Wernig Laboratory

October 9, 2024: Welcome new postdoc Kirill to the lab!

Sep 17, 2024: Jinzhao's paper accepted in principle!

Jul 11, 2024: Gernot's paper published in Nature Communications!

March 21, 2024: Marius Mader's paper comes out in Nature Neuroscience!

Oct 10, 2023: Yongjin receives the Sammy Kuo Award from the Neuroscience Institute - CONGRATULATIONS!

Yongjin's paper on cell therapy in a mouse AD model is published in Cell Stem Cells

Our lab is generally interested in the molecular mechanisms that determine cell fates

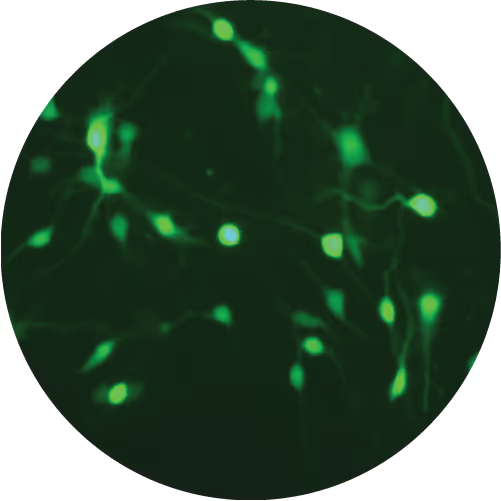

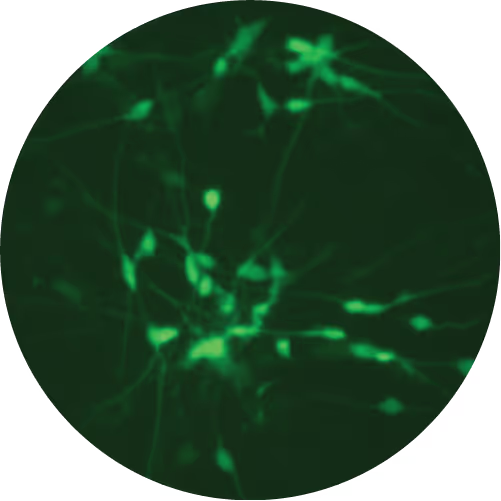

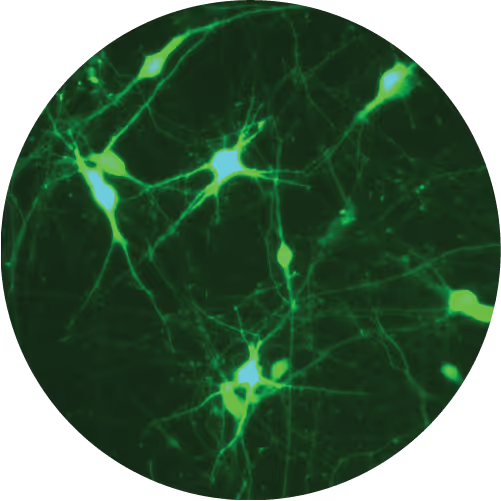

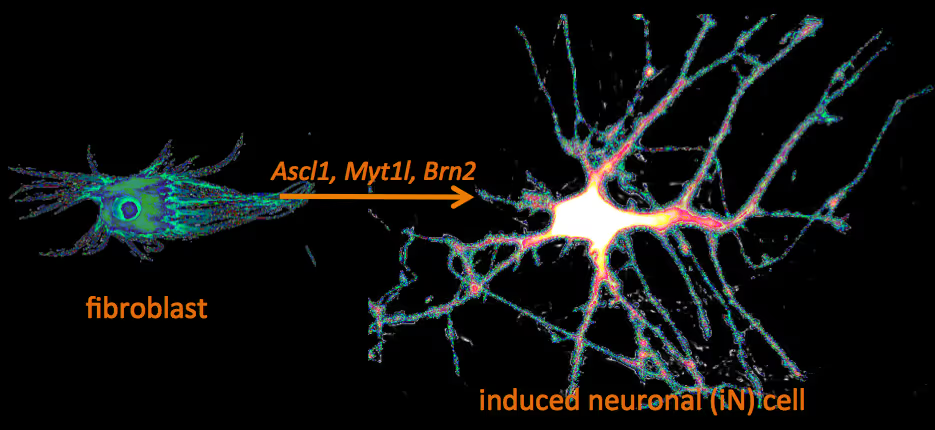

Recently, we have identified a pool of transcription factors that are sufficient to convert skin fibroblasts directly into functional neuronal cells that we termed induced neuronal (iN) cells. This was a surprising finding and indicated that direct lineage reprogramming may be applicable to many somatic cell types and many different directions. Indeed, following our work others have identified transcription factors that could induce cardiomyocytes, blood progenitors, and hepatocytes from fibroblasts.

We are now focussing on two major aspects of iN and iPS cell reprogramming:

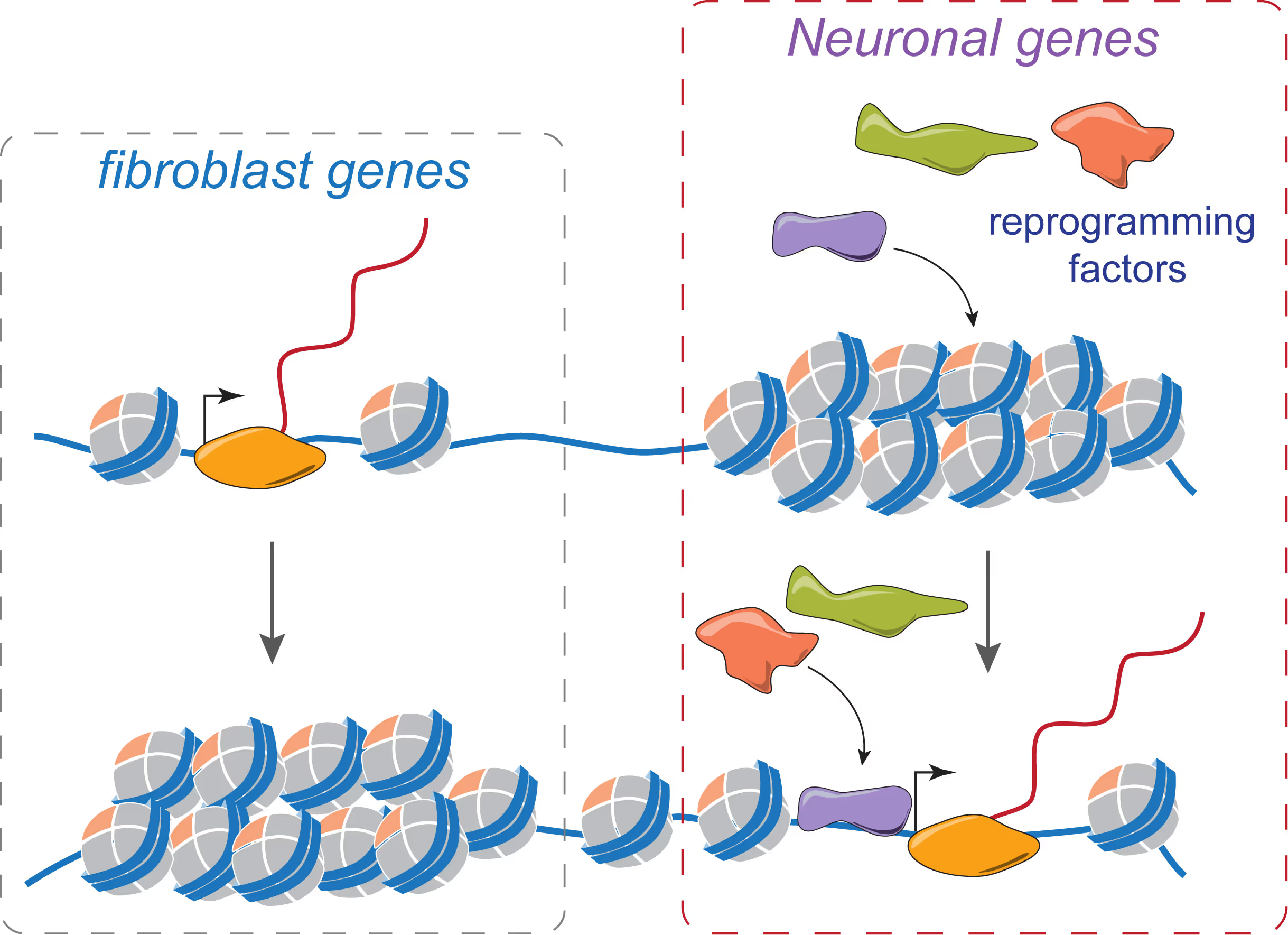

(i) we are fascinated by the puzzle how a hand full of transcription factors can so efficiently reprogram the entire epigenome of a cell so that it changes identity. To that end we are applying genome-wide expression analysis, chromatin immunoprecipitation, protein biochemistry, proteomics and functional screens.

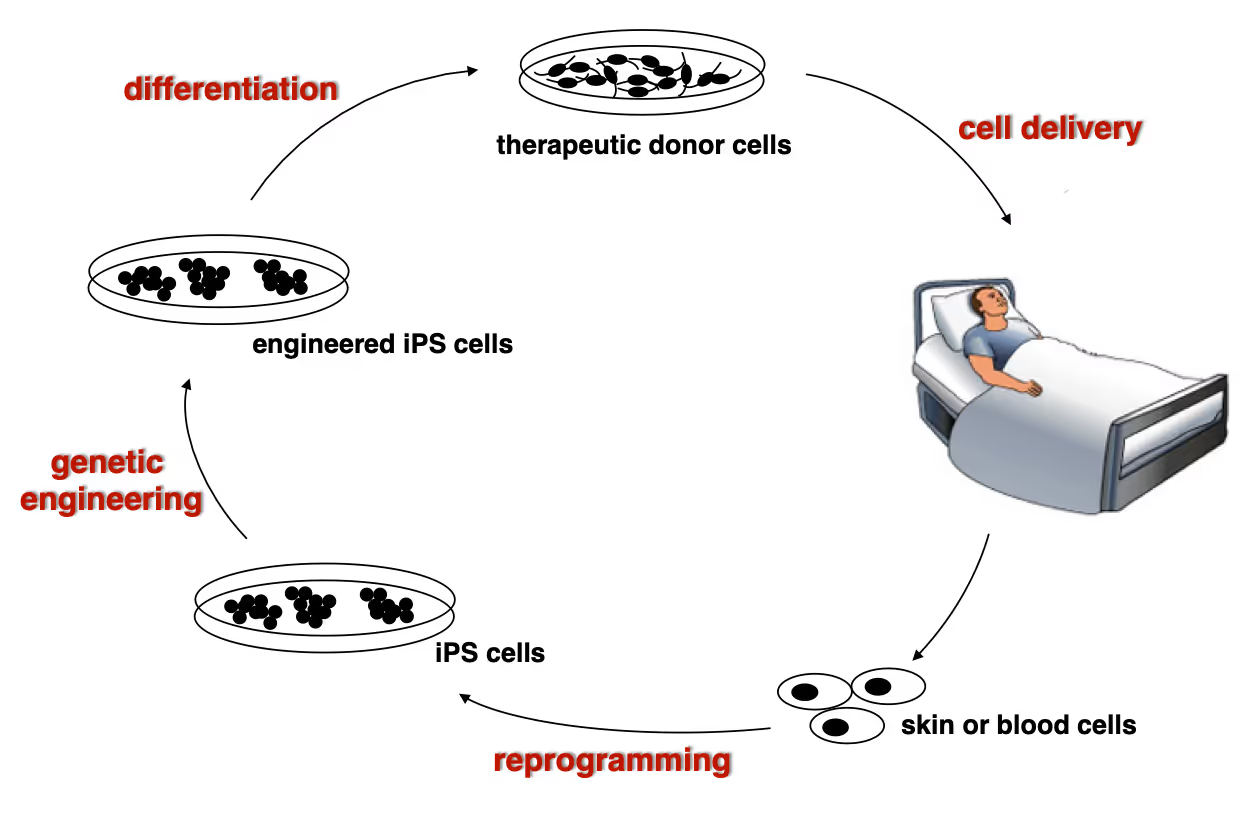

(ii) it is equally exciting to now use reprogramming methods as tools to study or treat certain diseases. iPS cells have the great advantage that they can easily be genetically manipulated rendering them ideal for treating monogenetic disorders when combined with cell transplantation-based therapies. In particular we are working on Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa in collaboration with Stanford's Dermatology Department. An exciting application of iN cell technology will be to try modeling neurological diseases in vitro. We perform both mouse and human experiments hoping to identify quantifiable phenotypes correlated with genotype and in a second step evaluate whether this assay could be used to discover novel drugs improve the disease progression.

Wernig Lab Research

Overview

Our lab is interested in the molecular mechanisms that define neural lineage identity focusing on transcription factors and chromatin biology. We use cellular reprogramming to understand how neurons are induced, how they mature and maintain their identity. Reprogramming also allows us to generate a novel tool box to study human neuronal and glial cell biology which become powerful human disease models in combination with genetic engineering. We further seek to develop reprogramming & genetic engineering approaches towards stem cell-based therapies. Finally, we study microglia-neuron interactions with the ultimate goal to understand the brain's immune system in health and disease and to exploit microglia for therapeutic and regenerative purposes.

Human neuronal cell disease modeling

Neurosychiatric diseases like autism and schizophrenia are highly complex brain disorders difficult to model in mice in part due to complex genetic etiology and sometimes affecting human-specific genes. We develop novel human cell models to investigate disease-relevant cell biological phenomena.

Generation of defined human neuronal cell types to study neuronal cell biology

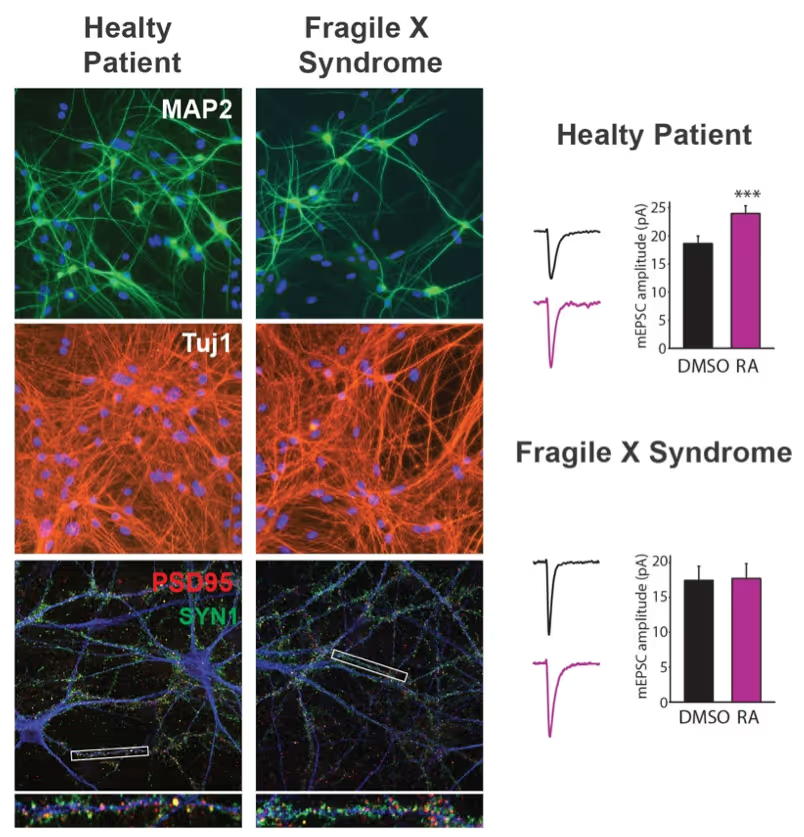

We have and continue to develop protocols to generate specific types of neurons such as pure glutamatergic and pure GABAergic neurons from human pluripotent stem cells using transcription factors. In combination with genetic engineering or deriving iPS cells from patients, we then interrogate the cell biology of human neurons that carry disease-causing mutations. A particular focus is on synaptic function as shown in the figure on the right on Fragile X Syndrome neurons in collaboration with Lu Chen and Tom Südhof's laboratories.

Making neurons from blood

The ability to generate functional induced neuronal cells from distantly related somatic cell types is fascinating but also offers the opportunity to obtain neurons from a larger cohort of human subjects. In particular blood is readily available and we showed can be efficiently converted into functional neurons from young and aged donors.

Developing next generation cell therapies

The combination of reprogramming and gene editing is truly powerful as it provides exciting new possibilities to generate cells that can be transplanted and have disease modifying activity. We currently apply this approach to restore mono-genetic diseases, but our vision goes beyond simple regenerative medicine. We will be able to genetically engineer designer cells that functionally integrate into diseased tissue equipped with sensing and intelligent disease-response mechanisms.

Towards a Phase 1 clinical trial for the fatal skin disease Epidermolysis Bullosa

Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa is a severe, blistering monogenetic skin disease caused by mutations in the gene coding for type VII collagen. We have developed a 1-step gene editing/iPS cell reprogramming method to rapidly generate patient iPS cells corrected for their disease-causing mutations in the Collagen7a1 gene. In collaboration with dermatologist Tony Oro we are developing a cell manufacturing process compatible with Good Manufacturing Procedures (GMP) to obtain FDA-approval for a first in man Phase I clinical trial with with a genetically engineered iPS cell product.

Exploiting glia cell transplantation to treat neurodegenerative disease

Both oligodendrocyte precursor cells as well as microglia can efficiently repopulate the brain. We are interested in exploiting the properties of these cells to develop novel cell therapies for the brain either to use the transplanted cells to restore function such as myelination, to alter the function of transplanted cells for therepeutic benefit, to use the cells as vehicles for therapeutic molecules, or ultimately to develop designer cells that are engineered with genetic synthetic biology circuits to sense and interfere with disease processes of the brain.

Mechanisms of neural cell lineage identity

We are interested in the molecular mechanisms that define neuronal and glial cell identity. We found sets of transcription factors that can convert fibroblasts or lymphocytes into neurons and oligodendrocytes. These factors are also operational during normal development and are largely responsible to induce terminal lineages from progenitor cells.

"On target" pioneer factors and chromatin remodeling during neuronal induction

We found that Ascl1, one of our reprogramming factors, has a unique ability to access its physiological targets even in fibroblasts where these sites are in a closed chromatin configuration. We are fascinated by this "on target" pioneering property and are investigating how Ascl1 can access its target sites in an unfavorable chromatin environment and how it then remodels the chromatin at these sites to activate the neuronal transcriptional program.

Maintenance of neuronal identity

Once neurons are made, there ought to be also mechanisms that maintain neuronal identity. We stumbled upon a novel repressive mechanism: The neuronal-specific transcription factor Myt1l continuosly represses many non-neuronal programs in neurons leaving the neuronal program open to activate by other factors and thereby ensuring stable neuronal gene expression. Myt1l was also recently found to be mutated in autism and schizophrenia.

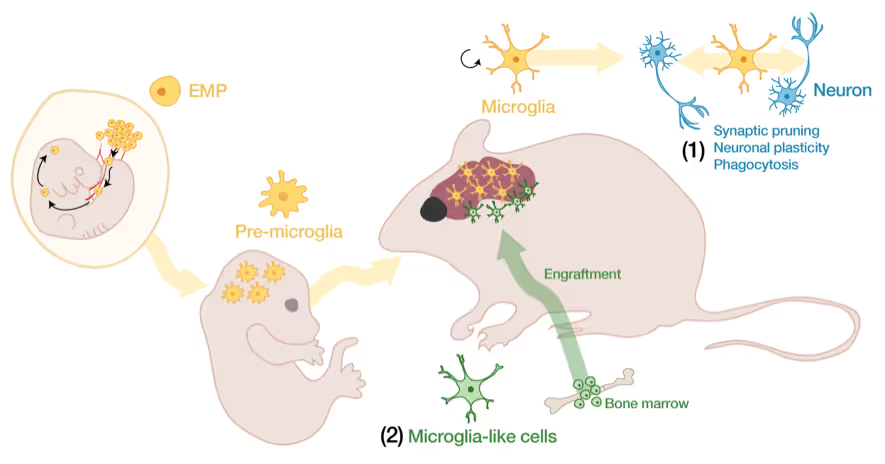

Microglia-neuron interactions in the healthy and diseased brain

Microglia, the brain's resident immune cells, are fascinating cells. They are derived from yolk sac progenitor cells early during development, are long-lived, and are not exchanged from bone marrow progenitor cells under physiological conditions. Microglia have been implicated in synaptic pruning, adult neurogenesis, and various brain diseases including Alzheimer's disease and Schizophrenia.

Developing an efficient microglia replacement system

We have developed a method to efficiently replace endogenous microglia from circulating cells without genetic manipulation. This does not happen physiologically but under certain conditions peripheral blood cells cross the blood-brain-barrier, migrate into the brain parenchyma and replace endogenous cells. We are investigating the cellular and molecular signals that enable circulating cells to invade the brain in order to further improve microglia replacement strategies.

The role of microglia in the normal and the diseased brain

Our ability to replace microglia provides us with a powerful tool to functionally perturb microglia function in normal and disease states. E.g. the microglial gene TREM2 is a strong Alzheimer's disease risk gene, but major questions about the neuro-immune interplay in the context of neurodegeneration and aging remain unsolved. Microglia replacement also provides an exciting prospect to develop novel cell therapies for a variety of brain diseases including enzyme deficiency syndromes, neurodegeneration, and brain tumors.

Lab Gene Expression Data

Publications

Pak C, Danko T, Mirabella VR, Wang J, Liu Y, Vangipuram M, Grieder S, Zhang X, Ward T, Huang YA, Jin K, Dexheimer P, Bardes E, Mitelpunkt A, Ma J, McLachlan M, Moore JC, Qu P, Purmann C, Dage JL, Swanson BJ, Urban AE, Aronow BJ, Pang ZP, Levinson DF, Wernig M, Südhof TC.

Heterozygous NRXN1 deletions constitute the most prevalent currently known single-gene mutation associated with schizophrenia, and additionally predispose to multiple other neurodevelopmental disorders. Engineered heterozygous NRXN1 deletions impaired neurotransmitter release in human neurons, suggesting a synaptic pathophysiological mechanism. Utilizing this observation for drug discovery, however, requires confidence in its robustness and validity. Here, we describe a multicenter effort to test the generality of this pivotal observation, using independent analyses at two laboratories of patient-derived and newly engineered human neurons with heterozygous NRXN1 deletions. Using neurons transdifferentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells that were derived from schizophrenia patients carrying heterozygous NRXN1 deletions, we observed the same synaptic impairment as in engineered NRXN1-deficient neurons. This impairment manifested as a large decrease in spontaneous synaptic events, in evoked synaptic responses, and in synaptic paired-pulse depression. Nrxn1-deficient mouse neurons generated from embryonic stem cells by the same method as human neurons did not exhibit impaired neurotransmitter release, suggesting a human-specific phenotype. Human NRXN1 deletions produced a reproducible increase in the levels of CASK, an intracellular NRXN1-binding protein, and were associated with characteristic gene-expression changes. Thus, heterozygous NRXN1 deletions robustly impair synaptic function in human neurons regardless of genetic background, enabling future drug discovery efforts.

Heterozygous NRXN1 deletions constitute the most prevalent currently known single-gene mutation associated with schizophrenia, and additionally predispose to multiple other neurodevelopmental disorders. Engineered heterozygous NRXN1 deletions impaired neurotransmitter release in human neurons, suggesting a synaptic pathophysiological mechanism. Utilizing this observation for drug discovery, however, requires confidence in its robustness and validity. Here, we describe a multicenter effort to test the generality of this pivotal observation, using independent analyses at two laboratories of patient-derived and newly engineered human neurons with heterozygous NRXN1 deletions. Using neurons transdifferentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells that were derived from schizophrenia patients carrying heterozygous NRXN1 deletions, we observed the same synaptic impairment as in engineered NRXN1-deficient neurons. This impairment manifested as a large decrease in spontaneous synaptic events, in evoked synaptic responses, and in synaptic paired-pulse depression. Nrxn1-deficient mouse neurons generated from embryonic stem cells by the same method as human neurons did not exhibit impaired neurotransmitter release, suggesting a human-specific phenotype. Human NRXN1 deletions produced a reproducible increase in the levels of CASK, an intracellular NRXN1-binding protein, and were associated with characteristic gene-expression changes. Thus, heterozygous NRXN1 deletions robustly impair synaptic function in human neurons regardless of genetic background, enabling future drug discovery efforts.

Raj N, McEachin ZT, Harousseau W, Zhou Y, Zhang F, Merritt-Garza ME, Taliaferro JM, Kalinowska M, Marro SG, Hales CM, Berry-Kravis E, Wolf-Ochoa MW, Martinez-Cerdeño V, Wernig M, Chen L, Klann E, Warren ST, Jin P, Wen Z, Bassell GJ.

Transcriptional silencing of the FMR1 gene in fragile X syndrome (FXS) leads to the loss of the RNA-binding protein FMRP. In addition to regulating mRNA translation and protein synthesis, emerging evidence suggests that FMRP acts to coordinate proliferation and differentiation during early neural development. However, whether loss of FMRP-mediated translational control is related to impaired cell fate specification in the developing human brain remains unknown. Here, we use human patient induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neural progenitor cells and organoids to model neurogenesis in FXS. We developed a high-throughput, in vitro assay that allows for the simultaneous quantification of protein synthesis and proliferation within defined neural subpopulations. We demonstrate that abnormal protein synthesis in FXS is coupled to altered cellular decisions to favor proliferative over neurogenic cell fates during early development. Furthermore, pharmacologic inhibition of elevated phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling corrects both excess protein synthesis and cell proliferation in a subset of patient neural cells.

Transcriptional silencing of the FMR1 gene in fragile X syndrome (FXS) leads to the loss of the RNA-binding protein FMRP. In addition to regulating mRNA translation and protein synthesis, emerging evidence suggests that FMRP acts to coordinate proliferation and differentiation during early neural development. However, whether loss of FMRP-mediated translational control is related to impaired cell fate specification in the developing human brain remains unknown. Here, we use human patient induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neural progenitor cells and organoids to model neurogenesis in FXS. We developed a high-throughput, in vitro assay that allows for the simultaneous quantification of protein synthesis and proliferation within defined neural subpopulations. We demonstrate that abnormal protein synthesis in FXS is coupled to altered cellular decisions to favor proliferative over neurogenic cell fates during early development. Furthermore, pharmacologic inhibition of elevated phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling corrects both excess protein synthesis and cell proliferation in a subset of patient neural cells.

Haag D, Mack N, Benites Goncalves da Silva P, Statz B, Clark J, Tanabe K, Sharma T, Jäger N, Jones DTW, Kawauchi D, Wernig M, Pfister SM

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is an aggressive childhood tumor of the brainstem with currently no curative treatment available. The vast majority of DIPGs carry a histone H3 mutation leading to a lysine 27-to-methionine exchange (H3K27M). We engineered human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to carry an inducible H3.3-K27M allele in the endogenous locus and studied the effects of the mutation in different disease-relevant neural cell types. H3.3-K27M upregulated bivalent promoter-associated developmental genes, producing diverse outcomes in different cell types. While being fatal for iPSCs, H3.3-K27M increased proliferation in neural stem cells (NSCs) and to a lesser extent in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs). Only NSCs gave rise to tumors upon induction of H3.3-K27M and TP53 inactivation in an orthotopic xenograft model recapitulating human DIPGs. In NSCs, H3.3-K27M leads to maintained expression of stemness and proliferative genes and a premature activation of OPC programs that together may cause tumor initiation.

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is an aggressive childhood tumor of the brainstem with currently no curative treatment available. The vast majority of DIPGs carry a histone H3 mutation leading to a lysine 27-to-methionine exchange (H3K27M). We engineered human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to carry an inducible H3.3-K27M allele in the endogenous locus and studied the effects of the mutation in different disease-relevant neural cell types. H3.3-K27M upregulated bivalent promoter-associated developmental genes, producing diverse outcomes in different cell types. While being fatal for iPSCs, H3.3-K27M increased proliferation in neural stem cells (NSCs) and to a lesser extent in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs). Only NSCs gave rise to tumors upon induction of H3.3-K27M and TP53 inactivation in an orthotopic xenograft model recapitulating human DIPGs. In NSCs, H3.3-K27M leads to maintained expression of stemness and proliferative genes and a premature activation of OPC programs that together may cause tumor initiation.

Saavedra L, Wallace K, Freudenrich T, Mall M, Mundy W, Davila J, Shafer T, Wernig M, Haag D

Assessment of neuroactive effects of chemicals in cell-based assays remains challenging as complex functional tissue is required for biologically relevant readouts. Recent in vitro models using rodent primary neural cultures grown on multielectrode arrays (MEAs) allow quantitative measurements of neural network activity suitable for neurotoxicity screening. However, robust systems for testing effects on network function in human neural models are still lacking. The increasing number of differentiation protocols for generating neurons from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) holds great potential to overcome the unavailability of human primary tissue and expedite cell-based assays. Yet, the variability in neuronal activity, prolonged ontogeny and rather immature stage of most neuronal cells derived by standard differentiation techniques greatly limit their utility for screening neurotoxic effects on human neural networks. Here, we used excitatory and inhibitory neurons, separately generated by direct reprogramming from hiPSCs, together with primary human astrocytes to establish highly functional cultures with defined cell ratios. Such neuron/glia co-cultures exhibited pronounced neuronal activity and robust formation of synchronized network activity on MEAs, albeit with noticeable delay compared to primary rat cortical cultures. We further investigated acute changes of network activity in human neuron/glia co-cultures and rat primary cortical cultures in response to compounds with known adverse neuroactive effects, including GABAA receptor antagonists and multiple pesticides. Importantly, we observed largely corresponding concentration-dependent effects on multiple neural network activity metrics using both neural culture types. These results demonstrate the utility of directly converted neuronal cells from hiPSCs for functional neurotoxicity screening of environmental chemicals.

Assessment of neuroactive effects of chemicals in cell-based assays remains challenging as complex functional tissue is required for biologically relevant readouts. Recent in vitro models using rodent primary neural cultures grown on multielectrode arrays (MEAs) allow quantitative measurements of neural network activity suitable for neurotoxicity screening. However, robust systems for testing effects on network function in human neural models are still lacking. The increasing number of differentiation protocols for generating neurons from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) holds great potential to overcome the unavailability of human primary tissue and expedite cell-based assays. Yet, the variability in neuronal activity, prolonged ontogeny and rather immature stage of most neuronal cells derived by standard differentiation techniques greatly limit their utility for screening neurotoxic effects on human neural networks. Here, we used excitatory and inhibitory neurons, separately generated by direct reprogramming from hiPSCs, together with primary human astrocytes to establish highly functional cultures with defined cell ratios. Such neuron/glia co-cultures exhibited pronounced neuronal activity and robust formation of synchronized network activity on MEAs, albeit with noticeable delay compared to primary rat cortical cultures. We further investigated acute changes of network activity in human neuron/glia co-cultures and rat primary cortical cultures in response to compounds with known adverse neuroactive effects, including GABAA receptor antagonists and multiple pesticides. Importantly, we observed largely corresponding concentration-dependent effects on multiple neural network activity metrics using both neural culture types. These results demonstrate the utility of directly converted neuronal cells from hiPSCs for functional neurotoxicity screening of environmental chemicals.

Michowski W, Chick JM, Chu C, Kolodziejczyk A, Wang Y, Suski JM, Abraham B, Anders L, Day D, Dunkl LM, Li Cheong Man M, Zhang T, Laphanuwat P, Bacon NA, Liu L, Fassl A, Sharma S, Otto T, Jecrois E, Han R, Sweeney KE, Marro S, Wernig M, Geng Y, Moses A, Li C, Gygi SP, Young RA, Sicinski P

The cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) drives cell division. To uncover additional functions of Cdk1, we generated knockin mice expressing an analog-sensitive version of Cdk1 in place of wild-type Cdk1. In our study, we focused on embryonic stem cells (ESCs), because this cell type displays particularly high Cdk1 activity. We found that in ESCs, a large fraction of Cdk1 substrates is localized on chromatin. Cdk1 phosphorylates many proteins involved in epigenetic regulation, including writers and erasers of all major histone marks. Consistent with these findings, inhibition of Cdk1 altered histone-modification status of ESCs. High levels of Cdk1 in ESCs phosphorylate and partially inactivate Dot1l, the H3K79 methyltransferase responsible for placing activating marks on gene bodies. Decrease of Cdk1 activity during ESC differentiation de-represses Dot1l, thereby allowing coordinated expression of differentiation genes. These analyses indicate that Cdk1 functions to maintain the epigenetic identity of ESCs.

The cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) drives cell division. To uncover additional functions of Cdk1, we generated knockin mice expressing an analog-sensitive version of Cdk1 in place of wild-type Cdk1. In our study, we focused on embryonic stem cells (ESCs), because this cell type displays particularly high Cdk1 activity. We found that in ESCs, a large fraction of Cdk1 substrates is localized on chromatin. Cdk1 phosphorylates many proteins involved in epigenetic regulation, including writers and erasers of all major histone marks. Consistent with these findings, inhibition of Cdk1 altered histone-modification status of ESCs. High levels of Cdk1 in ESCs phosphorylate and partially inactivate Dot1l, the H3K79 methyltransferase responsible for placing activating marks on gene bodies. Decrease of Cdk1 activity during ESC differentiation de-represses Dot1l, thereby allowing coordinated expression of differentiation genes. These analyses indicate that Cdk1 functions to maintain the epigenetic identity of ESCs.

Lee QY, Mall M, Chanda S, Zhou B, Sharma KS, Schaukowitch K, Adrian-Segarra JM, Grieder SD, Kareta MS, Wapinski OL, Ang CE, Li R, Südhof TC, Chang HY, Wernig M

The on-target pioneer factors Ascl1 and Myod1 are sequence-related but induce two developmentally unrelated lineages-that is, neuronal and muscle identities, respectively. It is unclear how these two basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) factors mediate such fundamentally different outcomes. The chromatin binding of Ascl1 and Myod1 was surprisingly similar in fibroblasts, yet their transcriptional outputs were drastically different. We found that quantitative binding differences explained differential chromatin remodelling and gene activation. Although strong Ascl1 binding was exclusively associated with bHLH motifs, strong Myod1-binding sites were co-enriched with non-bHLH motifs, possibly explaining why Ascl1 is less context dependent. Finally, we observed that promiscuous binding of Myod1 to neuronal targets results in neuronal reprogramming when the muscle program is inhibited by Myt1l. Our findings suggest that chromatin access of on-target pioneer factors is primarily driven by the protein-DNA interaction, unlike ordinary context-dependent transcription factors, and that promiscuous transcription factor binding requires specific silencing mechanisms to ensure lineage fidelity.

The on-target pioneer factors Ascl1 and Myod1 are sequence-related but induce two developmentally unrelated lineages-that is, neuronal and muscle identities, respectively. It is unclear how these two basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) factors mediate such fundamentally different outcomes. The chromatin binding of Ascl1 and Myod1 was surprisingly similar in fibroblasts, yet their transcriptional outputs were drastically different. We found that quantitative binding differences explained differential chromatin remodelling and gene activation. Although strong Ascl1 binding was exclusively associated with bHLH motifs, strong Myod1-binding sites were co-enriched with non-bHLH motifs, possibly explaining why Ascl1 is less context dependent. Finally, we observed that promiscuous binding of Myod1 to neuronal targets results in neuronal reprogramming when the muscle program is inhibited by Myt1l. Our findings suggest that chromatin access of on-target pioneer factors is primarily driven by the protein-DNA interaction, unlike ordinary context-dependent transcription factors, and that promiscuous transcription factor binding requires specific silencing mechanisms to ensure lineage fidelity.

Li L, Wang Y, Torkelson JL, Shankar G, Pattison JM, Zhen HH, Fang F, Duren Z, Xin J, Gaddam S, Melo SP, Piekos SN, Li J, Liaw EJ, Chen L, Li R, Wernig M, Wong WH, Chang HY, Oro AE

Tissue development results from lineage-specific transcription factors (TFs) programming a dynamic chromatin landscape through progressive cell fate transitions. Here, we define epigenomic landscape during epidermal differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) and create inference networks that integrate gene expression, chromatin accessibility, and TF binding to define regulatory mechanisms during keratinocyte specification. We found two critical chromatin networks during surface ectoderm initiation and keratinocyte maturation, which are driven by TFAP2C and p63, respectively. Consistently, TFAP2C, but not p63, is sufficient to initiate surface ectoderm differentiation, and TFAP2C-initiated progenitor cells are capable of maturing into functional keratinocytes. Mechanistically, TFAP2C primes the surface ectoderm chromatin landscape and induces p63 expression and binding sites, thus allowing maturation factor p63 to positively autoregulate its own expression and close a subset of the TFAP2C-initiated surface ectoderm program. Our work provides a general framework to infer TF networks controlling chromatin transitions that will facilitate future regenerative medicine advances.

Tissue development results from lineage-specific transcription factors (TFs) programming a dynamic chromatin landscape through progressive cell fate transitions. Here, we define epigenomic landscape during epidermal differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) and create inference networks that integrate gene expression, chromatin accessibility, and TF binding to define regulatory mechanisms during keratinocyte specification. We found two critical chromatin networks during surface ectoderm initiation and keratinocyte maturation, which are driven by TFAP2C and p63, respectively. Consistently, TFAP2C, but not p63, is sufficient to initiate surface ectoderm differentiation, and TFAP2C-initiated progenitor cells are capable of maturing into functional keratinocytes. Mechanistically, TFAP2C primes the surface ectoderm chromatin landscape and induces p63 expression and binding sites, thus allowing maturation factor p63 to positively autoregulate its own expression and close a subset of the TFAP2C-initiated surface ectoderm program. Our work provides a general framework to infer TF networks controlling chromatin transitions that will facilitate future regenerative medicine advances.

Ang CE, Ma Q, Wapinski OL, Fan S, Flynn RA, Lee QY, Coe B, Onoguchi M, Olmos VH, Do BT, Dukes-Rimsky L, Xu J, Tanabe K, Wang L, Elling U, Penninger JM, Zhao Y, Qu K, Eichler EE, Srivastava A, Wernig M, Chang HY.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been shown to act as important cell biological regulators including cell fate decisions but are often ignored in human genetics. Combining differential lncRNA expression during neuronal lineage induction with copy number variation morbidity maps of a cohort of children with autism spectrum disorder/intellectual disability versus healthy controls revealed focal genomic mutations affecting several lncRNA candidate loci. Here we find that a t(5:12) chromosomal translocation in a family manifesting neurodevelopmental symptoms disrupts specifically lnc-NR2F1. We further show that lnc-NR2F1 is an evolutionarily conserved lncRNA functionally enhances induced neuronal cell maturation and directly occupies and regulates transcription of neuronal genes including autism-associated genes. Thus, integrating human genetics and functional testing in neuronal lineage induction is a promising approach for discovering candidate lncRNAs involved in neurodevelopmental diseases.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been shown to act as important cell biological regulators including cell fate decisions but are often ignored in human genetics. Combining differential lncRNA expression during neuronal lineage induction with copy number variation morbidity maps of a cohort of children with autism spectrum disorder/intellectual disability versus healthy controls revealed focal genomic mutations affecting several lncRNA candidate loci. Here we find that a t(5:12) chromosomal translocation in a family manifesting neurodevelopmental symptoms disrupts specifically lnc-NR2F1. We further show that lnc-NR2F1 is an evolutionarily conserved lncRNA functionally enhances induced neuronal cell maturation and directly occupies and regulates transcription of neuronal genes including autism-associated genes. Thus, integrating human genetics and functional testing in neuronal lineage induction is a promising approach for discovering candidate lncRNAs involved in neurodevelopmental diseases.

Luo C, Lee QY, Wapinski O, Castanon R, Nery JR, Mall M, Kareta MS, Cullen SM, Goodell MA, Chang HY, Wernig M, Ecker JR.

Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts to neurons induces widespread cellular and transcriptional reconfiguration. Here, we characterized global epigenomic changes during the direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neurons using whole-genome base-resolution DNA methylation (mC) sequencing. We found that the pioneer transcription factor Ascl1 alone is sufficient for inducing the uniquely neuronal feature of non-CG methylation (mCH), but co-expression of Brn2 and Mytl1 was required to establish a global mCH pattern reminiscent of mature cortical neurons. Ascl1 alone induced promoter CG methylation (mCG) of fibroblast specific genes, while BAM overexpression additionally targets a competing myogenic program and directs a more faithful conversion to neuronal cells. Ascl1 induces local demethylation at its binding sites. Surprisingly, co-expression with Brn2 and Mytl1 inhibited the ability of Ascl1 to induce demethylation, suggesting a contextual regulation of transcription factor - epigenome interaction. Finally, we found that de novo methylation by DNMT3A is required for efficient neuronal reprogramming.

Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts to neurons induces widespread cellular and transcriptional reconfiguration. Here, we characterized global epigenomic changes during the direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neurons using whole-genome base-resolution DNA methylation (mC) sequencing. We found that the pioneer transcription factor Ascl1 alone is sufficient for inducing the uniquely neuronal feature of non-CG methylation (mCH), but co-expression of Brn2 and Mytl1 was required to establish a global mCH pattern reminiscent of mature cortical neurons. Ascl1 alone induced promoter CG methylation (mCG) of fibroblast specific genes, while BAM overexpression additionally targets a competing myogenic program and directs a more faithful conversion to neuronal cells. Ascl1 induces local demethylation at its binding sites. Surprisingly, co-expression with Brn2 and Mytl1 inhibited the ability of Ascl1 to induce demethylation, suggesting a contextual regulation of transcription factor - epigenome interaction. Finally, we found that de novo methylation by DNMT3A is required for efficient neuronal reprogramming.

Shariati SA, Dominguez A, Xie S, Wernig M, Qi LS, Skotheim JM.

The control of gene expression by transcription factor binding sites frequently determines phenotype. However, it is difficult to determine the function of single transcription factor binding sites within larger transcription networks. Here, we use deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) to disrupt binding to specific sites, a method we term CRISPRd. Since CRISPR guide RNAs are longer than transcription factor binding sites, flanking sequence can be used to target specific sites. Targeting dCas9 to an Oct4 site in the Nanog promoter displaced Oct4 from this site, reduced Nanog expression, and slowed division. In contrast, disrupting the Oct4 binding site adjacent to Pax6 upregulated Pax6 transcription and disrupting Nanog binding its own promoter upregulated its transcription. Thus, we can easily distinguish between activating and repressing binding sites and examine autoregulation. Finally, multiple guide RNA expression allows simultaneous inhibition of multiple binding sites, and conditionally destabilized dCas9 allows rapid reversibility.

The control of gene expression by transcription factor binding sites frequently determines phenotype. However, it is difficult to determine the function of single transcription factor binding sites within larger transcription networks. Here, we use deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) to disrupt binding to specific sites, a method we term CRISPRd. Since CRISPR guide RNAs are longer than transcription factor binding sites, flanking sequence can be used to target specific sites. Targeting dCas9 to an Oct4 site in the Nanog promoter displaced Oct4 from this site, reduced Nanog expression, and slowed division. In contrast, disrupting the Oct4 binding site adjacent to Pax6 upregulated Pax6 transcription and disrupting Nanog binding its own promoter upregulated its transcription. Thus, we can easily distinguish between activating and repressing binding sites and examine autoregulation. Finally, multiple guide RNA expression allows simultaneous inhibition of multiple binding sites, and conditionally destabilized dCas9 allows rapid reversibility.

Marro SG, Chanda S, Yang N, Janas JA, Valperga G, Trotter J, Zhou B, Merrill S, Yousif I, Shelby H, Vogel H, Kalani MYS, Südhof TC, Wernig M.

The autism-associated synaptic-adhesion gene Neuroligin-4 (NLGN4) is poorly conserved evolutionarily, limiting conclusions from Nlgn4 mouse models for human cells. Here, we show that the cellular and subcellular expression of human and murine Neuroligin-4 differ, with human Neuroligin-4 primarily expressed in cerebral cortex and localized to excitatory synapses. Overexpression of NLGN4 in human embryonic stem cell-derived neurons resulted in an increase in excitatory synapse numbers but a remarkable decrease in synaptic strength. Human neurons carrying the syndromic autism mutation NLGN4-R704C also formed more excitatory synapses but with increased functional synaptic transmission due to a postsynaptic mechanism, while genetic loss of NLGN4 did not significantly affect synapses in the human neurons analyzed. Thus, the NLGN4-R704C mutation represents a change-of-function mutation. Our work reveals contrasting roles of NLGN4 in human and mouse neurons, suggesting that human evolution has impacted even fundamental cell biological processes generally assumed to be highly conserved.

The autism-associated synaptic-adhesion gene Neuroligin-4 (NLGN4) is poorly conserved evolutionarily, limiting conclusions from Nlgn4 mouse models for human cells. Here, we show that the cellular and subcellular expression of human and murine Neuroligin-4 differ, with human Neuroligin-4 primarily expressed in cerebral cortex and localized to excitatory synapses. Overexpression of NLGN4 in human embryonic stem cell-derived neurons resulted in an increase in excitatory synapse numbers but a remarkable decrease in synaptic strength. Human neurons carrying the syndromic autism mutation NLGN4-R704C also formed more excitatory synapses but with increased functional synaptic transmission due to a postsynaptic mechanism, while genetic loss of NLGN4 did not significantly affect synapses in the human neurons analyzed. Thus, the NLGN4-R704C mutation represents a change-of-function mutation. Our work reveals contrasting roles of NLGN4 in human and mouse neurons, suggesting that human evolution has impacted even fundamental cell biological processes generally assumed to be highly conserved.

Nobuta H, Yang N, Ng YH, Marro SG, Sabeur K, Chavali M, Stockley JH, Killilea DW, Walter PB, Zhao C, Huie P Jr, Goldman SA, Kriegstein AR, Franklin RJM, Rowitch DH, Wernig M.

Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (PMD) is an X-linked leukodystrophy caused by mutations in Proteolipid Protein 1 (PLP1), encoding a major myelin protein, resulting in profound developmental delay and early lethality. Previous work showed involvement of unfolded protein response (UPR) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathways, but poor PLP1 genotype-phenotype associations suggest additional pathogenetic mechanisms. Using induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) and gene-correction, we show that patient-derived oligodendrocytes can develop to the pre-myelinating stage, but subsequently undergo cell death. Mutant oligodendrocytes demonstrated key hallmarks of ferroptosis including lipid peroxidation, abnormal iron metabolism, and hypersensitivity to free iron. Iron chelation rescued mutant oligodendrocyte apoptosis, survival, and differentiationin vitro, and post-transplantation in vivo. Finally, systemic treatment of Plp1 mutant Jimpy mice with deferiprone, a small molecule iron chelator, reduced oligodendrocyte apoptosis and enabled myelin formation. Thus, oligodendrocyte iron-induced cell death and myelination is rescued by iron chelation in PMD pre-clinical models.

Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (PMD) is an X-linked leukodystrophy caused by mutations in Proteolipid Protein 1 (PLP1), encoding a major myelin protein, resulting in profound developmental delay and early lethality. Previous work showed involvement of unfolded protein response (UPR) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathways, but poor PLP1 genotype-phenotype associations suggest additional pathogenetic mechanisms. Using induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) and gene-correction, we show that patient-derived oligodendrocytes can develop to the pre-myelinating stage, but subsequently undergo cell death. Mutant oligodendrocytes demonstrated key hallmarks of ferroptosis including lipid peroxidation, abnormal iron metabolism, and hypersensitivity to free iron. Iron chelation rescued mutant oligodendrocyte apoptosis, survival, and differentiationin vitro, and post-transplantation in vivo. Finally, systemic treatment of Plp1 mutant Jimpy mice with deferiprone, a small molecule iron chelator, reduced oligodendrocyte apoptosis and enabled myelin formation. Thus, oligodendrocyte iron-induced cell death and myelination is rescued by iron chelation in PMD pre-clinical models.

Essayan-Perez S, Zhou B, Nabet AM, Wernig M, Huang YA.

One in three people will develop Alzheimer's disease (AD) or another dementia and, despite intense research efforts, treatment options remain inadequate. Understanding the mechanisms of AD pathogenesis remains our principal hurdle to developing effective therapeutics to tackle this looming medical crisis. In light of recent discoveries from whole-genome sequencing and technical advances in humanized models, studying disease risk genes with induced human neural cells presents unprecedented advantages. Here, we first review the current knowledge of the proposed mechanisms underlying AD and focus on modern genetic insights to inform future studies. To highlight the utility of human pluripotent stem cell-based innovations, we then present an update on efforts in recapitulating the pathophysiology by induced neuronal, non-neuronal and a collection of brain cell types, departing from the neuron-centric convention. Lastly, we examine the translational potentials of such approaches, and provide our perspectives on the promise they offer to deepen our understanding of AD pathogenesis and to accelerate the development of intervention strategies for patients and risk carriers.

One in three people will develop Alzheimer's disease (AD) or another dementia and, despite intense research efforts, treatment options remain inadequate. Understanding the mechanisms of AD pathogenesis remains our principal hurdle to developing effective therapeutics to tackle this looming medical crisis. In light of recent discoveries from whole-genome sequencing and technical advances in humanized models, studying disease risk genes with induced human neural cells presents unprecedented advantages. Here, we first review the current knowledge of the proposed mechanisms underlying AD and focus on modern genetic insights to inform future studies. To highlight the utility of human pluripotent stem cell-based innovations, we then present an update on efforts in recapitulating the pathophysiology by induced neuronal, non-neuronal and a collection of brain cell types, departing from the neuron-centric convention. Lastly, we examine the translational potentials of such approaches, and provide our perspectives on the promise they offer to deepen our understanding of AD pathogenesis and to accelerate the development of intervention strategies for patients and risk carriers.

Ishii T, Ishikawa M, Fujimori K, Maeda T, Kushima I, Arioka Y, Mori D, Nakatake Y, Yamagata B, Nio S, Kato TA, Yang N, Wernig M, Kanba S, Mimura M, Ozaki N, Okano H.

Bipolar disorder (BP) and schizophrenia (SCZ) are major psychiatric disorders, but the molecular mechanisms underlying the complicated pathologies of these disorders remain unclear. It is difficult to establish adequate in vitro models for pathological analysis because of the heterogeneity of these disorders. In the present study, to recapitulate the pathologies of these disorders in vitro, we established in vitro models by differentiating mature neurons from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) derived from BP and SCZ patient with contributive copy number variations, as follows: two BP patients with PCDH15 deletion and one SCZ patient with RELN deletion. Glutamatergic neurons and GABAergic neurons were induced from hiPSCs under optimized conditions. Both types of induced neurons from both hiPSCs exhibited similar phenotypes of MAP2 (microtubule-associated protein 2)-positive dendrite shortening and decreasing synapse numbers. Additionally, we analyzed isogenic PCDH15- or RELN-deleted cells. The dendrite and synapse phenotypes of isogenic neurons were partially similar to those of patient-derived neurons. These results suggest that the observed phenotypes are general phenotypes of psychiatric disorders, and our in vitro models using hiPSC-based technology may be suitable for analysis of the pathologies of psychiatric disorders.

Bipolar disorder (BP) and schizophrenia (SCZ) are major psychiatric disorders, but the molecular mechanisms underlying the complicated pathologies of these disorders remain unclear. It is difficult to establish adequate in vitro models for pathological analysis because of the heterogeneity of these disorders. In the present study, to recapitulate the pathologies of these disorders in vitro, we established in vitro models by differentiating mature neurons from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) derived from BP and SCZ patient with contributive copy number variations, as follows: two BP patients with PCDH15 deletion and one SCZ patient with RELN deletion. Glutamatergic neurons and GABAergic neurons were induced from hiPSCs under optimized conditions. Both types of induced neurons from both hiPSCs exhibited similar phenotypes of MAP2 (microtubule-associated protein 2)-positive dendrite shortening and decreasing synapse numbers. Additionally, we analyzed isogenic PCDH15- or RELN-deleted cells. The dendrite and synapse phenotypes of isogenic neurons were partially similar to those of patient-derived neurons. These results suggest that the observed phenotypes are general phenotypes of psychiatric disorders, and our in vitro models using hiPSC-based technology may be suitable for analysis of the pathologies of psychiatric disorders.

Mahmoudi S, Mancini E, Xu L, Moore A, Jahanbani F, Hebestreit K, Srinivasan R, Li X, Devarajan K, Prélot L, Ang CE, Shibuya Y, Benayoun BA, Chang ALS, Wernig M, Wysocka J, Longaker MT, Snyder MP, Brunet A.

Age-associated chronic inflammation (inflammageing) is a central hallmark of ageing1, but its influence on specific cells remains largely unknown. Fibroblasts are present in most tissues and contribute to wound healing2,3. They are also the most widely used cell type for reprogramming to induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, a process that has implications for regenerative medicine and rejuvenation strategies4. Here we show that fibroblast cultures from old mice secrete inflammatory cytokines and exhibit increased variability in the efficiency of iPS cell reprogramming between mice. Variability between individuals is emerging as a feature of old age5-8, but the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. To identify drivers of this variability, we performed multi-omics profiling of fibroblast cultures from young and old mice that have different reprogramming efficiencies. This approach revealed that fibroblast cultures from old mice contain 'activated fibroblasts' that secrete inflammatory cytokines, and that the proportion of activated fibroblasts in a culture correlates with the reprogramming efficiency of that culture. Experiments in which conditioned medium was swapped between cultures showed that extrinsic factors secreted by activated fibroblasts underlie part of the variability between mice in reprogramming efficiency, and we have identified inflammatory cytokines, including TNF, as key contributors. Notably, old mice also exhibited variability in wound healing rate in vivo. Single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis identified distinct subpopulations of fibroblasts with different cytokine expression and signalling in the wounds of old mice with slow versus fast healing rates. Hence, a shift in fibroblast composition, and the ratio of inflammatory cytokines that they secrete, may drive the variability between mice in reprogramming in vitro and influence wound healing rate in vivo. This variability may reflect distinct stochastic ageing trajectories between individuals, and could help in developing personalized strategies to improve iPS cell generation and wound healing in elderly individuals.

Age-associated chronic inflammation (inflammageing) is a central hallmark of ageing1, but its influence on specific cells remains largely unknown. Fibroblasts are present in most tissues and contribute to wound healing2,3. They are also the most widely used cell type for reprogramming to induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, a process that has implications for regenerative medicine and rejuvenation strategies4. Here we show that fibroblast cultures from old mice secrete inflammatory cytokines and exhibit increased variability in the efficiency of iPS cell reprogramming between mice. Variability between individuals is emerging as a feature of old age5-8, but the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. To identify drivers of this variability, we performed multi-omics profiling of fibroblast cultures from young and old mice that have different reprogramming efficiencies. This approach revealed that fibroblast cultures from old mice contain 'activated fibroblasts' that secrete inflammatory cytokines, and that the proportion of activated fibroblasts in a culture correlates with the reprogramming efficiency of that culture. Experiments in which conditioned medium was swapped between cultures showed that extrinsic factors secreted by activated fibroblasts underlie part of the variability between mice in reprogramming efficiency, and we have identified inflammatory cytokines, including TNF, as key contributors. Notably, old mice also exhibited variability in wound healing rate in vivo. Single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis identified distinct subpopulations of fibroblasts with different cytokine expression and signalling in the wounds of old mice with slow versus fast healing rates. Hence, a shift in fibroblast composition, and the ratio of inflammatory cytokines that they secrete, may drive the variability between mice in reprogramming in vitro and influence wound healing rate in vivo. This variability may reflect distinct stochastic ageing trajectories between individuals, and could help in developing personalized strategies to improve iPS cell generation and wound healing in elderly individuals.

Huang YA, Zhou B, Nabet AM, Wernig M, Südhof TC.

In blood, apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is a component of circulating lipoproteins and mediates the clearance of these lipoproteins from blood by binding to ApoE receptors. Humans express three genetic ApoE variants, ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4, which exhibit distinct ApoE receptor-binding properties and differentially affect Alzheimer's disease (AD), such that ApoE2 protects against, and ApoE4 predisposes to AD. In brain, ApoE-containing lipoproteins are secreted by activated astrocytes and microglia, but their functions and role in AD pathogenesis are largely unknown. Ample evidence suggests that ApoE4 induces microglial dysregulation and impedes Aβ clearance in AD, but the direct neuronal effects of ApoE variants are poorly studied. Extending previous studies, we here demonstrate that the three ApoE variants differentially activate multiple neuronal signaling pathways and regulate synaptogenesis. Specifically, using human neurons (male embryonic stem cell-derived) cultured in the absence of glia to exclude indirect glial mechanisms, we show that ApoE broadly stimulates signal transduction cascades. Among others, such stimulation enhances APP synthesis and synapse formation with an ApoE4>ApoE3>ApoE2 potency rank order, paralleling the relative risk for AD conferred by these ApoE variants. Unlike the previously described induction of APP transcription, however, ApoE-induced synaptogenesis involves CREB activation rather than cFos activation. We thus propose that in brain, ApoE acts as a glia-secreted signal that activates neuronal signaling pathways. The parallel potency rank order of ApoE4>ApoE3>ApoE2 in AD risk and neuronal signaling suggests that ApoE4 may in an apparent paradox promote AD pathogenesis by causing a chronic increase in signaling, possibly via enhancing APP expression.SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Humans express three genetic variants of apolipoprotein E (ApoE), ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4. ApoE4 constitutes the most important genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (AD), whereas ApoE2 protects against AD. Significant evidence suggests that ApoE4 impairs microglial function and impedes astrocytic Aβ clearance in brain, but the direct neuronal effects of ApoE are poorly understood, and the differences between ApoE variants in these effects are unclear. Here, we report that ApoE acts on neurons as a glia-secreted signaling molecule that, among others, enhances synapse formation. In activating neuronal signaling, the three ApoE variants exhibit a differential potency of ApoE4>ApoE3>ApoE2, which mirrors their relative effects on AD risk, suggesting that differential signaling by ApoE variants may contribute to AD pathogenesis.

In blood, apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is a component of circulating lipoproteins and mediates the clearance of these lipoproteins from blood by binding to ApoE receptors. Humans express three genetic ApoE variants, ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4, which exhibit distinct ApoE receptor-binding properties and differentially affect Alzheimer's disease (AD), such that ApoE2 protects against, and ApoE4 predisposes to AD. In brain, ApoE-containing lipoproteins are secreted by activated astrocytes and microglia, but their functions and role in AD pathogenesis are largely unknown. Ample evidence suggests that ApoE4 induces microglial dysregulation and impedes Aβ clearance in AD, but the direct neuronal effects of ApoE variants are poorly studied. Extending previous studies, we here demonstrate that the three ApoE variants differentially activate multiple neuronal signaling pathways and regulate synaptogenesis. Specifically, using human neurons (male embryonic stem cell-derived) cultured in the absence of glia to exclude indirect glial mechanisms, we show that ApoE broadly stimulates signal transduction cascades. Among others, such stimulation enhances APP synthesis and synapse formation with an ApoE4>ApoE3>ApoE2 potency rank order, paralleling the relative risk for AD conferred by these ApoE variants. Unlike the previously described induction of APP transcription, however, ApoE-induced synaptogenesis involves CREB activation rather than cFos activation. We thus propose that in brain, ApoE acts as a glia-secreted signal that activates neuronal signaling pathways. The parallel potency rank order of ApoE4>ApoE3>ApoE2 in AD risk and neuronal signaling suggests that ApoE4 may in an apparent paradox promote AD pathogenesis by causing a chronic increase in signaling, possibly via enhancing APP expression.SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Humans express three genetic variants of apolipoprotein E (ApoE), ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4. ApoE4 constitutes the most important genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (AD), whereas ApoE2 protects against AD. Significant evidence suggests that ApoE4 impairs microglial function and impedes astrocytic Aβ clearance in brain, but the direct neuronal effects of ApoE are poorly understood, and the differences between ApoE variants in these effects are unclear. Here, we report that ApoE acts on neurons as a glia-secreted signaling molecule that, among others, enhances synapse formation. In activating neuronal signaling, the three ApoE variants exhibit a differential potency of ApoE4>ApoE3>ApoE2, which mirrors their relative effects on AD risk, suggesting that differential signaling by ApoE variants may contribute to AD pathogenesis.

Chanda S, Ang CE, Lee QY, Ghebrial M, Haag D, Shibuya Y, Wernig M, Südhof TC.

Human pluripotent stem cells can be rapidly converted into functional neurons by ectopic expression of proneural transcription factors. Here we show that directly reprogrammed neurons, despite their rapid maturation kinetics, can model teratogenic mechanisms that specifically affect early neurodevelopment. We delineated distinct phases of in vitro maturation during reprogramming of human neurons and assessed the cellular phenotypes of valproic acid (VPA), a teratogenic drug. VPA exposure caused chronic impairment of dendritic morphology and functional properties of developing neurons, but not those of mature neurons. These pathogenic effects were associated with VPA-mediated inhibition of the histone deacetylase (HDAC) and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) pathways, which caused transcriptional downregulation of many genes, including MARCKSL1, an actin-stabilizing protein essential for dendritic morphogenesis and synapse maturation during early neurodevelopment. Our findings identify a developmentally restricted pathogenic mechanism of VPA and establish the use of reprogrammed neurons as an effective platform for modeling teratogenic pathways.

Human pluripotent stem cells can be rapidly converted into functional neurons by ectopic expression of proneural transcription factors. Here we show that directly reprogrammed neurons, despite their rapid maturation kinetics, can model teratogenic mechanisms that specifically affect early neurodevelopment. We delineated distinct phases of in vitro maturation during reprogramming of human neurons and assessed the cellular phenotypes of valproic acid (VPA), a teratogenic drug. VPA exposure caused chronic impairment of dendritic morphology and functional properties of developing neurons, but not those of mature neurons. These pathogenic effects were associated with VPA-mediated inhibition of the histone deacetylase (HDAC) and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) pathways, which caused transcriptional downregulation of many genes, including MARCKSL1, an actin-stabilizing protein essential for dendritic morphogenesis and synapse maturation during early neurodevelopment. Our findings identify a developmentally restricted pathogenic mechanism of VPA and establish the use of reprogrammed neurons as an effective platform for modeling teratogenic pathways.

Tanabe K, Ang CE, Chanda S, Olmos VH, Haag D, Levinson DF, Südhof TC, Wernig M

Human cell models for disease based on induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells have proven to be powerful new assets for investigating disease mechanisms. New insights have been obtained studying single mutations using isogenic controls generated by gene targeting. Modeling complex, multigenetic traits using patient-derived iPS cells is much more challenging due to line-to-line variability and technical limitations of scaling to dozens or more patients. Induced neuronal (iN) cells reprogrammed directly from dermal fibroblasts or urinary epithelia could be obtained from many donors, but such donor cells are heterogeneous, show interindividual variability, and must be extensively expanded, which can introduce random mutations. Moreover, derivation of dermal fibroblasts requires invasive biopsies. Here we show that human adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells, as well as defined purified T lymphocytes, can be directly converted into fully functional iN cells, demonstrating that terminally differentiated human cells can be efficiently transdifferentiated into a distantly related lineage. T cell-derived iN cells, generated by nonintegrating gene delivery, showed stereotypical neuronal morphologies and expressed multiple pan-neuronal markers, fired action potentials, and were able to form functional synapses. These cells were stable in the absence of exogenous reprogramming factors. Small molecule addition and optimized culture systems have yielded conversion efficiencies of up to 6.2%, resulting in the generation of >50,000 iN cells from 1 mL of peripheral blood in a single step without the need for initial expansion. Thus, our method allows the generation of sufficient neurons for experimental interrogation from a defined, homogeneous, and readily accessible donor cell population.

Human cell models for disease based on induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells have proven to be powerful new assets for investigating disease mechanisms. New insights have been obtained studying single mutations using isogenic controls generated by gene targeting. Modeling complex, multigenetic traits using patient-derived iPS cells is much more challenging due to line-to-line variability and technical limitations of scaling to dozens or more patients. Induced neuronal (iN) cells reprogrammed directly from dermal fibroblasts or urinary epithelia could be obtained from many donors, but such donor cells are heterogeneous, show interindividual variability, and must be extensively expanded, which can introduce random mutations. Moreover, derivation of dermal fibroblasts requires invasive biopsies. Here we show that human adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells, as well as defined purified T lymphocytes, can be directly converted into fully functional iN cells, demonstrating that terminally differentiated human cells can be efficiently transdifferentiated into a distantly related lineage. T cell-derived iN cells, generated by nonintegrating gene delivery, showed stereotypical neuronal morphologies and expressed multiple pan-neuronal markers, fired action potentials, and were able to form functional synapses. These cells were stable in the absence of exogenous reprogramming factors. Small molecule addition and optimized culture systems have yielded conversion efficiencies of up to 6.2%, resulting in the generation of >50,000 iN cells from 1 mL of peripheral blood in a single step without the need for initial expansion. Thus, our method allows the generation of sufficient neurons for experimental interrogation from a defined, homogeneous, and readily accessible donor cell population.

Zhang Z, Marro SG, Zhang Y, Arendt KL, Patzke C, Zhou B, Fair T, Yang N, Südhof TC, Wernig M, Chen L

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is an X chromosome-linked disease leading to severe intellectual disabilities. FXS is caused by inactivation of the fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene, but how FMR1 inactivation induces FXS remains unclear. Using human neurons generated from control and FXS patient-derived induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells or from embryonic stem cells carrying conditional FMR1 mutations, we show here that loss of FMR1 function specifically abolished homeostatic synaptic plasticity without affecting basal synaptic transmission. We demonstrated that, in human neurons, homeostatic plasticity induced by synaptic silencing was mediated by retinoic acid, which regulated both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic strength. FMR1 inactivation impaired homeostatic plasticity by blocking retinoic acid-mediated regulation of synaptic strength. Repairing the genetic mutation in the FMR1 gene in an FXS patient cell line restored fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) expression and fully rescued synaptic retinoic acid signaling. Thus, our study reveals a robust functional impairment caused by FMR1 mutations that might contribute to neuronal dysfunction in FXS. In addition, our results suggest that FXS patient iPS cell-derived neurons might be useful for studying the mechanisms mediating functional abnormalities in FXS.

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is an X chromosome-linked disease leading to severe intellectual disabilities. FXS is caused by inactivation of the fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene, but how FMR1 inactivation induces FXS remains unclear. Using human neurons generated from control and FXS patient-derived induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells or from embryonic stem cells carrying conditional FMR1 mutations, we show here that loss of FMR1 function specifically abolished homeostatic synaptic plasticity without affecting basal synaptic transmission. We demonstrated that, in human neurons, homeostatic plasticity induced by synaptic silencing was mediated by retinoic acid, which regulated both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic strength. FMR1 inactivation impaired homeostatic plasticity by blocking retinoic acid-mediated regulation of synaptic strength. Repairing the genetic mutation in the FMR1 gene in an FXS patient cell line restored fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) expression and fully rescued synaptic retinoic acid signaling. Thus, our study reveals a robust functional impairment caused by FMR1 mutations that might contribute to neuronal dysfunction in FXS. In addition, our results suggest that FXS patient iPS cell-derived neurons might be useful for studying the mechanisms mediating functional abnormalities in FXS.

Mesentier-Louro LA, Dodd R, Domizi P, Nobuta H, Wernig M, Wernig G, Liao YJ

BACKGROUND: Animal models of optic nerve injury are often used to study central nervous system (CNS) degeneration and regeneration, and targeting the optic nerve is a powerful approach for axon-protective or remyelination therapy. However, the experimental delivery of drugs or cells to the optic nerve is rarely performed because injections into this structure are difficult in small animals, especially in mice. NEW METHOD: We investigated and developed methods to deliver drugs or cells to the mouse optic nerve through 3 different routes: a) intraorbital, b) through the optic foramen and c) transcranial. RESULTS: The methods targeted different parts of the mouse optic nerve: intraorbital proximal (intraorbital), intracranial middle (optic-foramen) or intracranial distal (transcranial) portion. COMPARISON WITH EXISTING METHODS: Most existing methods target the optic nerve indirectly. For instance, intravitreally delivered cells often cannot cross the inner limiting membrane to reach retinal neurons and optic nerve axons. Systemic delivery, eye drops and intraventricular injections do not always successfully target the optic nerve. Intraorbital and transcranial injections into the optic nerve or chiasm have been performed but these methods have not been well described. We approached the optic nerve with more selective and precise targeting than existing methods. CONCLUSIONS: We successfully targeted the murine optic nerve intraorbitally, through the optic foramen, and transcranially. Of all methods, the injection through the optic foramen is likely the most innovative and fastest. These methods offer additional approaches for therapeutic intervention to be used by those studying white matter damage and axonal regeneration in the CNS.

BACKGROUND: Animal models of optic nerve injury are often used to study central nervous system (CNS) degeneration and regeneration, and targeting the optic nerve is a powerful approach for axon-protective or remyelination therapy. However, the experimental delivery of drugs or cells to the optic nerve is rarely performed because injections into this structure are difficult in small animals, especially in mice. NEW METHOD: We investigated and developed methods to deliver drugs or cells to the mouse optic nerve through 3 different routes: a) intraorbital, b) through the optic foramen and c) transcranial. RESULTS: The methods targeted different parts of the mouse optic nerve: intraorbital proximal (intraorbital), intracranial middle (optic-foramen) or intracranial distal (transcranial) portion. COMPARISON WITH EXISTING METHODS: Most existing methods target the optic nerve indirectly. For instance, intravitreally delivered cells often cannot cross the inner limiting membrane to reach retinal neurons and optic nerve axons. Systemic delivery, eye drops and intraventricular injections do not always successfully target the optic nerve. Intraorbital and transcranial injections into the optic nerve or chiasm have been performed but these methods have not been well described. We approached the optic nerve with more selective and precise targeting than existing methods. CONCLUSIONS: We successfully targeted the murine optic nerve intraorbitally, through the optic foramen, and transcranially. Of all methods, the injection through the optic foramen is likely the most innovative and fastest. These methods offer additional approaches for therapeutic intervention to be used by those studying white matter damage and axonal regeneration in the CNS.

Liu Y, Yu C, Daley TP, Wang F, Cao WS, Bhate S, Lin X, Still C, Liu H, Zhao D, Wang H, Xie XS, Ding S, Wong WH, Wernig M, Qi LS

Human cell models for disease based on induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells have proven to be powerful new assets for investigating disease mechanisms. New insights have been obtained studying single mutations using isogenic controls generated by gene targeting. Modeling complex, multigenetic traits using patient-derived iPS cells is much more challenging due to line-to-line variability and technical limitations of scaling to dozens or more patients. Induced neuronal (iN) cells reprogrammed directly from dermal fibroblasts or urinary epithelia could be obtained from many donors, but such donor cells are heterogeneous, show interindividual variability, and must be extensively expanded, which can introduce random mutations. Moreover, derivation of dermal fibroblasts requires invasive biopsies. Here we show that human adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells, as well as defined purified T lymphocytes, can be directly converted into fully functional iN cells, demonstrating that terminally differentiated human cells can be efficiently transdifferentiated into a distantly related lineage. T cell-derived iN cells, generated by nonintegrating gene delivery, showed stereotypical neuronal morphologies and expressed multiple pan-neuronal markers, fired action potentials, and were able to form functional synapses. These cells were stable in the absence of exogenous reprogramming factors. Small molecule addition and optimized culture systems have yielded conversion efficiencies of up to 6.2%, resulting in the generation of >50,000 iN cells from 1 mL of peripheral blood in a single step without the need for initial expansion. Thus, our method allows the generation of sufficient neurons for experimental interrogation from a defined, homogeneous, and readily accessible donor cell population.

Human cell models for disease based on induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells have proven to be powerful new assets for investigating disease mechanisms. New insights have been obtained studying single mutations using isogenic controls generated by gene targeting. Modeling complex, multigenetic traits using patient-derived iPS cells is much more challenging due to line-to-line variability and technical limitations of scaling to dozens or more patients. Induced neuronal (iN) cells reprogrammed directly from dermal fibroblasts or urinary epithelia could be obtained from many donors, but such donor cells are heterogeneous, show interindividual variability, and must be extensively expanded, which can introduce random mutations. Moreover, derivation of dermal fibroblasts requires invasive biopsies. Here we show that human adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells, as well as defined purified T lymphocytes, can be directly converted into fully functional iN cells, demonstrating that terminally differentiated human cells can be efficiently transdifferentiated into a distantly related lineage. T cell-derived iN cells, generated by nonintegrating gene delivery, showed stereotypical neuronal morphologies and expressed multiple pan-neuronal markers, fired action potentials, and were able to form functional synapses. These cells were stable in the absence of exogenous reprogramming factors. Small molecule addition and optimized culture systems have yielded conversion efficiencies of up to 6.2%, resulting in the generation of >50,000 iN cells from 1 mL of peripheral blood in a single step without the need for initial expansion. Thus, our method allows the generation of sufficient neurons for experimental interrogation from a defined, homogeneous, and readily accessible donor cell population.

Luo C, Lee QY, Wapinski O, Castanon R, Nery JR, Mall M, Kareta MS, Cullen SM, Goodell MA, Chang HY, Wernig M, Ecker JR

BACKGROUND: Animal models of optic nerve injury are often used to study central nervous system (CNS) degeneration and regeneration, and targeting the optic nerve is a powerful approach for axon-protective or remyelination therapy. However, the experimental delivery of drugs or cells to the optic nerve is rarely performed because injections into this structure are difficult in small animals, especially in mice. NEW METHOD: We investigated and developed methods to deliver drugs or cells to the mouse optic nerve through 3 different routes: a) intraorbital, b) through the optic foramen and c) transcranial. RESULTS: The methods targeted different parts of the mouse optic nerve: intraorbital proximal (intraorbital), intracranial middle (optic-foramen) or intracranial distal (transcranial) portion. COMPARISON WITH EXISTING METHODS: Most existing methods target the optic nerve indirectly. For instance, intravitreally delivered cells often cannot cross the inner limiting membrane to reach retinal neurons and optic nerve axons. Systemic delivery, eye drops and intraventricular injections do not always successfully target the optic nerve. Intraorbital and transcranial injections into the optic nerve or chiasm have been performed but these methods have not been well described. We approached the optic nerve with more selective and precise targeting than existing methods. CONCLUSIONS: We successfully targeted the murine optic nerve intraorbitally, through the optic foramen, and transcranially. Of all methods, the injection through the optic foramen is likely the most innovative and fastest. These methods offer additional approaches for therapeutic intervention to be used by those studying white matter damage and axonal regeneration in the CNS.

BACKGROUND: Animal models of optic nerve injury are often used to study central nervous system (CNS) degeneration and regeneration, and targeting the optic nerve is a powerful approach for axon-protective or remyelination therapy. However, the experimental delivery of drugs or cells to the optic nerve is rarely performed because injections into this structure are difficult in small animals, especially in mice. NEW METHOD: We investigated and developed methods to deliver drugs or cells to the mouse optic nerve through 3 different routes: a) intraorbital, b) through the optic foramen and c) transcranial. RESULTS: The methods targeted different parts of the mouse optic nerve: intraorbital proximal (intraorbital), intracranial middle (optic-foramen) or intracranial distal (transcranial) portion. COMPARISON WITH EXISTING METHODS: Most existing methods target the optic nerve indirectly. For instance, intravitreally delivered cells often cannot cross the inner limiting membrane to reach retinal neurons and optic nerve axons. Systemic delivery, eye drops and intraventricular injections do not always successfully target the optic nerve. Intraorbital and transcranial injections into the optic nerve or chiasm have been performed but these methods have not been well described. We approached the optic nerve with more selective and precise targeting than existing methods. CONCLUSIONS: We successfully targeted the murine optic nerve intraorbitally, through the optic foramen, and transcranially. Of all methods, the injection through the optic foramen is likely the most innovative and fastest. These methods offer additional approaches for therapeutic intervention to be used by those studying white matter damage and axonal regeneration in the CNS.

Chanda S, Hale WD, Zhang B, Wernig M, Südhof TC

Neuroligins are evolutionarily conserved postsynaptic cell adhesion molecules that interact with presynaptic neurexins. Neurons express multiple neuroligin isoforms that are targeted to specific synapses, but their synaptic functions and mechanistic redundancy are not completely understood. Overexpression or RNAi-mediated knockdown of neuroligins, respectively, causes a dramatic increase or decrease in synapse density, whereas genetic deletions of neuroligins impair synapse function with only minor effects on synapse numbers, raising fundamental questions about the overall physiological role of neuroligins. Here, we have systematically analyzed the effects of conditional genetic deletions of all major neuroligin isoforms (i.e., NL1, NL2, and NL3), either individually or in combinations, in cultured mouse hippocampal and cortical neurons. We found that conditional genetic deletions of neuroligins caused no change or only a small change in synapses numbers, but strongly impaired synapse function. This impairment was isoform specific, suggesting that neuroligins are not functionally redundant. Sparse neuroligin deletions produced phenotypes comparable to those of global deletions, indicating that neuroligins function in a cell-autonomous manner. Mechanistically, neuroligin deletions decreased the synaptic levels of neurotransmitter receptors and had no effect on presynaptic release probabilities. Overexpression of neuroligin-1 in control or neuroligin-deficient neurons increased synaptic transmission and synapse density but not spine numbers, suggesting that these effects reflect a gain-of-function mechanism; whereas overexpression of neuroligin-3, which, like neuroligin-1 is also targeted to excitatory synapses, had no comparable effect. Our data demonstrate that neuroligins are required for the physiological organization of neurotransmitter receptors in postsynaptic specializations and suggest that they do not play a major role in synapse formation.SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Human neuroligin genes have been associated with autism, but the cellular functions of different neuroligins and their molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Here, we performed comparative analyses in cultured mouse neurons of all major neuroligin isoforms, either individually or in combinations, using conditional knockouts. We found that neuroligin deletions did not affect synapse numbers but differentially impaired excitatory or inhibitory synaptic functions in an isoform-specific manner. These impairments were due, at least in part, to a decrease in synaptic distribution of neurotransmitter receptors upon deletion of neuroligins. Conversely, the overexpression of neuroligin-1 increased synapse numbers but not spine numbers. Our results suggest that various neuroligin isoforms perform unique postsynaptic functions in organizing synapses but are not essential for synapse formation or maintenance.