysine 20 is detected at satellite, telomeric and active long-terminal repeats, and can spread into proximal unique sequences. Lysine 4 and lysine 9 trimethylation marks imprinting control regions. Finally, we show that chromatin state can be read in an allele-specific manner by using single nucleotide polymorphisms. This study provides a framework for the application of comprehensive chromatin profiling towards characterization of diverse mammalian cell populations.

Meissner A, Wernig M, Jaenisch R

In vitro reprogramming of somatic cells into a pluripotent embryonic stem cell-like state has been achieved through retroviral transduction of murine fibroblasts with Oct4, Sox2, c-myc and Klf4. In these experiments, the rare 'induced pluripotent stem' (iPS) cells were isolated by stringent selection for activation of a neomycin-resistance gene inserted into the endogenous Oct4 (also known as Pou5f1) or Nanog loci. Direct isolation of pluripotent cells from cultured somatic cells is of potential therapeutic interest, but translation to human systems would be hindered by the requirement for transgenic donors in the present iPS isolation protocol. Here we demonstrate that reprogrammed pluripotent cells can be isolated from genetically unmodified somatic donor cells solely based upon morphological criteria.

In vitro reprogramming of somatic cells into a pluripotent embryonic stem cell-like state has been achieved through retroviral transduction of murine fibroblasts with Oct4, Sox2, c-myc and Klf4. In these experiments, the rare 'induced pluripotent stem' (iPS) cells were isolated by stringent selection for activation of a neomycin-resistance gene inserted into the endogenous Oct4 (also known as Pou5f1) or Nanog loci. Direct isolation of pluripotent cells from cultured somatic cells is of potential therapeutic interest, but translation to human systems would be hindered by the requirement for transgenic donors in the present iPS isolation protocol. Here we demonstrate that reprogrammed pluripotent cells can be isolated from genetically unmodified somatic donor cells solely based upon morphological criteria.

Boyer LA, Plath K, Zeitlinger J, Brambrink T, Medeiros LA, Lee TI, Levine SS, Wernig M, Tajonar A, Ray MK, Bell GW, Otte AP, Vidal M, Gifford DK, Young RA, Jaenisch R

The mechanisms by which embryonic stem (ES) cells self-renew while maintaining the ability to differentiate into virtually all adult cell types are not well understood. Polycomb group (PcG) proteins are transcriptional repressors that help to maintain cellular identity during metazoan development by epigenetic modification of chromatin structure. PcG proteins have essential roles in early embryonic development and have been implicated in ES cell pluripotency, but few of their target genes are known in mammals. Here we show that PcG proteins directly repress a large cohort of developmental regulators in murine ES cells, the expression of which would otherwise promote differentiation. Using genome-wide location analysis in murine ES cells, we found that the Polycomb repressive complexes PRC1 and PRC2 co-occupied 512 genes, many of which encode transcription factors with important roles in development. All of the co-occupied genes contained modified nucleosomes (trimethylated Lys 27 on histone H3). Consistent with a causal role in gene silencing in ES cells, PcG target genes were de-repressed in cells deficient for the PRC2 component Eed, and were preferentially activated on induction of differentiation. Our results indicate that dynamic repression of developmental pathways by Polycomb complexes may be required for maintaining ES cell pluripotency and plasticity during embryonic development.

The mechanisms by which embryonic stem (ES) cells self-renew while maintaining the ability to differentiate into virtually all adult cell types are not well understood. Polycomb group (PcG) proteins are transcriptional repressors that help to maintain cellular identity during metazoan development by epigenetic modification of chromatin structure. PcG proteins have essential roles in early embryonic development and have been implicated in ES cell pluripotency, but few of their target genes are known in mammals. Here we show that PcG proteins directly repress a large cohort of developmental regulators in murine ES cells, the expression of which would otherwise promote differentiation. Using genome-wide location analysis in murine ES cells, we found that the Polycomb repressive complexes PRC1 and PRC2 co-occupied 512 genes, many of which encode transcription factors with important roles in development. All of the co-occupied genes contained modified nucleosomes (trimethylated Lys 27 on histone H3). Consistent with a causal role in gene silencing in ES cells, PcG target genes were de-repressed in cells deficient for the PRC2 component Eed, and were preferentially activated on induction of differentiation. Our results indicate that dynamic repression of developmental pathways by Polycomb complexes may be required for maintaining ES cell pluripotency and plasticity during embryonic development.

Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, Jaenisch R, Wagschal A, Feil R, Schreiber SL, Lander ES

The most highly conserved noncoding elements (HCNEs) in mammalian genomes cluster within regions enriched for genes encoding developmentally important transcription factors (TFs). This suggests that HCNE-rich regions may contain key regulatory controls involved in development. We explored this by examining histone methylation in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells across 56 large HCNE-rich loci. We identified a specific modification pattern, termed "bivalent domains," consisting of large regions of H3 lysine 27 methylation harboring smaller regions of H3 lysine 4 methylation. Bivalent domains tend to coincide with TF genes expressed at low levels. We propose that bivalent domains silence developmental genes in ES cells while keeping them poised for activation. We also found striking correspondences between genome sequence and histone methylation in ES cells, which become notably weaker in differentiated cells. These results highlight the importance of DNA sequence in defining the initial epigenetic landscape and suggest a novel chromatin-based mechanism for maintaining pluripotency.

The most highly conserved noncoding elements (HCNEs) in mammalian genomes cluster within regions enriched for genes encoding developmentally important transcription factors (TFs). This suggests that HCNE-rich regions may contain key regulatory controls involved in development. We explored this by examining histone methylation in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells across 56 large HCNE-rich loci. We identified a specific modification pattern, termed "bivalent domains," consisting of large regions of H3 lysine 27 methylation harboring smaller regions of H3 lysine 4 methylation. Bivalent domains tend to coincide with TF genes expressed at low levels. We propose that bivalent domains silence developmental genes in ES cells while keeping them poised for activation. We also found striking correspondences between genome sequence and histone methylation in ES cells, which become notably weaker in differentiated cells. These results highlight the importance of DNA sequence in defining the initial epigenetic landscape and suggest a novel chromatin-based mechanism for maintaining pluripotency.

Wernig G, Janzen V, Schäfer R, Zweyer M, Knauf U, Hoegemeier O, Mundegar RR, Garbe S, Stier S, Franz T, Wernig M, Wernig A

Bone-marrow-derived cells can contribute nuclei to skeletal muscle fibers. However, serial sectioning of muscle in mdx mice implanted with GFP-labeled bone marrow reveals that only 20% of the donor nuclei chronically incorporated in muscle fibers show dystrophin (or GFP) expression, which is still higher than the expected frequency of "revertant" fibers, but there is no overall increase above controls over time. Obviously, the vast majority of incorporated nuclei either never or only temporarily turn on myogenic genes; also, incorporated nuclei eventually loose the activation of the beta-actin::GFP transgene. Consequently, we attempted to enhance the expression of dystrophin. In vivo application of the chromatin-modifying agents 5-azadeoxycytidine and phenylbutyrate as well as local damage by cardiotoxin injections caused a small increase in dystrophin-positive fibers without abolishing the appearance of "silent" nuclei. The results thus confirm that endogenous repair processes and epigenetic modifications on a small-scale lead to dystrophin expression from donor nuclei. Both effects, however, remain below functionally significant levels.

Bone-marrow-derived cells can contribute nuclei to skeletal muscle fibers. However, serial sectioning of muscle in mdx mice implanted with GFP-labeled bone marrow reveals that only 20% of the donor nuclei chronically incorporated in muscle fibers show dystrophin (or GFP) expression, which is still higher than the expected frequency of "revertant" fibers, but there is no overall increase above controls over time. Obviously, the vast majority of incorporated nuclei either never or only temporarily turn on myogenic genes; also, incorporated nuclei eventually loose the activation of the beta-actin::GFP transgene. Consequently, we attempted to enhance the expression of dystrophin. In vivo application of the chromatin-modifying agents 5-azadeoxycytidine and phenylbutyrate as well as local damage by cardiotoxin injections caused a small increase in dystrophin-positive fibers without abolishing the appearance of "silent" nuclei. The results thus confirm that endogenous repair processes and epigenetic modifications on a small-scale lead to dystrophin expression from donor nuclei. Both effects, however, remain below functionally significant levels.

Wernig M, Benninger F, Schmandt T, Rade M, Tucker KL, Büssow H, Beck H, Brüstle O

Pluripotency and the potential for continuous self-renewal make embryonic stem (ES) cells an attractive donor source for neuronal cell replacement. Despite recent encouraging results in this field, little is known about the functional integration of transplanted ES cell-derived neurons on the single-cell level. To address this issue, ES cell-derived neural precursors exhibiting neuron-specific enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression were introduced into the developing brain. Donor cells implanted into the cerebral ventricles of embryonic rats migrated as single cells into a variety of brain regions, where they acquired complex morphologies and adopted excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter phenotypes. Synaptic integration was suggested by the expression of PSD-95 (postsynaptic density-95) on donor cell dendrites, which in turn were approached by multiple synaptophysin-positive host axon terminals. Ultrastructural and electrophysiological data confirmed the formation of synapses between host and donor cells. Ten to 21 d after birth, all EGFP-positive donor cells examined displayed active membrane properties and received glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic input from host neurons. These data demonstrate that, at the single-cell level, grafted ES cell-derived neurons undergo morphological and functional integration into the host brain circuitry. Antibodies to the region-specific transcription factors Bf1, Dlx, En1, and Pax6 were used to explore whether functional donor cell integration depends on the acquisition of a regional phenotype. Our data show that incorporated neurons frequently exhibit a lacking or ectopic expression of these transcription factors. Thus, the lack of an appropriate regional "code" does not preclude morphological and synaptic integration of ES cell-derived neurons.

Pluripotency and the potential for continuous self-renewal make embryonic stem (ES) cells an attractive donor source for neuronal cell replacement. Despite recent encouraging results in this field, little is known about the functional integration of transplanted ES cell-derived neurons on the single-cell level. To address this issue, ES cell-derived neural precursors exhibiting neuron-specific enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression were introduced into the developing brain. Donor cells implanted into the cerebral ventricles of embryonic rats migrated as single cells into a variety of brain regions, where they acquired complex morphologies and adopted excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter phenotypes. Synaptic integration was suggested by the expression of PSD-95 (postsynaptic density-95) on donor cell dendrites, which in turn were approached by multiple synaptophysin-positive host axon terminals. Ultrastructural and electrophysiological data confirmed the formation of synapses between host and donor cells. Ten to 21 d after birth, all EGFP-positive donor cells examined displayed active membrane properties and received glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic input from host neurons. These data demonstrate that, at the single-cell level, grafted ES cell-derived neurons undergo morphological and functional integration into the host brain circuitry. Antibodies to the region-specific transcription factors Bf1, Dlx, En1, and Pax6 were used to explore whether functional donor cell integration depends on the acquisition of a regional phenotype. Our data show that incorporated neurons frequently exhibit a lacking or ectopic expression of these transcription factors. Thus, the lack of an appropriate regional "code" does not preclude morphological and synaptic integration of ES cell-derived neurons.

Marius Wernig

wernig@stanford.edu

Dr. Marius Wernig is a Professor of Pathology and a Co-Director of the Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine at Stanford University. He graduated with an M.D. Ph.D. from the Technical University of Munich where he trained in developmental genetics in the lab of Rudi Balling. After completing his residency in Neuropathology and General Pathology at the University of Bonn, he then became a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Dr. Rudolf Jaenisch at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research/ MIT in Cambridge, MA. In 2008, Dr. Wernig joined the faculty of the Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine at Stanford University where he has been ever since.

He received an NIH Pathway to Independence Award, the Cozzarelli Prize for Outstanding Scientific Excellence from the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A., the Outstanding Investigator Award from the International Society for Stem Cell Research, the New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Stem Cell Prize, the Ogawa-Yamanaka Stem Cell Prize delivered by the Gladstone Institute and more recently has been named a Faculty Scholar by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Dr. Wernig’s lab is interested in pluripotent stem cell biology and the molecular determinants of neural cell fate decisions. His laboratory was the first to generate functional neuronal cells reprogrammed directly from skin fibroblasts, which he termed induced neuronal (iN) cells. The lab is now working on identifying the molecular mechanisms underlying induced lineage fate changes, the phenotypic consequences of disease-causing mutations in human neurons and other neural lineages as well as the development of novel therapeutic gene targeting and cell transplantation-based strategies for a variety of monogenetic diseases.

Academic appointments

Associate Professor Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine

Member:

Bio-X

Cardiovascular Institute

Child Health Research Institute

Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine

Stanford Cancer Institute

Stanford Neurosciences Institute

Administrative appointments

Faculty Senate, Department of Pathology (2017 - Present)

Assistant Professor, Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine (2008 - 2014)

Honors & Awards

HHMI Faculty Scholar Award, Howard Hughes Medical Institute (2016)

New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Stem Cell Prize, New York Stem Cell Foundation (2014)

The Outstanding Young Investigator Award, International Society for Stem Cell Research (2013)

Ascina Award, Republic of Austria (2010)

Cozzarelli Prize for Outstanding Scientific Excellence, National Academy of Sciences USA (2009)

New Scholar in Aging, Ellison Medical Foundation (2010)

Robertson Investigator Award, New York Stem Cell Foundation (2010)

Donald E. and Delia B. Baxter Faculty Scholarship, Stanford University (2009)

Margaret and Herman Sokol Award, Biomedical Research (2007)

Longterm fellowship Human Frontiers Science Program Organisation, HFSP (2004-2006)

Boards, Advisory Committees

Professional Organizations Member, Society for Neuroscience (2003 - Present)

Member, International Society for Stem Cell Research (2004 - Present)

Editorial Board Member, Cell Stem Cell (2012 - Present)

Editorial Board Member, Stem Cell Reports (2013 - Present)

Member, Program Committee, Society for Neuroscience (2016 - Present)

Chair, Program Committee, International Society for Stem Cell Research (2017 - Present)

Professional Education

M.D., Technical University of Munich, Medicine (2000)

Team

I joined the Wernig lab as an LSRP in the summer of 2022 after graduating from UCLA. I’m interested in the regenerative capabilities of the human body and the molecular mechanisms underlying these regenerative systems, as well as the ways in which we can utilize these mechanisms to treat disease via tools such as cell and gene therapy. My research interests further include immunological topics such as cancer biology and the coevolution of pathogenic species and the immune response. In the Wernig lab, I am investigating methods of replacing dysfunctional microglia in the CNS in the context of neurodegenerative diseases, as well as the translational potential of gene editing and the role that genetically manipulated cells can play in treating such diseases. Outside the lab, I enjoy spending time at the beach, watching sports, and going on road trips with my friends.

Danwei Wu is a Stanford neurology resident in the Neuroscience Scholar Track and aspiring neuroimmunologist. Prior to starting residency, she completed an HHMI Medical Research Fellowship with Dr. Vann Bennett at Duke University studying neuron-specific membrane domains and their interaction with cytoskeletal structures. Her current research interest includes cell-based therapies for multiple sclerosis, molecular pathways of neuro-repair, and pathogenesis of autoimmunity. She is interested in developing new therapies for neurologic diseases. Outside of the lab, she enjoys hiking and reading science fiction.

I am a PhD student in the Neurosciences Interdepartmental Program and joined the lab in summer 2022. I am interested in developing methods to reprogram stem cells directly into oligodendrocytes. I then hope to use these cells to study the role of oligodendrocytes in aging and neurodegeneration. In my free time I like to read, ski, and play tennis.

I am a passionate cellular and molecular biologistwith expertise in research related to cancer, genomic/chromosomal instability, DNA damage response, epigenetics, proteomics and cellular identity. The latter topic attracted me to the Wernig lab where I aim to decipher the mechanisms that allow us to specifically switch the identity of a cell, converting differentiated somatic cells into induced neurons. I also work on a project that aims to integrate CRISPR/CAS9-mediated gene correction with iPS cell generation in order to establish a therapy for the devastating skin disease epidermolysis bullosa. In my free time I play underwater rugby, surf, spearfish and ski!

I am an undergraduate studying neurobiology and computer science. In the Wernig Lab, I am studying how the interactions between reprogramming factors and chromatin modifiers allow for fully developed fibrojacklynl@stanford.edublasts to reprogram into induced neuronal cells (iN).

I studied small GTPase signaling and how its perturbation can contribute to cancer and neurological disorders during my PhD training at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Since then, I have become increasingly fascinated by the epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation, and how changes in epigenome influence cell function and fate decisions. In the Wernig lab, I am currently investigating the interactions between the reprogramming factors and chromatin modifiers. More specifically, I am interested in finding out how such interactions enable a terminally differentiated cell—for example, a fibroblast—to acquire new transcriptional program that allows its reprogramming into induced neuron (iN).

I am a Bachelor of Science candidate in Bioengineering at Stanford University. My research in the Wernig Lag involves investigating the relationship between microglia and the IKBKAP gene, specifically its role in mechanisms such as microglia regeneration and the transdifferentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells into microglia-like cells.

Kayla is a PhD student in the Neurosciences Interdepartmental Program and joined the lab in summer 2022. She is interested in leveraging the lab's cell reprogramming techniques to study the roles of individual cell types in proteinopathies. She aims to faithfully recapitulate disease states and uncover the underlying molecular mechanisms that lead to neurodegeneration. In her free time, Kayla can be found birding, hiking, or performing with the Stanford Symphony Orchestra.

I received my BA in molecular and cell biology (Neurobiology focus) and computer science from UC Berkeley. I went on to do my PhD at Duke University, where I worked on engineering electrical synapses for precise neuromodulation in Kafui Dzirasa’s lab. Now, as a postdoc in Marius Wernig lab, I am interested in delving deeper into cellular engineering to better understand neuronal induction, synapse formation, and deliver treatment across the blood brain barrier using engineered microglia. In my free time, I enjoy cooking and coding/electrical engineering projects.

As a neurosurgical resident, my research interests include translational topics such as cell therapy and neuroregenerative mechanisms. In the Wernig lab, I study the cellular reprogramming potential of microglia. Moreover, I’m interested in the functional integration of induced neurons into neural systems.

I am an undergraduate student studying Human Biology. At Wernig Lab, I am helping to research how microglial cells organize and communicate with each other. I am interested in understanding the relationship between changes in the organization of microglia and other neural cells and the progression of neuronal diseases.

I received my Ph.D. in Neuroscience and Brain Technologies in 2021 from the University of Genoa and the Italian Institute of Technology, Italy. I joined the Wernig lab in December 2022. Here, I am interested in understanding how the microglia-derived factors end up in the neuronal lysosomes. Furthermore, I am interested in understanding how the accumulation and breakdown of these factors lead to neurodegenerative disorders using human induced pluripotent stem cell culture. I read non-fiction novels, sketch, and go for hikes in my free time.